Nirvana’s Nevermind, the album that changed everything, turns 20 years old on Saturday, no doubt inducing a thorough, nostalgic rehash of the impact Nirvana had on the record industry, and the culture at large. Nirvana has been celebrated, rightly, for giving voice to the freaks and the weirdos, for opening up a lot of kids stranded in the suburbs to the idea that there’s something more to life than this, and for very briefly creating a path for the counterculture to enter the mainstream (a path that had already fallen into tatters when Kurt Cobain killed himself in 1994.) One aspect of their brief reign that has been somewhat forgotten, however, is how strongly the band broke with the sexist norms of the era, choosing instead a pro-feminist public stance and song lyrics. Feminist fans never forgot, however. After canvassing for interviews online with women who identified as both feminist and as Nirvana fans, I discovered that the group’s aggressive questioning of gender roles may have had as long-lasting an impact as the invention of “alternative rock” radio, and that influence has remained good and pure even as the era of rock dominance comes quietly to a close.

Nirvana’s opening salvo in its assault on mainstream rock, “Smells Like Teen Spirit,” did more than just wash away any musical relevance of bands like Poison and Winger, but it also laid waste to the sexism that fueled so much hair metal and other dude-centric hard rock. The first human faces you see in the video for “Smells Like Teen Spirit” belong not to the band members, but to a group of heavily tattooed women dressed like anarchist cheerleaders, a swift but brutal rebuttal to all the images of acceptable femininity that your average suburban teenager lived with at the time. Forget the hair metal groupies or the bubbly beauty queen cheerleaders. For girls watching this video, it was a revelation: You could instead choose to be a badass.

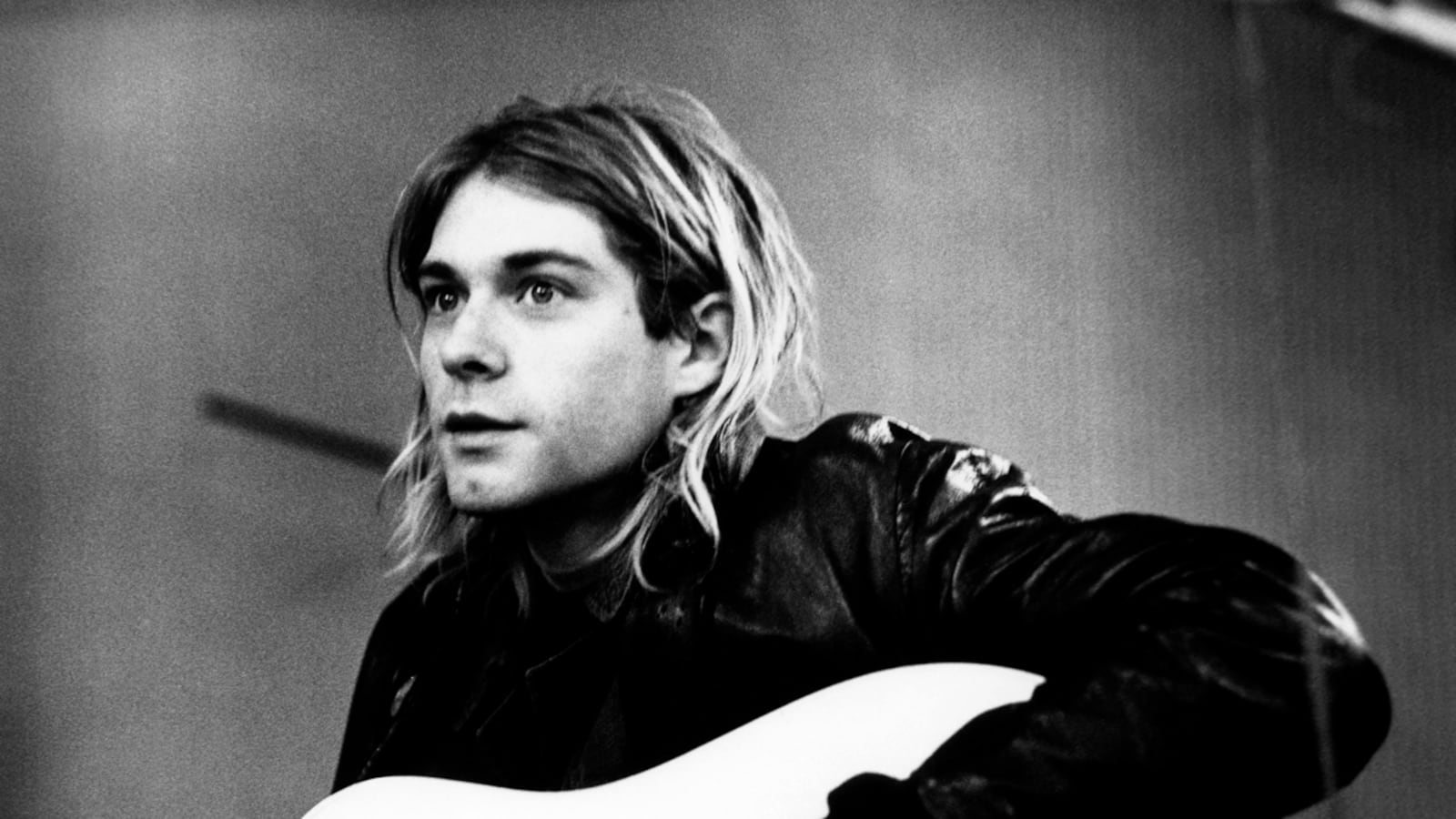

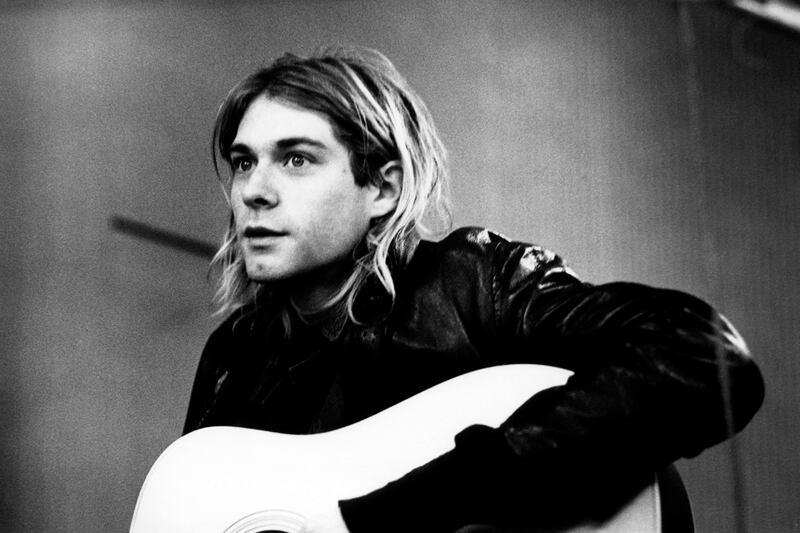

The cheerleaders were just a taste of what Kurt Cobain had up his sleeve when it came to subverting traditional gender roles. It wasn’t just the kick-ass women in this one video. Nirvana baked feminist ideas right into their lyrics and image. Nirvana had songs like “Polly," “Pennyroyal Tea,” and “Breed,” which dealt directly with gender issues from a pro-feminist perspective, and songs like “About a Girl” and “All Apologies,” which employed a layered, nuanced understanding of love and gender. Alison, 31, who reached out through Twitter, marveled at the gap between Nirvana and the bands like Warrant that came before it, saying, “So much of the music made by men at the time that was popular was all about how women were basically just holes to fuck,” adding that Cobain, “felt like a guy who viewed women as people.”

“He was ironic,” said Jo, a 29-year-old resident of London, citing Cobain-penned songs like “Rape Me” and “Polly” as ones that spoke of feminism powerfully, if sideways, “and he played around with gender roles, which I loved. There was an androgyny about him that was very refreshing.” Many of the women interviewed initially found “Rape Me” an unsettling song, but eventually came around to seeing it as Cobain’s clumsy but well-intentioned attempt to incorporate feminist theory into his worldview. It’s one of the few songs in all of rock history to acknowledge rape as a crime of power and violation, instead of excessive sexual desire. Many feminists object to using rape as a metaphor this way, but what was undeniable was Cobain’s extreme hostility to the possessive mentality that leads to rape.

Female fans detected a humanistic view of women in the lyrics and certainly in Cobain’s public pro-feminist persona. Cobain was an early advocate of Sassy magazine, the late '80s through mid-'90s magazine aimed at teenage girls that had a definite feminist bent. He also enjoyed provoking and mocking American gender anxieties, engaging in previously unheard of behavior in a major rock star—glam rock aside—such as wearing women’s clothes and making out with male bandmates in public, just daring people to have a problem with it. “I really picked up on the sensitivity and girl-positive nature of Nirvana,” explained Kate, a 30-year-old from Toronto, “it was important to me to see a famous, attractive man share some ideas about feminism with me and be unapologetic and forthright about it.”

Nirvana’s feminism stemmed directly from the Northwest rock scene that birthed the band. Even though they were associated with Seattle, NPR’s music critic Ann Powers noted, “They came out of Olympia, a much different scene, more female-dominated.” Riot grrrl—a subgenre of punk rock that focused on empowering girls to speak out on feminist topics such as reproductive rights and sexual violence—sprang from the same circles as Nirvana, and Cobain made friends with famous riot grrrls Tobi Vail and Kathleen Hanna, who inadvertently gave Cobain the title idea for "Smells Like Teen Spirit.” “From the very beginning, he was aware of the gender issue,” Powers said, arguing that the riot grrrls “were important to him.” Fans of both Nirvana and riot grrrl agree. Kate described Nirvana as “a riot grrrl band, basically.” Tara, who was living in Alabama when she discovered Nirvana, particularly admired the riot grrrl connection, saying, “The thing I really loved about that was it didn’t seem like a stunt. They ran with the riot grrrl crowd out of genuine admiration for them and what they stood for.”

Even outside of the self-proclaimed riot grrrl world, feminism left its mark on the underground rock scene that Nirvana turned mainstream. Powers said, “In the '90s, there was a lot of focus on feminism in the rock scene.” As examples, Powers pointed to L7’s snottily funny pro-woman lyrics, the founding of Rock for Choice, and the Northwest scene’s heavy anti-violence activism in the wake of the rape and murder of Mia Zapata, the lead singer of the beloved Seattle-based Gits.

For fans, Nirvana often proved a gateway drug to discovering music that had female musicians to go right along with the feminist sentiments. Tara cited Nirvana as the reason she fell hard for alternative rock, bringing her to Tori Amos, Liz Phair, Hole, and Babes in Toyland. Mickey, a Seattle native, was already a fan of many female-led punk bands, but felt Nirvana broadened her horizons. “I probably became aware of bands like L7, Sleater-Kinney, and of course, Hole, through my love of Nirvana.” Alison, who described herself as growing up in a “basic, bland suburb,” also discovered L7, Hole, and Bikini Kill through Nirvana, but felt that loving Nirvana primed you to listen to feminist musicians outside of their direct sphere of influence. She suggested that the pride Nirvana gave to outcasts and weirdos “eventually led to a more specific validation that being a woman was fine, too,” adding that this shot of feminist pride “made me more inclined to seek out strong women in areas like music, literature, etc.”

The brief moment when the most famous rock band on the planet was a girl-loving, feminism-promoting train of subversion only lasted, really, for three years. We didn’t know it at the time, but Cobain’s suicide marked the beginning of rock’s slow decline, as it splintered into ever-more-twee indie rock of the She and Him, Bright Eyes, and Fleet Foxes variety, and into tediously macho heavy metal-influenced forms like Godsmack, A Perfect Circle, and Slipknot, giving hip-hop the chance to take rock’s place as the dominant pop music of our era. The fault lines had already started forming in Cobain’s lifetime, but there’s a strong reason to believe his loss accelerated the inevitable. This fracturing was kicked off by an all-out gender war as anti-feminist young men started aggressively reconquering hard rock. “It’s arguable,” said Powers, “that what made rock irrelevant is the re-entrenchment of rock in masculinity.” The infamous Woodstock ’99, which devolved into horror, symbolized this re-entrenchment, not only because of the violence and the rapes enacted by this new generation of young men who rejected Cobain’s egalitarian philosophy, but also by a stage dominated by “no girls allowed”-style bands like Metallica, Kid Rock, and of course, Limp Bizkit.

Late '90s rock burned itself out, but from the ashes rose what we now call indie rock, and while its impact has been dramatically muted compared to the alternative rock juggernaut of the '90s, grunge-era feminism left its mark. A generation of women grew up clutching Nirvana records and moved on to clutch guitars—or otherwise see themselves as musicians instead of just fans—fulfilling the Northwest rock scene’s feminist vision, a vision that moved mainstream because of Nirvana’s popularity. Women now dominate mainstream pop in a way they didn’t in the '90s, resulting in megastar acts like Lady Gaga and Amy Winehouse, who are (or could have been) the brains as well as the face of their operations. In many ways, this normalization of feminism in rock represents the most lasting impact of the great alternative rock revolution Nirvana unwittingly kicked off 20 years ago with the release of Nevermind. Flannel shirts and combat boots may never be pulled out of the closet in the world of indie rock that was birthed from alternative rock, but the idea that rock music can and should embody feminist ideals lives on in artists as diverse as Neko Case, the Vivian Girls, and the Gossip.