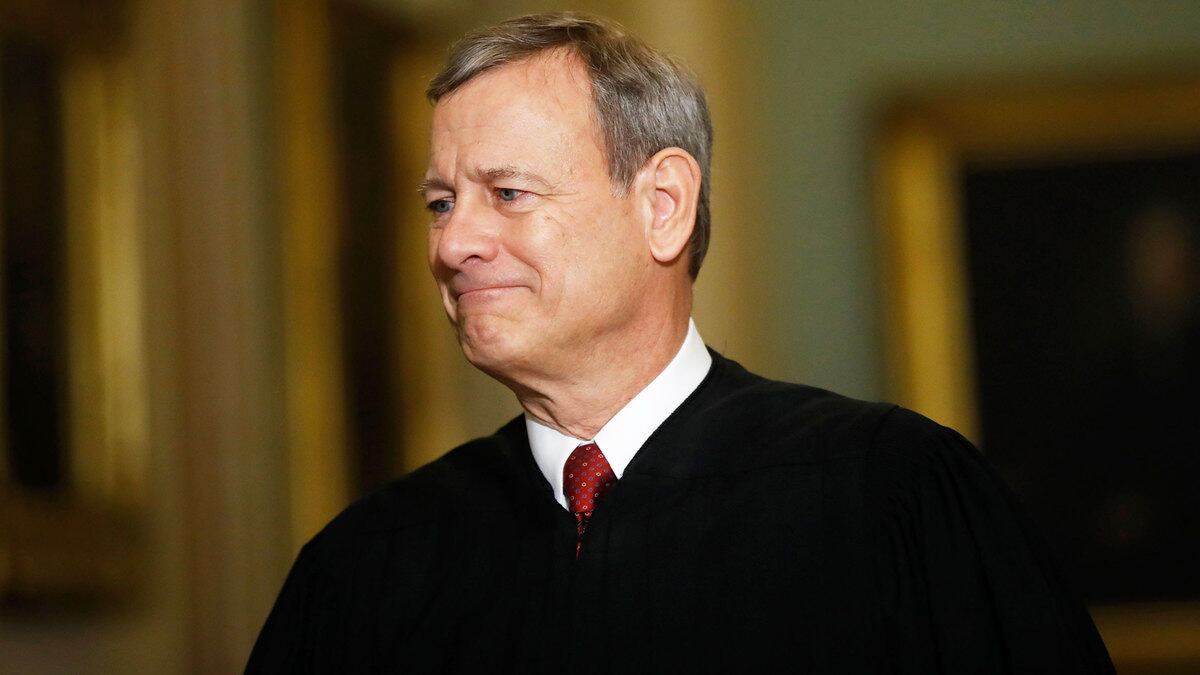

Is John Roberts the savior of liberalism?

In the last seven days, the Chief Justice, who was nominated by President George W. Bush, has voted to strike down Louisiana’s restrictions on abortion clinics, preserve DACA (the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals) program, and protect LGBTQ Americans from being fired for being gay or trans.

So is JGR the new RBG?

Not so fast.

First, let’s remember, Roberts has voted for conservative outcomes at least as often: on Trump’s “travel ban,” on voting rights, on unions, on the First Amendment, and a host of other issues.

And while in each of this past week’s cases the Chief Justice was the swing vote that led to liberal results, he voted the way he did for fundamentally conservative reasons.

Most recently, in the abortion case, June Medical Services v. Russo, Roberts did not join the core argument of the four liberals. On the contrary, he began his opinion by stating that Whole Woman’s Health v. Hellerstadt, the precedent that Justice Stephen Breyer’s plurality opinion relied on, was “wrongly decided” (Whole Woman’s Health, on which Anthony Kennedy joined the four liberals, invalidated Texas’s requirement that abortion providers have admitting privileges at a hospital because it placed an undue burden on women seeking abortions.)

But, he said, the question is not whether that precedent “was right or wrong, but whether to adhere to it in deciding the present case.”

Since the laws were almost identical–Louisiana’s restrictions on abortion providers were almost the same as Texas’s restrictions in Whole Woman’s Health –Roberts concurred in the judgment and invalidated the laws.

This wasn’t a ruling for abortion rights; it was a ruling for stare decisis, the principle that the Supreme Court must respect its own precedent. That is a principle that may lead to conservative or liberal outcomes, depending on the case, but it is fundamentally a judicially conservative value.

Similarly, in the DACA case, Department of Homeland Security v. Regents of the University of California et al., Roberts did not praise DACA; he only held that, in repealing it without taking into account the 700,000 people who relied upon it, the Trump administration was “arbitrary and capricious,” in violation of the Administrative Procedure Act.

Roberts thus left open the possibility that a future DACA repeal could be valid, if the repeal process followed the law and took all of the relevant factors into account. Indeed, he rejected the plaintiffs’ constitutional claims entirely. Once again, his opinion was less about the underlying values at stake and more about the court’s role in preserving the rule of law.

In the LGBTQ case, Bostock v. Clayton County, Roberts did not write an opinion, but the one he joined, written by fellow conservative Justice Neil Gorsuch, was a highly textualist one, sticking to the “words of the law on the page,” as conservatives frequently like to say.

Ironically, that principle has often been interpreted as a kind of code. For decades, Republicans have complained about “activist judges” who make law instead of interpreting it. After all, there’s no explicit right to abortion in the Constitution, to take the most famous example. Stick to the words on the page, they say.

But in Bostock, that exact principle led to a liberal policy result. Firing someone for being gay or trans is discrimination “because of sex,” since it’s punishing someone for behavior that would be perfectly acceptable had they been of the opposite sex.

In other words, in all three of these recent cases, Roberts has voted for liberal outcomes because of conservative jurisprudence. Ideological conservatives vote for conservative results (as, for example, Justice Brett Kavanaugh did in June Medical, defying Senator Susan Collins’s absurd prediction that he wouldn’t). Judicial conservatives vote for conservative jurisprudential values, even if the policy results will be liberal.

Nor is this the first time Roberts has done this.

Most famously, Roberts twice preserved the Affordable Care Act. Once again, though, he did so for conservative reasons: In the 2017 challenge, for example, he interpreted the phrase “established by the state” according to longstanding jurisprudential standards that laws are meant to function, not self-destruct.

And last year, the Chief Justice wrote an unusual opinion that at first defended the Trump administration’s proposal to ask about citizenship on the census, only to invalidate it because the administration lied, over and over, in its reasons for doing so. The law “calls for an explanation for agency action,” Roberts wrote in the opinion for the Court. “What was provided here was more of a distraction.”

As he did in June Medical, the Chief Justice sided with the conservative underlying values but voted the “liberal” way because of the rule of law.

That same term, Chief Justice Roberts voted with the Court’s four liberals on an important administrative law case, preserving deference to agency interpretations of law. The stakes were high: The regulatory state as we know it depends on agencies being able to interpret the laws they have to enforce. And conservatives had mounted a significant effort to overturn the Court’s precedent on the matter.

But Roberts joined an opinion, written by Justice Elena Kagan, that focused on stare decisis and respect for precedent.

At the time, I wrote, “If this approach to stare decisis… is applied to the long line of cases beginning with Roe v. Wade, it would lead to upholding the right to abortion. Imagine how angry conservatives will be with Chief Justice Roberts then.”

Well, imagine no more.