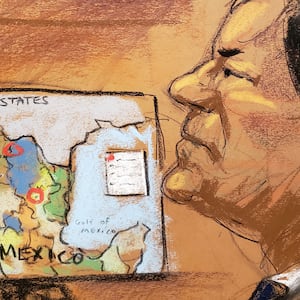

Joaquin “El Chapo” Guzman, the Mexican drug cartel leader accused of sending a half-million pounds of cocaine into the U.S. over 30 years, was found guilty in Brooklyn federal court on Tuesday.

Guzman, 61, faces a mandatory sentence of life behind bars in the U.S. after two escapes from prison in Mexico. “It is a sentence from which there is no escape and no return,” said U.S. Attorney Richard Donoghue following the verdict. Guzman’s attorney said they plan to appeal.

Jurors convicted Guzman on all 10 counts brought by federal prosecutors after six days of deliberations. They entered the courtroom just past noon on Tuesday looking somber but unafraid of passing judgement on one of the world’s most dangerous men.

After the verdict was read, Guzman waved to his wife, Emma Coronel Aispuro, who winked at him but did not shed a tear.

Prosecutors charged him in a conspiracy as head of the Sinaloa cartel, which they described as “the largest drug-trafficking organization in the world.” His three-month trial detailed the ruthless business of running the cartel.

“Money. Cash. Murder,” Assistant U.S. Attorney Adam Fels said to the jury in his opening statement. “A vast global narcotics trafficking empire—that’s what this case is about, and what the evidence will show.”

So expansive was Guzman’s empire that a mere four shipments could provide “more than a line of cocaine for every single person in the United State,” Fels also claimed.

The illicit proceeds afforded Guzman a flashy, luxe life, prosecutors charged.

“Who has a zoo with little trains? Who flies around in jets and helicopters? Who has diamond encrusted pistols? Who lives in the mountain tops and has his food flown to him?” Assistant U.S. Attorney Andrea Goldbarg told jurors during her closing arguments.

“The answer is common sense: a boss of the Sinaloa Cartel does this,” she reportedly said.

People who got in Guzman’s way, be they witnesses or uncorrupted government officials, would be killed off, often with assassins known as “sicarios,” prosecutors claimed.

A witness also testified that Guzman himself carried out multiple executions. In one case, Guzman allegedly beat two rivals with a stick and then threw their “ragged doll” bodies toward the foot of a fire—before shooting them both in the head, according to reports.

“He was a hands-on leader,” Fels also said.

Jesus Zambada Garcia, the brother of Guzman’s purported partner-in-crime, revealed how the cartel’s structure was rather corporate.

Zambada told jurors that he joined up with the cartel in 1997 and set up an accounting system. Between 1998 and 2008, Zambada ran three warehouses in Mexico City, or “bodegas,” as he called them in Spanish. These “bodegas” were used to move coke into the United States. During Zambada’s decade at the helm of this Mexico City operation, some 80 to 100 tons of coke were transported from his “bodegas” across the border every year, he said.

A management hierarchy was also key to the Sinaloa organization. Guzman and Ismael “El Mayo” Zambada reigned supreme. Below them were sub-leaders such as Zambada, who ran distribution centers, followed by sicarios. And corrupt government officials made it all possible, Zambada said.

Guzman’s defense team, led by high-profile lawyer Jeffrey Lichtman, seized on corruption in Mexico, portraying him as a scapegoat for “El Mayo.”

Despite indictment and a $5 million bounty on his head, El Mayo has somehow managed to evade capture, Lichtman told jurors.

“He bribed the entire government of Mexico—including the current president of Mexico,” Lichtman claimed, arguing “the current and former president of Mexico received hundreds of millions in bribes from Mayo...”

Mexico’s president from 2006 to 2012, Felipe Calderon, denied the allegations on Twitter shortly thereafter.

Judge Cogan told the jury to ignore Lichtman's allegations of shady backroom dealing, telling the that prosecutors’ motives in bringing a case against Guzman didn't matter.

Guzman’s associate reportedly testified at a later time, however, that he gave former Mexican President Enrique Pena Nieto an $100 million payoff.

Meanwhile, Guzman’s many alleged attempts to evade justice—he escaped prison in 2001 via laundry cart and then again in 2015 via tunnel—made the narrative even more gripping. (In a testament to the made-for-TV nature of the case, Alejandro Edda, who plays Guzman on the Netflix drama Narcos, came to observe him in court.)

Lucero Guadalupe Sanchez Lopez, who claimed to have been Guzman’s lover, told the jury about one of Guzman’s dramatic escapes, from early 2014.

She and Guzman were in bed when they woke to his secretary, Condor.

“Wake up! They’re on us!” she recalled Condor warning at about 4 a.m.

Condor and Guzman bolted into the bathroom and called for Sanchez. The men lifted a lid off the bathtub with a “piston” like mechanism, revealing a set of stairs that ultimately led to a tunnel.

“He went off first, he left us behind,” Sanchez recalled of Guzman. “He was naked.”

Guzman was tracked down not long after at the Hotel Miramar, in Mazatlan. After a days-long manhunt upon receiving cartel intel, DEA agent Victor Vazquez and a team of Mexican Marines closed in on the hotel. After his team swept the hotel, they brought Guzman to a garage. He was on his knees.

Guzman would break out of prison again the next year. When Guzman was recaptured again in 2016, however, it stuck.

His subsequent extradition led to the marathon trial and Tuesday’s verdict.