On January 26, 2020, Kobe Bryant was killed in a helicopter accident along with his daughter, Gianna. He was 41 years old. The following remembrance was written in 2015, just after he announced his retirement from basketball.

I don’t think I’ve ever seen Kobe Bryant scared.

That reads less impressive than it should, so let me try again: I don’t think I’ve ever seen Kobe Bryant show the capacity for fear.

It’s a given that professional athletes are confident, with a small percentage of them diabolically so. Bryant had that—and still has that, apparently, even as his failing body forced him on Sunday to announce that he’ll retire at the end of this season. But Bryant has something more, something that, in 15 years of covering the NBA, and in many more as a fan, I’m not sure I’ve seen in anyone else.

I have a lot of Kobe Bryant memories, and nearly every one of them reflects on a guy pathologically certain of himself. This has not always been a strength, of course, a fact of which there’s no better or more relevant reminder than this belated decision to retire. He shouldn’t have gone past last season, and it wouldn’t have been a terrible idea to quit the game a year or two earlier. But he didn’t, because guys like him rarely leave until they feel they have no other choice. A lot of them drag it out because they’re afraid of what comes next.

With Bryant, I don’t think fear is in play.

Some of it must be genetic, but I’m certain his upbringing played a role. My long-held Kobe theory is that he never really knew where he fit. He spent much of his childhood in Italy, a black American kid who, at least culturally, was never fully comfortable in either place. Both in Italy and on his adolescent return to the States, he spoke the language, but it always seemed forced. Think of how scary that would be—for most kids. Kobe thrived regardless. He took an R&B star to the prom, and he took his talents to the NBA.

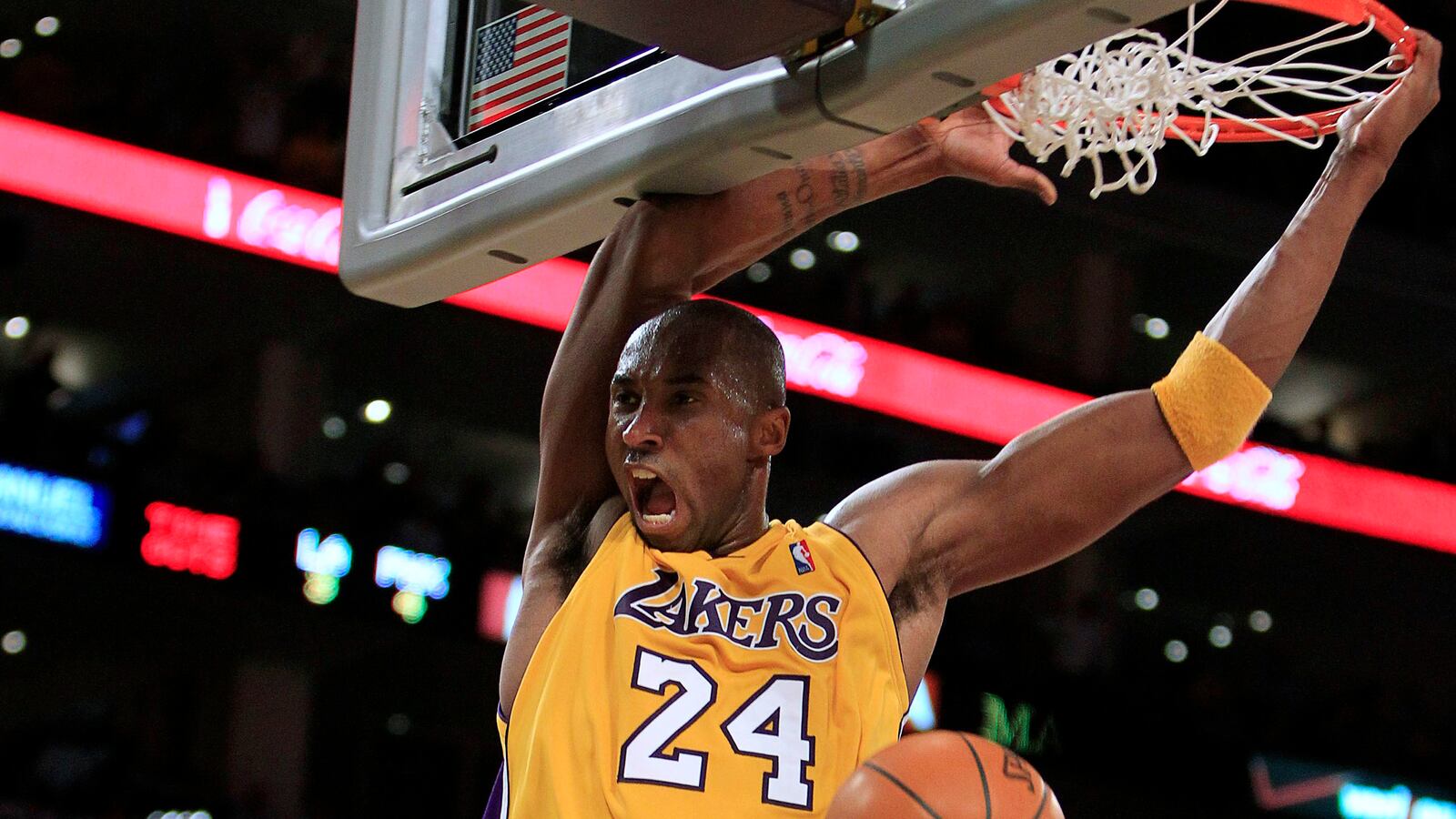

In the pros, he was instantly dazzling, an unpolished, errant-shooting project whose insistence on his own destiny allowed him to overcome the very failings his fearlessness inspired. Even then, he never feared taking a shot, any shot. It brought him critics, including his biggest and most prominent teammate. He ran from none of them.

In the fall of ’99, I started at SLAM, the monthly basketball magazine, just as Kobe was beginning the season that would bring his first NBA title, and the first of three straight for his Lakers. Of course, the question of whose Lakers they really were—his, or Shaquille O’Neal’s—meant that even those triumphant years were full of turmoil. Kobe became the most popular player in the game, and also the most hated. He was aloof as a teammate. He brawled with opponents. Young fans thought him a fraud, the guy with the upper-class European upbringing who aped Michael Jordan and faked his place in basketball’s hip-hop era. He paid lip service to maturing, but he never actually changed, because why change unless you’re afraid of the consequences of staying the same?

But then he changed in 2003, of course. Everything did. The rape allegation and ensuing media circus altered him and the world’s perceptions. If he was ever scared, it was then, but somehow his clenched-jaw apology came across more as anger—at himself, for letting his confidence turn to hubris, and for jeopardizing his destiny. He returned with a harder edge, tattoos, and fewer smiles and more m’fing with the media. He was changed now, for sure.

But fear? Nah. Fear doesn’t come back and average a league-best and career-high 35 points two years later. Fear doesn’t switch from Adidas to Nike, even after the Swoosh has made it clear that some lanky 18-year-old from Akron, Ohio, is their future, and outdo LeBron both in shoe sales and championships. Fear doesn’t hold a snake to his cheek for a magazine cover, as he did for our photographer late one night in a Manhattan studio. And fear sure as hell doesn’t chase Shaq out of town and stick around in the certainty that he’ll find a supporting cast to win with, on his own terms—and then do it, twice in a row.

The definitive, literal encapsulation of all this came in 2010, during a game against the Orlando Magic, when noted NBA knucklehead Matt Barnes stood on the baseline and faked an inbounds pass at Kobe Bryant’s face, not two feet away. It remains one of the most fascinating wordless exchanges you’ll ever see: Barnes pumps the ball so close to Bryant’s nose, he might have grazed it. And Kobe, popping gum, bobbing from right foot to left and back again, doesn’t react. He doesn’t flinch. He doesn’t so much as blink.

Kobe Bryant will go down as one of the 10 best players in NBA history, easy, and he’s in a lot of people’s top five. But I don’t think any objective fan over the age of 30 can put him at No. 1, because that means putting him ahead of Jordan, and that just seems impossible. The numbers are close, but not quite there. The five championship rings are close, as well, but for three of those he wasn’t clearly the best player on his own team. He never could surpass the player on whom he based his entire game.

But here’s the thing: He got really fucking close. Trying to be like Mike made perfect sense for an 18-year-old kid entering the NBA in 1996, but trying to make a career of it was insanity. And yet Kobe did just that, in spite of the fans who mocked him for “copying” a legend’s game, and in spite of the near certainty that he could ever actually be better than the original. He did it, and he nearly pulled it off. Anyone else would have been afraid to try.