If you have a paper thin skin (as I do) and are paid to comment on the news (this, for some mysterious reason, also applies to me), it’s advisable to fully disengage from writing about the Edward Snowden saga. After the initial leaks, I offered a cautious piece, urging against the instant beatification of the former NSA contractor. We knew little about him, I argued, so let’s wait for it to play out, and we’ll be better situated to determine if he was more Pentagon Papers than Pumpkin Papers. But it's one of those stories allergic to nuance: you're either a lackey of empire (the Snowden skeptic) or a fulminating anti-American trying to undermine Obama’s foreign policy (the Snowden supporter). In a debate without shades of grey, I'd rather leave the whole business to those with more anger, passion, and energy.

But allow me to wade into one tiny aspect of the Snowden affair without wading into the debate: across Twitter and cluttering my inbox; in stories from Time, Bloomberg, The Verge, The Guardian, The Washington Post, Reuters, and dozens of others; and in breathless dispatches from the universe of Facebook, I have been repeatedly informed within that last twenty-four hours that Edward Snowden has been “nominated for a Nobel Peace Prize.” Take that previous Nobel Peace Prize laureate Barack Obama!

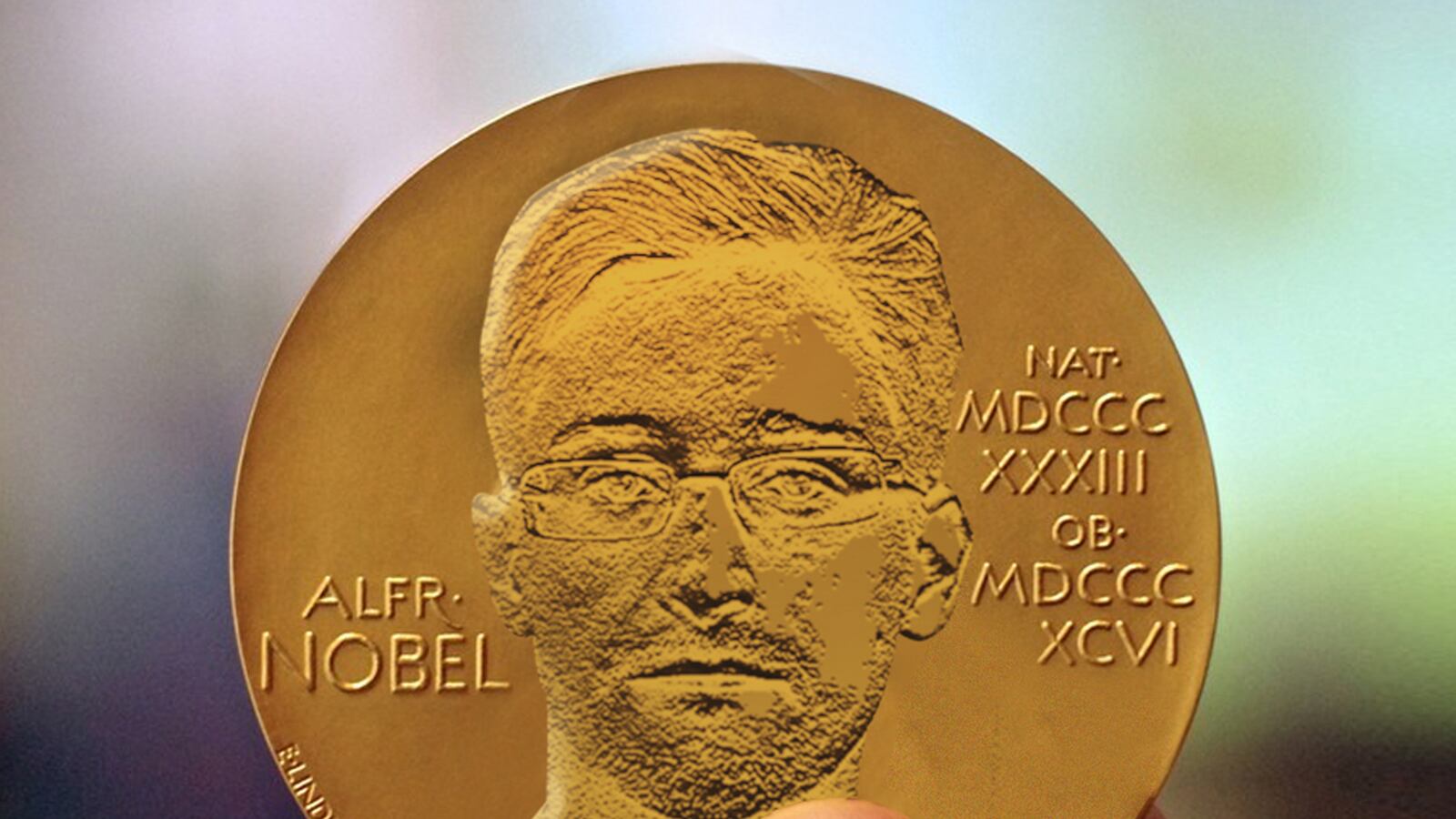

Well, almost. Because all of the media outlets listed above, and all my Snowdenite friends on Facebook and Twitter, have fallen for the perennial person whose politics I share was nominated for the most meaningless prize on the planet story. But what, dear reader, does it actually mean to be nominated for a Nobel Peace Prize? The short answer: not much.

Remember that flurry of reports in October that “Russian President Vladimir Putin was nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize by an advocacy group that credits him with bringing about a peaceful resolution to the Syrian-U.S. dispute over chemical weapons?” In 2012, hundreds of news organizations reported on Bradley Manning’s nomination (one of those Norwegian parliamentarians who nominated Snowden also nominated Manning). In 2011, the wires were clogged with stories of a potential Peace Prize gong for Julian Assange. And my personal favorite, courtesy of a former Swedish deputy prime minister and parliamentarian, the 2006 nominations of former U.N. ambassador John Bolton and right-wing polemicist Kenneth Timmerman, author of books on Jesse Jackson, the Iran nuclear program, and how the French “betrayed” America. (On the cover of Timmerman’s book Countdown to Crisis: The Coming Nuclear Showdown with Iran, potential readers are told the book is written by “a Nobel Peace Prize nominee.”)

And one can have a bit of fun mining the online database that catalogues nominations, though only those submitted between 1901 and 1956. A sample of the brilliant suggestions by not-so-brilliant nominators: In 1939, twelve forward-thinking members of Swedish parliament put forth the name of gullible “peacemaker” Neville Chamberlain. A handful of months later, Luftwaffe planes would be swooping across the Polish countryside, dropping bombs on retreating kulaks, and dismembering Europe. In 1948, a Czech professor named Wladislav Rieger nominated his new overlord, Soviet sadist Josef Stalin, presumably in hopes of getting a new pair of boots and an extra ration of gulasch. Former Norwegian foreign minister Halvdan Koht beat him to it, though, nominating Uncle Joe in 1945 for his efforts in defeating the fascist power it was previously allied with.

Journalists are a hungry species, constantly looking to satiate their appetite for clickable, if not necessary newsworthy, stories. And most journalists are aware that the pool of people qualified to “nominate” for the peace prize is so absurdly wide as to make stories of nominations pointless. Let’s crib from the Associated Press’s recent precis on just who can nominate: “[Nominators] include former laureates; current and former members of the committee and their staff; members of national governments and legislatures; university professors of law, theology, social sciences, history and philosophy; leaders of peace research and foreign affairs institutes; and members of international courts of law.” And if you are aware of a nomination like Snowden, that information almost certainly comes from a nominator attempting to create a news story—because all submissions are kept secret by the committee for fifty years.

So yes, any member of a “national government or legislature” or, say, any philosophy professor—from a member of Hungarian parliament representing the neo-Nazi Jobbik party to the bonkers Slovenian professor Slavoj Žižek—can create fake news by legitimately nominating someone who might be considered illegitimate by reasonable people.

This year, it was two predictable and bog-standard Norwegian lefties named Baard Vegar Solhjell and Snorre Valen, both members of parliament from the Socialist Left (SV) party, who nominated Snowden. Incidentally, Solhjell and Valen represent the seventh largest party in the tiny Nordic country, which managed a paltry 4 percent of the vote in the last parliamentary elections. So who cares that two random Norwegian radicals are fans of Edward Snowden and not particularly fond of the Obama administration's foreign policy? Apparently everyone in the American media.

And here I am, 8 years later, still waiting for Peace Prize nominee John Bolton to finally get that call from Oslo...