Pakistan is a bulwark against extremism, we’re told, even as Pakistani assassinations, abductions, and suicide bombings make the news with numbing regularity. It’s a key ally and the recipient of billions of U.S. aid, and yet the SEAL raid on Osama bin Laden’s Abbottabad compound had to be mounted like a mission behind enemy lines.

Fiction writers, better than politicians or pundits, make satisfying work out of such contradictions. Conflict, irony, complication—these things are narrative fuel, and a good paradox can put a novel into the pantheon (c.f. Catch 22). So no wonder contemporary Pakistan, somehow both friend and foe, increasingly modern and stubbornly feudal, has provided a resonant setting for novels and short stories in recent years. Ali Sethi’s The Wish Maker, Mohsin Hamid’s The Reluctant Fundamentalist, and Daniyal Mueenuddin’s In Other Rooms, Other Wonders have been the best to cross my desk, with Mueenuddin’s graceful volume, a collection of stories set in rural Pakistan, at the top of the heap.

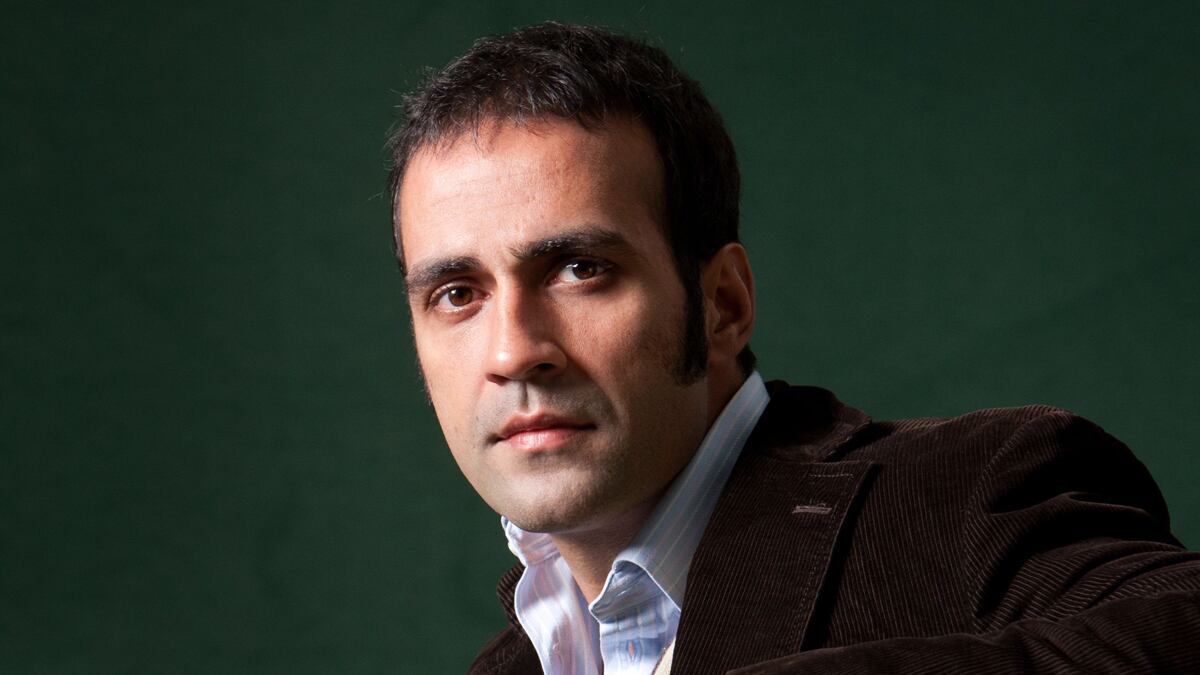

Now, however, I have a new favorite (partially) Pakistan-set book of fiction to recommend: Noon, a meditative, occasionally jolting novel by Aatish Taseer, the 31-year-old son of the former governor of Punjab, Salman Taseer. In January the elder Taseer, a secular politician and an outspoken critic of the country’s retrograde blasphemy laws, was gunned down in Islamabad by his own bodyguard—an assassination that made headlines here and was widely condoned, even celebrated, by Pakistani clerics.

ADVERTISEMENT

Father and son were estranged at the time of the killing. The young author had published several pieces of journalism and a 2009 memoir, Stranger to History: A Son’s Journey Through Islamic Lands, that were highly critical of Pakistan. These had angered his patriotic father. Even more complex was their history: Aatish is the product of Salman Taseer’s relationship with an Indian journalist, and Aatish’s Indian matrilineal roots made it difficult for his father to acknowledge him publicly. They didn’t even meet until the author was 21 and weren’t on speaking terms when he was killed.

Knowing something of that backstory enriches the semi-autobiographical Noon, a deeply unsentimental novel about a young man with an Indian mother and a shadowy, powerful Pakistani father. As Rehan Tabassum progresses in and out of circles of privilege—an aristocratic Delhi household, a private college in Massachusetts (Aatish went to Amherst), and a telecom empire in Port bin Qasim, Pakistan—he never feels entirely at home, and his interloper’s unease gives the novel a clarity of vision; by standing at a distance Tabassum achieves bracing focus.

This is evident in a stray, vivid description—a view of the Pakistani countryside from a moving train, “the darkened landscape, dotted here and there with a well or granary bathed in fitful tube light” or of Delhi, glimpsed by a young Tabassum, from his mother’s car: “They passed a blue ice-cream cart on the side of the road. A man with an open shirt and a small, bird-like chest lay asleep on its cool aluminum surface.”

More frequently Tabassum turns that acuity inward, drawing lines of complicity between, say, the moral failings of the Delhi police force and his own aristocratic detachment. In the long, increasingly discomfiting middle episode, which follows a Kafka-esque investigation into stolen jewelry at his mother’s house, the college-aged Tabassum is brought up again and again by his entitlement and passive cruelty. The police turn to torture—with Tabassum’s instinctive blessing. “I felt myself a rougher man than I knew,” he narrates. “I wanted the servants quickly to know how ruthless I could be.”

The New India is shown to be corrupt and merciless—a melancholy, casually violent place—but Pakistan and specifically the town of Port bin Qasim, near Karachi, is a kind of dark wonderland, drawing Tabassum irresistibly to it, even as he finds the country to be threatening and perverse. The final section of the novel is set there, during the spring of 2011.

Tabassum travels to Pakistan to see his father, who runs a telecom and broadband Internet company, but he tarries in Port bin Qasim with his playboy half-brother Isffy, a black sheep in the family. Isffy likes to videotape women he has sex with—especially his father’s mistresses—but one of these tapes has fallen into the wrong hands and he is being blackmailed. He suspects his uncle Narses, and aims to expose his affair with a younger man. Playing backdrop to all this intrigue—the preoccupations of an elite family—is the roiling city itself, a seaside town with an underclass of Islamic fundamentalist protesters, violently anti-Western but unpredictable too: “They planted bombs at each other’s meetings; they rioted at the slightest provocation; they dug themselves into the breeze-block ghettos that stretched for miles along the periphery of the city.”

Isffy’s blackmail plotline provides the novel with its brutal climax—and deepens the perception that Pakistan is both decadent and abnegating, irrevocably Westernized and violently closed off. The novel’s smart coda, a series of Internet postings about Isffy’s affair that Tabassum reads in London, does nothing to reconcile or rationalize these contradictions. No sense trying to do so, seems to be the message of this intelligent, unsettling novel—a theme only a fiction writer could express in such a satisfactory way.