Based on promotional materials alone, it seems safe to assume that no one walked into Jordan Peele’s Nope with “rampaging chimpanzee” on their Bingo cards. And yet…

Peele’s stunning summer blockbuster celebrates the science fiction genre while also forcing its viewers to confront, as the director put it in a recent interview, our shared addiction to spectacle. Daniel Kaluuya plays OJ Haywood, a quiet but observant horse trainer who’s struggling alongside his sister, Emerald (a magnificent Keke Palmer), to save their family’s horse ranch from financial devastation. Steven Yeun plays Ricky “Jupe” Park, a neighboring theme park owner who’s itching to buy up the ranch.

OJ and Em’s golden ticket just might be a UFO (yes, you read that right) that keeps zipping around in the sky over their land. If the siblings can capture a shot good enough to land them on TV, they figure they just might make it big enough to save the ranch.

None of this, however, explains why the film opens on a chimp sitting next to what appears to be a dead body—or why that chimp turns out to be the film’s most tragic figure.

From the roadkill deer at the start of Get Out to the army of bunnies living among the tethereds in Us—and now this chimp—animals are a recurring motif in Peele’s work. When asked about these touches in a recent interview with Washington, D.C.’s Fox 5, the director observed that animals can be “a reminder of how we treat anything that doesn’t qualify as human.”

“There’s a real-world horror that animals are trapped in,” Peele said. “In some ways, they symbolize something very bad about us. That’s what my movies are about. It’s about how bad we are.”

That thematic thread felt fairly subtle across Peele’s first two movies, but Nope makes it brutally stark.

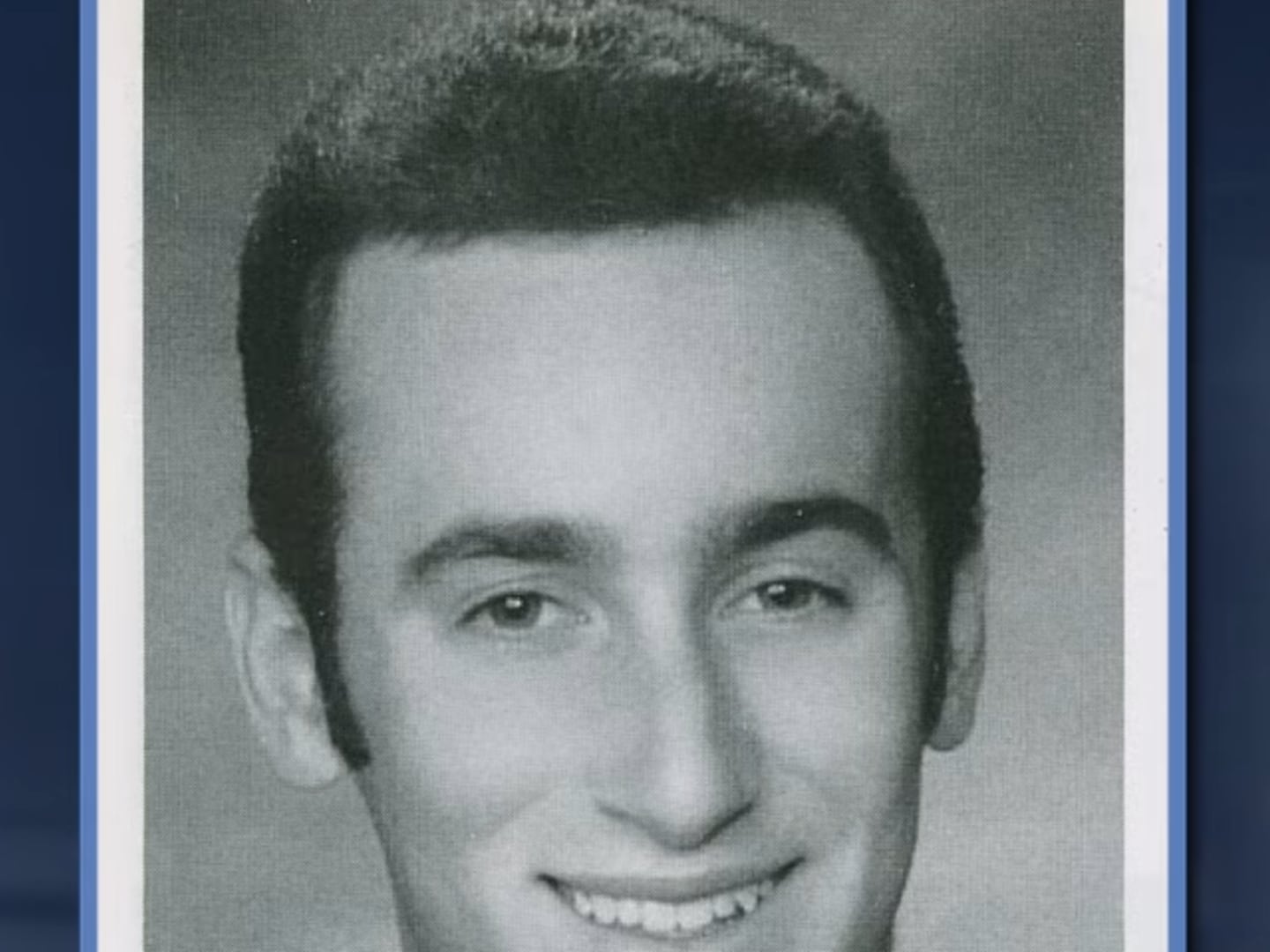

As a child actor, Ricky—also known as “Jupe”—appeared on a short-lived sitcom called Gordy’s Home. (Think: Full House vibes.) “Gordy” was not a human boy, however, but a live chimpanzee. During a birthday party scene, a popped balloon sends the hairy primate into a violent, murderous fit. In his darkened office, Ricky recounts a version of the story to OJ and Em—the one that aired on Saturday Night Live, starring an “undeniable” Chris Kattan—with unsettling glee.

But much like the sanitized vision of the wild, wild west Ricky’s selling outside, the SNL version of the Gordy’s Home massacre leaves out the real dark part of the story. We see it in wordless flashback: After bloodying two of 8-year-old Ricky’s cast mates in front of him, the chimpanzee wanders over to the child star. Instead of attacking, however, Gordy performs the human gesture of affection he’s been taught for a recurring bit for the show—an exploding first bump.

As a terrified Ricky raised his own fist to meet Gordy’s, someone shoots the ape, splattering his blood across the young boy’s face.

In spite of what our horror-movie monsters so often tell us, proximity between humans and animals is typically more perilous for the so-called “beasts.” Stories about dolphins and other sea creatures dying at the hands of selfie-hungry tourists who hoist them out of the water are all too common, and that excludes all the animals we hunt for sport. Even at our most well intentioned, humanity tends to anthropomorphize animals to their peril.

The chimpanzee—a creature that has enraptured scientists and the public alike with its capacity “human-like” behavior—is the perfect vehicle for that message.

When I watched Gordy reach for Ricky’s hand only to get shot, I found myself crying—a reaction I must admit I hadn’t quite expected from a film that, based on the trailers, looked like a lighter UFO adventure. But that scene is devastating: The chimpanzee—who has been held captive from his habitat, isolated from his species, and trained to behave like a human for entertainment throughout his life—is reaching out with one final gesture he’s been trained to think of as “friendly” but does not actually understand. Then they shot him.

What gave us the right to put him on that soundstage in the first place? The moment crams Nope’s full indictment of humanity into one tragic shot.

There’s some irony to the fact that Nope—a film that actively critiques humanity’s assumption that our interests are superior to animals’—has been compared to Jaws. Valerie Taylor, a diver who worked alongside her husband to film the shark scenes in that film, has since expressed regret for the panic the film stoked among beachgoers. (The reality, in fact, is that human-shark contact is, statistically, worse for the sharks than it is for us; they remain more imperiled than humans thanks to fishing activity.)

Beyond “Gordy” the chimp’s actual death, the true tragedy of his fate is Jupe’s complete inability to process it. As a theme park owner, the onetime child actor remains fully dependent on spectacle to make a buck. And evidently, surviving an on-set chimp attack has only convinced him he can similarly charm an alien species, bend it to his will, and milk the whole endeavor for a profit.

Even Jupe’s former cast mate, who wears a scarf over her face to hide her disfigurement from the chimpanzee attack, can’t help but turn up for the show. When the sheer fabric billows in the wind, revealing her scarred face and milky eyes as they stare up into the sky with a mixture of fear and wonder, viewers must sit face-to-face with one of the grimmest realities of humanity: We just never know when to say, “enough.”