A great believer in karma, and nearly as frank in his confessions as he was exuberant in his self-advertisements, Norman Mailer was surely convinced that he would get the biography he deserved. Well, there have been five so far, the first four published in the 1980s and 90s. The most recent, a great big, messy love letter, is about to land with a dull thud in your neighborhood bookstore. Maybe it’s quantity that counts in this particular karmic equation, and the proliferating accounts of Stormin’ Norman’s earthly transit are an indication of his great virtue as a writer. Or perhaps poetic justice demands that the life of an unstoppably prolix author be parceled out in multiple, overlapping volumes.

If you ever felt you needed more Mailer, J. Michael Lennon Norman Mailer: A Double Life is just the ticket. At 950 pages, it’s the longest of the five biographies and the most complete—if only because it’s the only one to report on his last decade and to portray the scene at his deathbed at the Mount Sinai hospital in Manhattan in November of 2007. It’s authorized, too: Mailer gave Lennon the green light, telling him to “put everything in.” But is it definitive? Nope. There’s plenty left out, including what Mailer made of the first four attempts to pin him to the page. Lennon’s biography is sloppy, unfocussed, and adoring—and likely, therefore, to spawn others, written in reaction. Brace yourselves.

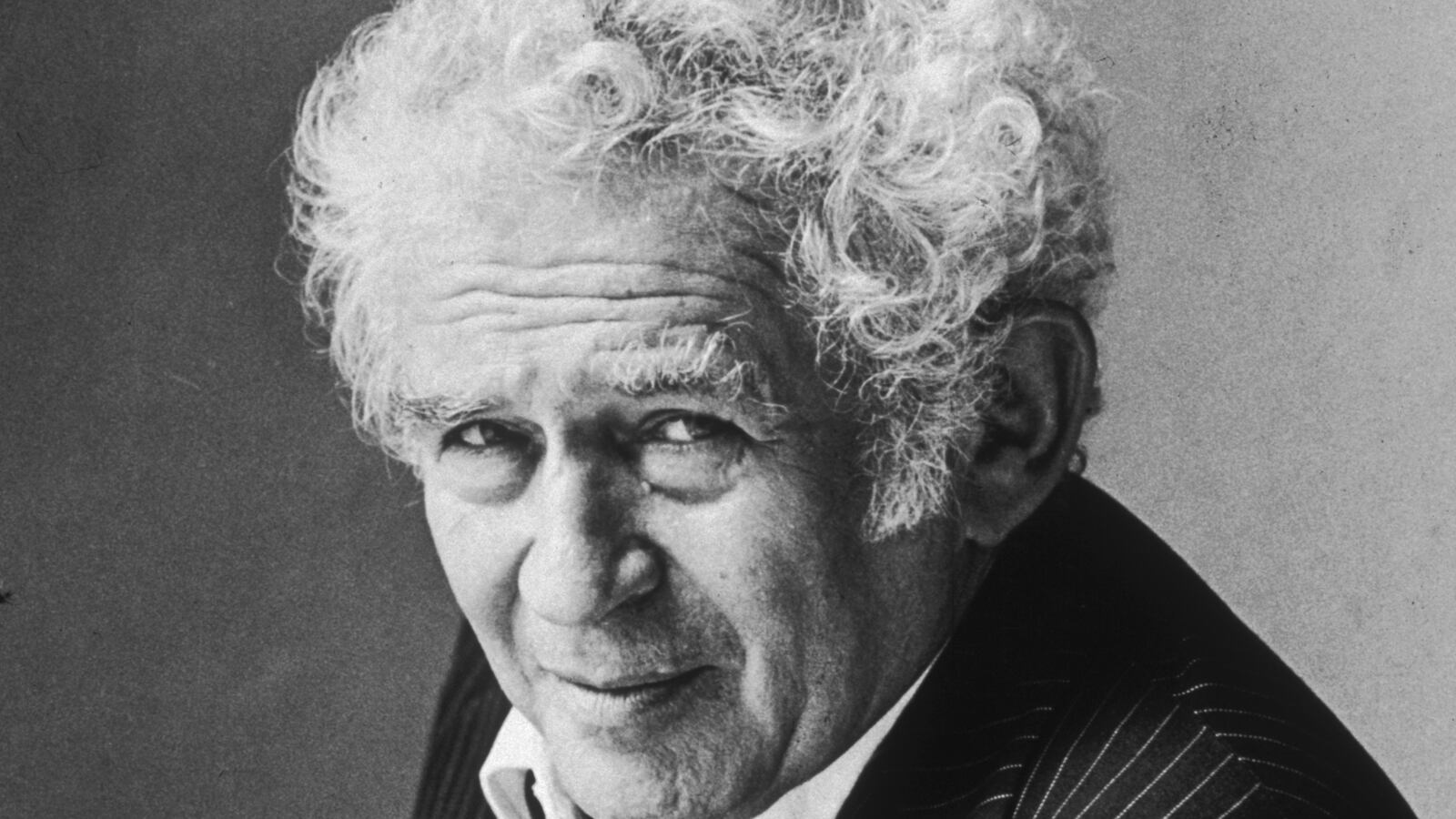

Who would not want to write the life of a character as compelling as Norman Kingsley Mailer? Born in Brooklyn in 1923, he attained celebrity status at age 25 with an explosive bestseller; kept himself in the public eye with every kind of bold and lurid gesture, from stabbing his wife to running for mayor of Gotham; wrote a handful of extraordinary books, many others of enduring interest, and at least a dozen stinkers; engaged mano a mano with just about every significant public issue of his time; head-butted a dazzling collection of fellow celebrities; and battled his way into his 85th year with his wit, his charm, and his appetites more or less intact. At age 83 he wrote in a letter, “I take pleasure in announcing to friends that I once could boast of a seven and a half inch column of silver dollars, but now I’m down to half a roll of dimes.” Had he given up the game? Fat chance. There was still time, in the 27th year of marriage to his sixth wife, to meet up with an old girlfriend or two.

Where did he get his unrelenting priapic urge? His bubbling brains? His rabid hunger for artistic success? His infinitely expandable ego? This is the sort of question we keep foolishly hoping a biography can answer. Lennon offers plausible clues: Norman’s father was a ladies’ man; Norman’s maternal grandfather (a rabbi in the old country, in New Jersey a peddler then a grocer then a hotelier) possessed an uncommonly keen intelligence; Norman’s mother adored him, treated him like a young prince, and prayed for him to be a great man. Plausible but hardly proof positive. Through no fault of Lennon’s, the mystery of outsized talent remains a mystery. There was no shortage of smart Jewish boys from Brooklyn, all of them adored by their mothers, but only one of them spent 50 years in serious contention for the heavyweight title in American letters.

World War II gave him his material, as he knew it would. Within 48 hours of the bombing of Pearl Harbor, he was “worrying darkly” about which theater of operations would be more likely to yield a great war novel: Europe or the Pacific? Drafted, he was shipped off to the jungles of the Philippines and spent over two years on active duty. He didn’t see much combat, but came away with enough experience to produce his bestselling debut, The Naked and the Dead. Brutal, bleak, and engrossing, it’s also grandiose and bloated. It revealed his vulnerability to ideas, ideology, and mystic hoo-ha. He was thinking big from the beginning, which is admirable but not always conducive to taut storylines.

In a letter to the novelist Vance Bourjaily he stressed the importance of experience and waved aside theme as “afterthought”—and then confessed, charmingly, that in The Naked and the Dead, “really what I wanted to say was ‘Look at me, Norman Mailer, I’m alive, I’m a genius, I want people to know that.”

Halfway through his army tour he wrote to wife No. 1, “You know really my only decent function as a man is to be a lover and/or an author.” Indefatigable in those two roles, he hankered after others, as well. Hollywood tempted him, as did politics. If he’d had sufficient talent to box professionally, nothing could have kept him out of the ring. And he also came close, in the late ’50s and early ’60s, to devoting himself to addiction: to cigarettes, to booze, to marijuana, which he liked to call “tea.” Many of the pieces stitched together to form the outrageous ego exploration and hipster effusion that is Advertisements for Myself were written under the influence.

We can assume he was well-lubricated at a Lillian Hellman dinner party in 1958 when he turned to Diana Trilling and said, “And how about you, smart cunt.” They became fast friends.

He was drunk and high when he stabbed wife No. 2 at the end of a long, raucous party two years later. He stabbed her twice with a penknife, and one of the wounds was potentially fatal. The wife survived, the husband was committed to the violent ward of Bellevue Hospital for three weeks, after which he was declared “not psychotic.” Three months later he met wife No. 3.

He had moved on to wife No. 6 by the time the next stabbing occurred. While working on Executioner’s Song, he began a correspondence with a convicted murderer named Jack Abbott. Thanks in part to the efforts of Mailer and several other New York literary types, Abbott was paroled in June of 1981. Less than six weeks later, Abbott plunged a knife into the chest of a 22-year-old waiter, killing him almost instantly—an apparently motiveless act of violence. To his credit, Mailer accepted blame, perhaps more blame than he deserved. But then he always craved more than his fair share.

Six wives, nine children. The money flowed out in alimony and child-support payments, and flowed in as advances for books that were always late and sometimes non-existent. The last words of Harlot’s Ghost were “TO BE CONTINUED.” The sequel, Harlot’s Grave, never materialized.

There is no trajectory to Mailer’s career (or if there is, his latest biographer failed to discover it). He was a serial self-inventor, careening from triumph to disaster and back again. From this distance, it seems his best writing was done on the cusp between fiction and nonfiction, the indeterminate zone where Advertisements for Myself, The Armies of the Night, and The Executioner’s Song work their powerful magic.

Because Norman Mailer: A Double Life is an authorized biography and Lennon can quote freely from both published and unpublished writings, Mailer’s voice comes through loud and clear. So do the voices of his critics: Lennon is constantly reporting on the good, bad, and ugly reviews that attended each new publication. But a running tally is no substitute for a comprehensive critical view. I’m not asking for a definitive judgment, just for some gentle authorial guidance.

Back in the late ’60s, something extraordinary emerged from all the bad behavior of our self-styled “psychic outlaw”: He created a persona that carried his writing and bound it together. The prime example is The Armies of the Night, the first stirrings of New Journalism, in which the author records the rollicking adventures of a “semi-distinguished and semi-notorious author” called Norman Mailer; this character is our guide and companion as we march on the Pentagon to protest the Vietnam War in October of 1967.

Unfortunately, J. Michael Lennon tries something in the same vein in the last quarter of his sprawling biography. He turns himself into a character called “Lennon.” At first he’s “a young professor at the University of Illinois-Springfield.” Later we learn that “Lennon and his wife had purchased a condo about a mile and a half from the Mailer home” in Provincetown, RI. We’re treated to excerpts from “Lennon’s ‘Mailer Log’”—notes on his interaction with the aging author. There’s no need for this coy maneuver. The biographer’s job is to digest and transform raw data. Here he’s just blurting it out.

Which brings me back to poor Norman’s bad luck with biography. Of the major American authors of the 20th century, only his beloved Hemingway had a more action-packed life and a more formidable personality. It took time, but Hemingway eventually met his match in the incisive Kenneth Lynn. When will it be Mailer’s turn to be written about with the verve and brilliance that are the hallmarks of his own best work?