When Norman Manea was five years old, he was shipped to a concentration camp in Transnistria, Ukraine. In 1941 Jews from Northern Romania were deported there, via freight trains, on the order of Marshal Ion Antonescu, the country’s far-right dictator and an ally of Hitler. Technically, in the camp you were not killed, you were left to die slowly. Chronic starvation, overwork, disease, and freezing temperatures were as effective as the bullet, only slower and crueler. Compared to Hitler’s factories of death in Poland, Antonescu’s Transnistria “did not live up to expectations and could only show a balance sheet of 50 percent dead. It that respect, it could not compete with Auschwitz,” says Manea in his volume of memoirs, The Hooligan’s Return.

Although he was meant to die, Manea survived. Indeed, this was only the opening episode of what was to be a biography informed by an extraordinary “art of survival,” as the book documents in detail. In 1945, along with whoever survived from his family, he returned to Romania. They thought they were going back to their old country, but that country was not anymore; what they found instead was an alien land. Romania’s participation in World War II had changed dramatically its social, political, and cultural landscape. Moreover, the hectic Stalinization that was then taking place didn’t exactly facilitate readjustment. This is the place where Manea came of age, and where he was to put his survival skills to new use.

For a while it looked as though the newly installed political regime could fix the evils of the previous one. As we go deeper into The Hooligan’s Return, we see an adolescent Manea getting drunk on high hopes of universal happiness and Messianic renewal. The promising high school student allowed himself to play a role in the masquerade of political meetings and excommunication campaigns, but he got out in time. The hangover was as painful to endure as it is embarrassing to recount. Meanwhile, things in Romania were not getting any better. When Nicolae Ceauseşcu added a strong nationalist ingredient to the totalitarian concoction, it became obvious that, on closer inspection, the two oppressive regimes, the fascist and the communist, were hardly distinguishable: “The new horror had not only replaced the old one but had co-opted it: they now worked together, in tandem.” In Romania of the ’70s and ’80s, Manea had to sharpen his survival skills and bring them to perfection.

As we’ve learned from Orwell, totalitarianism is in an important sense a linguistic project; the most efficient means to control people’s lives is to occupy the language they speak. Behind the Iron Curtain, Manea had the opportunity to observe this colonization of sorts at close quarters. To understand what is going on, you always have to practice suspicion, never take the official language at its face value, always look for some hidden meaning. “Reading between the lines became the normal practice. The weight of adjectives, the violence of verbs, the length of the argument gave the measure of how serious the situation really was and how stringent the remedy was going to be.” The Party’s language, notices Manea in his memoir, was “a language of encoded terminology, charades, a restricted, monotonous language that only served to undermine people’s confidence in words,” which often made existence under totalitarianism a lifetime adventure in language and interpretation. That’s why, in the end, the regime’s main exports, apart from cheap wine and textiles, were writers and experts in hermeneutics.

For someone as fascinated with the multiple uses of language, with codes and charades, as Manea was, it is no wonder that he ended up doing literature. As luck would have it, he became a writer in a world where good literature was almost always subversive literature; those who ruled that world were afraid of the writers’ craft because they saw it as clashing with their own linguistic project. (One can hardly pay literature a greater compliment than to deem it dangerous, be it said even in passing.) Having had to perform on such a competitive stage, Manea became quite a sophisticated writer in Romanian: as though in response to the totalitarian regime’s linguistic aggression, he sought to gain access to deeper and deeper layers of language, to regions where power could not possibly penetrate.

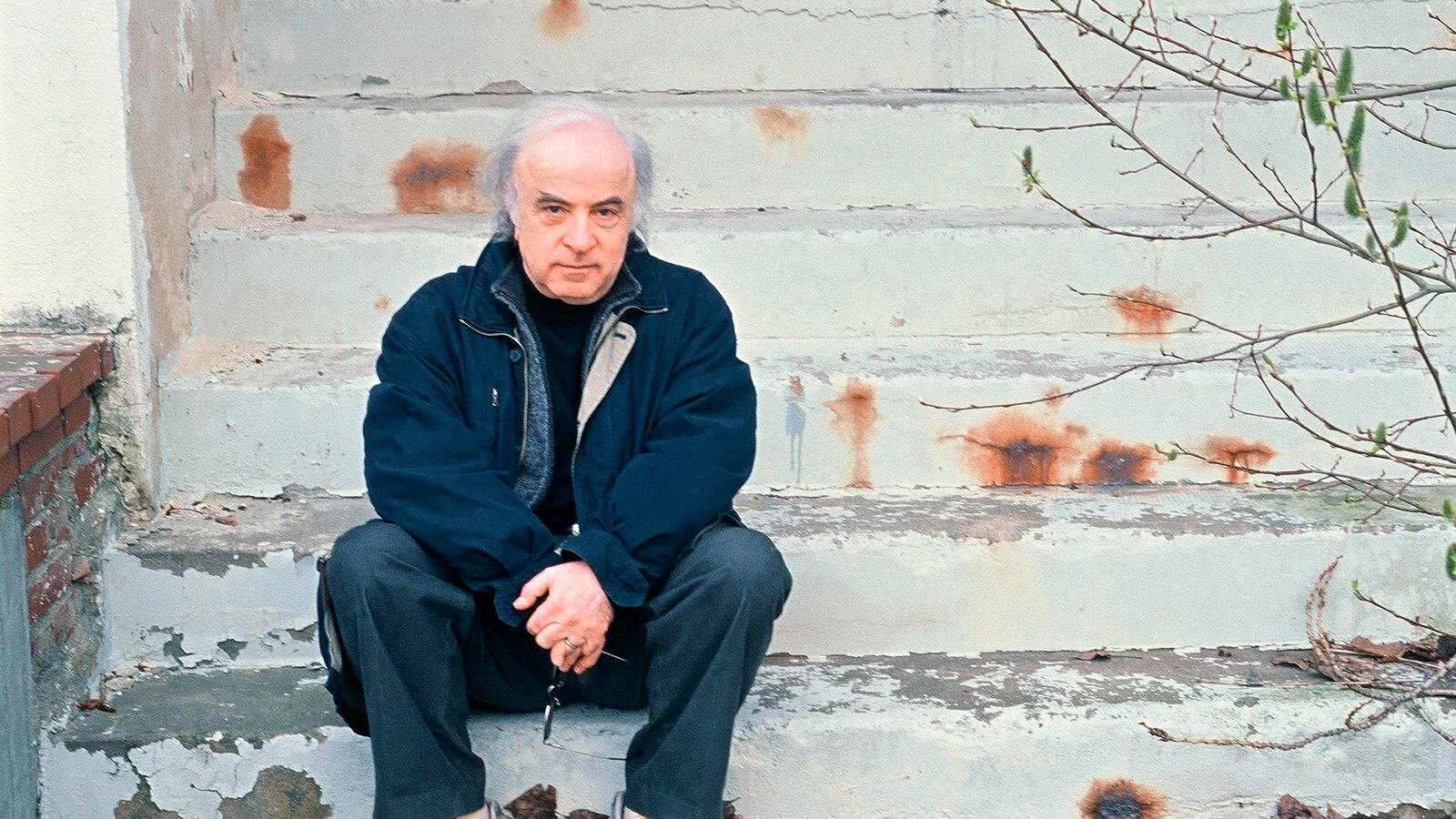

As Ceauseşcu’s regime grew more demented, Manea grew more impatient. He recounts, for example, how in the spring of 1986 Bucharest “had reached levels of degradation for which even sarcasm was no longer sufficient. Not even the chimeras could survive in the underground labyrinths of Byzantine socialism.” For a long time, Manea had thought that, as a writer, he could only live in the Romanian language—as he saw it, he could not leave the country and stay alive. And yet leave he did; he chose to exile himself—that is, to die and live posthumously elsewhere. In 1987 he moved to Germany, and one year later to the U.S. Since 1989 he has been teaching literature at Bard College. A professional survivor of sorts, Manea seems to feed on challenges, danger and adversity; indeed he has flourished in exile, turning it into one of the major inspirations of his recent work.

A 1997 trip to Romania allows Manea to recount this unique biography. A journey to a distant place occasions a greater, more consequential journey in time—“a voyage to my own posterity,” he calls it. There are initially two Maneas in The Hooligan’s Return; one is Manea the memoirist who remembers and recounts his past; the other is Manea the chronicler who passively records the present. There is also something of a self-therapy in this journey, which he makes and writes about at the same time. As we get increasingly engrossed in the reading, we notice how the two authors gradually become one and a healing process takes place—right there, on page, before our eyes, as it were.

The country to which Manea returns in 1997 is a country that, once again, has become alien to him. This time, however, Manea discovers that he, too, has become a stranger to his countrymen. He is in fact worse than that. While abroad Manea has written extensively on Romania, looking mercilessly into its totalitarian past and calling into question some of its “greats” (Mircea Eliade, for example). As someone who has shaken the country’s idols, Manea is worse than an alien—he is a myth-breaker, a trouble-maker, a hooligan. Hence the title of these haunting memoirs, which covers almost 80 years of surviving.