Norris Church Mailer died Sunday and her friend Lawrence Schiller offers his memories of their first meeting, how she tamed her legendary husband, Norman Mailer, and her great wit. Plus, rare photos of the famous couple.

It was 8 a.m. in California when John Buffalo Mailer called me to say that his mother, Norris, had died a few minutes earlier in the Brooklyn Heights home she’d shared for more than 30 years with my longtime friend Norman Mailer. Norris had been ill with cancer for 11 years. John and his brother Matthew were at her side when she died. Now, three hours later, after The Daily Beast asked me to compose some thoughts, as I fly back toward New York, memories flood my mind and the words to describe them do not come easily. Norris was Norman’s sixth wife and the one who came to care for him and love him the most, and in that love she found the way to make Norman a better person. He owed so much to her and she asked so little in return—that’s my opinion on the subject. She made her own feelings known in her recent memoir A Ticket to the Circus.

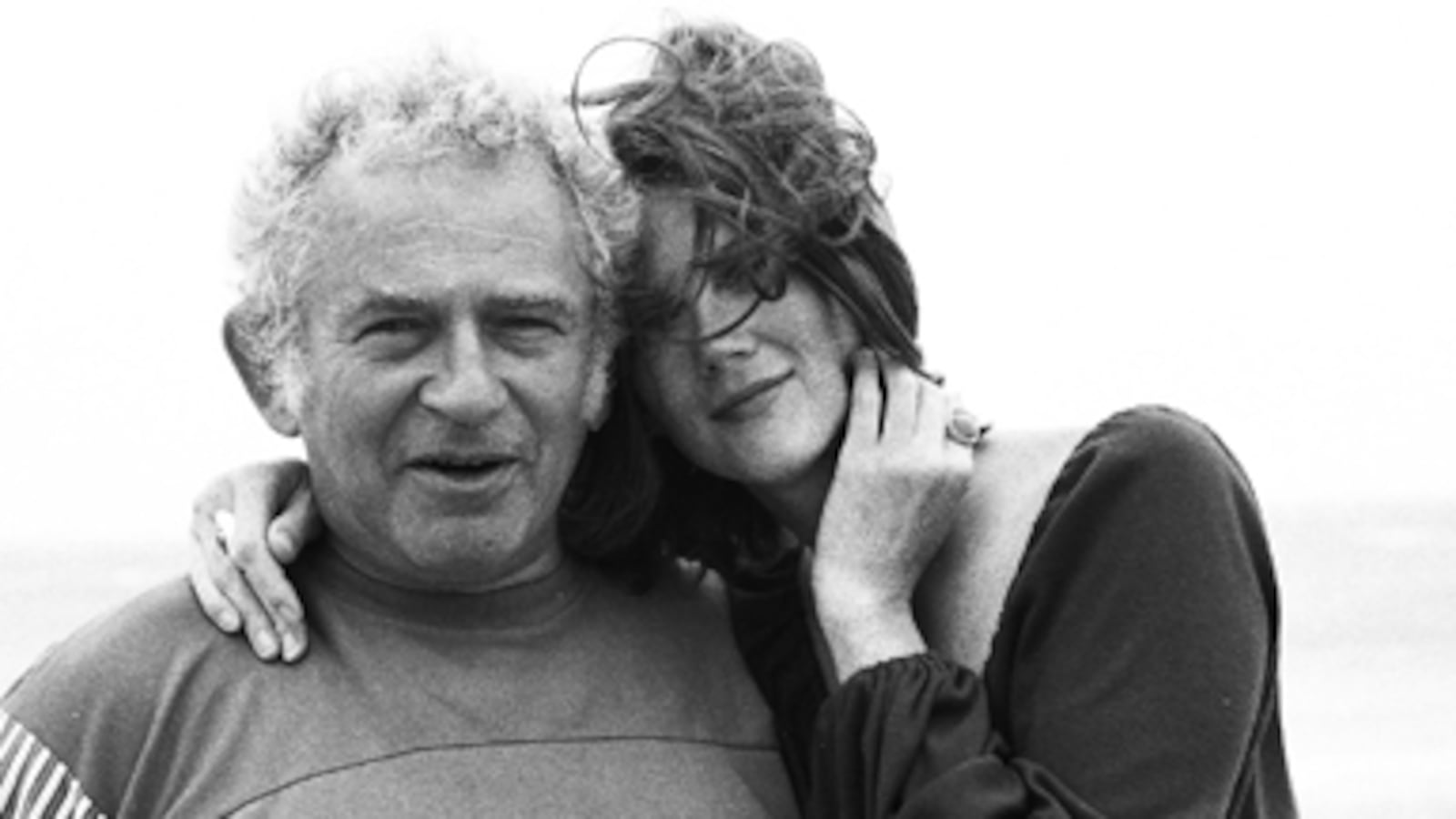

I met Norris for the first time in 1975, at the Manila airport. Norman was due to arrive to cover the Ali-Frazier fight in the Philippines and I was there to photograph it for Time. Both Norman and I were between marriages. When he showed up in the arrival hall of the airport, a tall, beautiful young woman accompanied him, her arm wrapped tightly around him. She glided over the tile floor like a gazelle and had a face that Amedeo Modigliani would have died for. No, she was not Eileen Ford’s latest discovery; she was an art teacher from Arkansas whom Norman had just met. I took Norman aside and said, "You’d better hurry up and marry her, otherwise I will."

Norman’s reputation with women was always controversial. His views on feminism, his outlandish statements, his drinking in public, his constant challenging of authority, his public debates with Gore Vidal, and all those battles with all his ex-wives. How long would this woman—she was just 26—last with a man twice her age? I wondered.

Yes, she loved the parties they were invited to night after night, and, yes, she loved becoming a model and being photographed by the best. Soon they were the subject of dinner chatter in New York City. She might even have enjoyed that, too. But all the time she was also a woman about to come into her own. As their son John Buffalo was born in 1978 and Norman married her in 1980 and adopted Norris’ first child, Matthew, she slowly emerged as a force of her own.

Norman didn’t stop being Norman, but Norris started to manage his life in a manner that he would slowly accommodate. They had long, drawn out fights over his drinking, his language, his late nights out. Still, she knew how to handle him—"Jewish boys need to be taught what it’s all about," she once said to me, a twinkle in her eye just like the twinkle in Norman’s. She left him alone when he needed to write. And write he did.

I loved them both. They were perfect together.

Under her influence, a new voice also emerged in his work. I started to see it when Norman and I began work on The Executioner’s Song, which would go on to win him his second Pulitzer Prize.

• Norris Church Mailer Reviews Antonia Fraser’s MemoirStill, he and Norris fought. She would let him have it, in her Southern drawl, again and again. She let him know that she would not put up with his womanizing. And when it got too much, she would just move out with John Buffalo. I could never figure out if Norman went running after her or whether she came back to show him just how much she loved him. It was clear, though, that she had her conditions and that Norman met them. He could no longer live without her. And her love for him was plain for all to see.

Norman had seven children by five wives by the time he met Norris. And she took it upon herself to bring his family together each summer in Provincetown, where she and Norman retreated when they got tired of New York society and he needed to write. In the early years, the kids slept in sleeping bags all over the house, sometimes two or three to a room. As the Mailer children grew and married and had children of their own, they came back each summer for weeks at a time, and the family grew closer under the guidance of the shepherdess Norris. During my visits to Provincetown, I marveled as I watched the family cook, sing together, and play on the beach together. Little by little, the children grew to love Norris as much as—and maybe, in some cases, even more than—they loved their father. She cared for them as she cared for their father. She spoke her mind to them as she did to their father, and they respected her for that.

They were proud to witness Norris come into her own, as Norman was. She began to paint again, she wrote books on her own without any interference from the other writer in the house, and she enjoyed sitting at the bar with Norman at the end of each day, looking out at the bay and going over the events of the day and planning those on the horizon. Norman cut down on his drinking as his heart condition worsened and when Norris came down with cancer. When she first got sick, she told me she was sure she would die before Norman. But she outlasted him.

I last saw Norris a month ago at the second annual gala for the Norman Mailer Center and Writers Colony, which she and I co-founded in 2008 after Norman’s death. When I spoke to her on the phone 10 days ago, her final words to me were, “Larry, I will not last this year.” She was right.

I loved them both. They were perfect together. Thank God they found each other.

Plus: Check out Book Beast for more news on hot titles and authors and excerpts from the latest books.

Lawrence Schiller began his career as a photojournalist for Life magazine and the Saturday Evening Post. He has published numerous books, including W. Eugene Smith's Minamata and Norman Mailer's Marilyn . He collaborated with Albert Goldman on Ladies and Gentleman, Lenny Bruce, and with Norman Mailer on The Executioner's Song and Oswald's Tale . He has also directed seven motion pictures and miniseries for television; The Executioner's Song and Peter the Great won five Emmys.