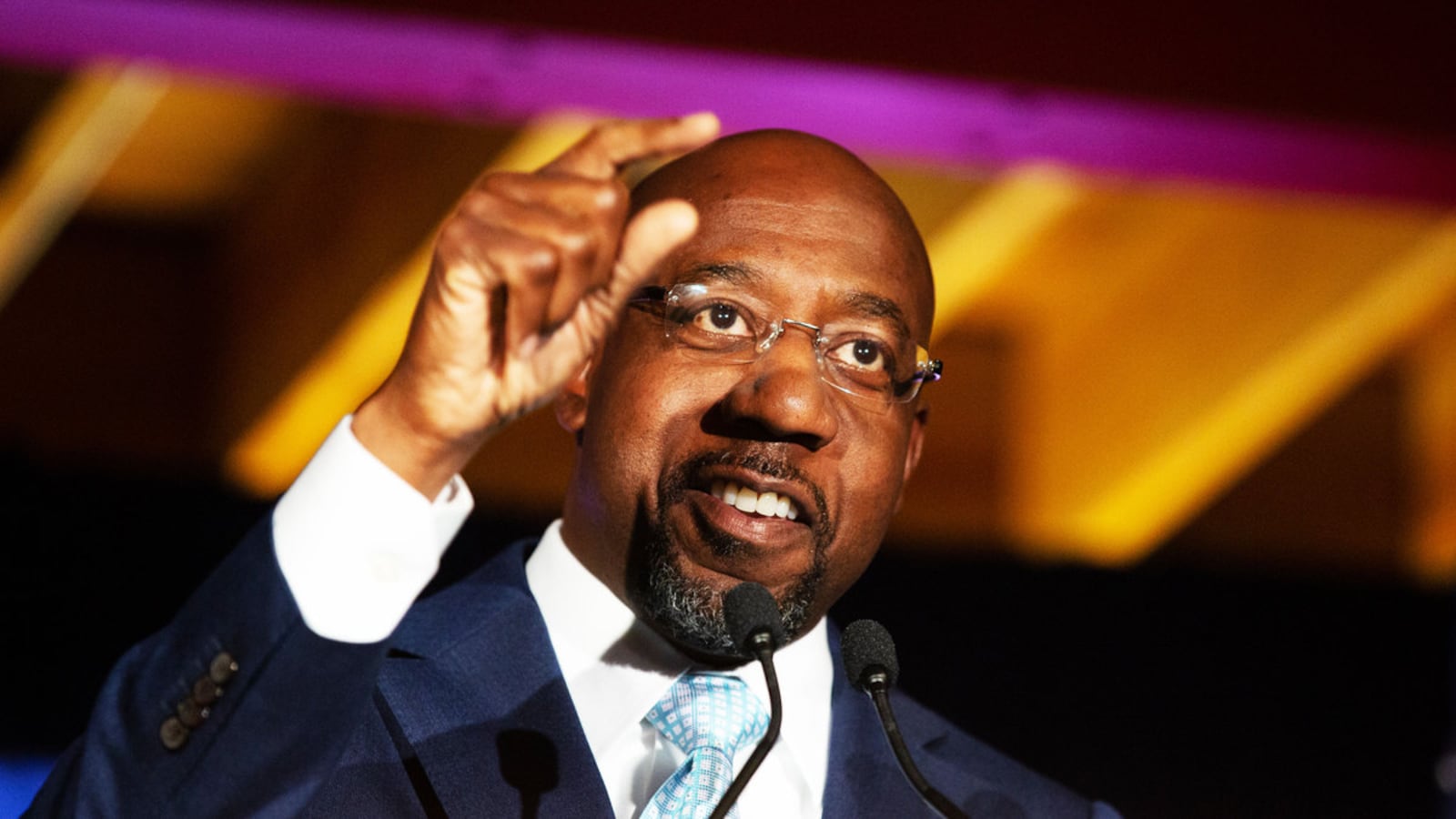

“We don’t like to talk about these things in church,” the Rev. Raphael Warnock cautioned the congregation at Atlanta’s storied Ebenezer Baptist Church in March 2010, but “I’m very convinced that if Martin Luther King, Jr. were alive today, he would be focused on the issue of HIV/AIDS.”

He then stepped back from the pulpit, sat down at a nearby table, and in front of the church’s 1,700 congregants, swabbed his gums to take a rapid OraQuick HIV test.

As Warnock campaigned in a historic U.S. Senate runoff amid the dark winter of the coronavirus pandemic, he has made addressing the virus—and its disproportionate effect on Georgia’s Black communities—a centerpiece of his run. But the 43-year-old Democrat has dedicated much of his life as a pastor and social justice activist to combatting another epidemic that has uniquely harmed Black Americans: HIV/AIDS.

“Not all pastors do that,” said James Curran, a professor of epidemiology and an HIV/AIDS expert at Emory University in Atlanta. “Early on, it was a very controversial topic in churches—that’s true in Black churches, white churches, evangelical churches, Catholic churches.”

Many churches didn’t want to touch the topic, Curran told The Daily Beast—or if they did, “they wanted to accept the sinner but not forgive the sin.”

As the respected pastor of one of the nation’s most revered Black churches—whose pulpit King preached from—Warnock has been in a unique position to fight what he frequently calls “the unholy trinity” of silence, shame, and stigma surrounding the virus. And he has taken on that project in a city where HIV/AIDS infection remains dangerously higher than elsewhere in the U.S.

Warnock’s campaign did not make him available to The Daily Beast for an interview in time for this article’s publication. But half a dozen HIV/AIDS experts and advocates in Georgia said that the reverend-turned-candidate has indeed walked the walk on preventing the disease, from dramatic gestures aimed squarely at stigma, to behind the scenes work on the finer points of policy—work that informs Warnock’s thinking on broader health inequities and the COVID-19 pandemic unfolding now.

In many respects, there are clear connections between HIV/AIDS and COVID-19. Like HIV, it has devastated Black communities in the state Warnock hopes to represent in the Senate—Black Georgians accounted for 80 percent of hospitalizations due to the virus when it first hit in March, researchers from Atlanta’s Morehouse College later found.

“We see in COVID the same sort of health inequities that we have seen for decades with HIV,” said Melanie Thompson, an Atlanta doctor who has worked on AIDS advocacy, research, and public policy for several decades. “If anything, COVID has magnified the existing disparities.”

But the pandemic has also cut across communities of every demographic in rural Georgia, where eight hospitals have been closed down due to lack of funding over the past 10 years, something Warnock has emphasized on the campaign trail.

“The virus has devastated the Black community in ways that are disproportionate,” Warnock told The American Prospect last month. “But as I move across disaffected, rural communities across Georgia, white sisters and brothers are suffering and wondering why the conversation in Washington is so disconnected from their actual lives.”

Warnock may soon get a chance to be one of 100 U.S. senators shaping policy on the COVID pandemic. But when it comes to the epidemic he’s already spent much of his life working on, few people in Georgia have had the unique kind of impact Warnock has, say those familiar with his work.

“My argument is that the symbolic precedes the structural,” said Charles Stephens, an HIV/AIDS activist in Atlanta and the founder of the Counter Narrative Project, an advocacy group for Black gay men. “I wouldn’t be quick to dismiss the value of symbolism… because of the number of people he can reach, because of what he represents.”

“That being said, that shouldn’t be the endpoint,” Stephens told The Daily Beast. “My hope for Rev. Warnock is that… he continues to use his platform to not only bring attention to HIV, and to inspire people to respond, but also to connect to HIV/AIDS as a racial justice issue, to look at institutional failures.”

Activists say that if Warnock is elected come Jan. 5, it may be the first time ever that a freshman senator arrives in Washington already steeped in the work of HIV/AIDS advocacy. And there are signs that Warnock, if elected, would make combating HIV/AIDS a key part of his portfolio as a lawmaker: his Senate campaign website, for instance, devotes a page to LGBTQ issues and touches on funding for PrEP, an HIV prevention drug.

Local HIV/AIDS advocates, like Jeff Graham, can’t remember the last time, if ever, that a U.S. Senate candidate in Georgia devoted prominent space on their platform to this issue in such a way. Graham, the director of the LGBTQ advocacy group Equality Georgia, said he’d bring a unique perspective to the issue on Capitol Hill.

“Frankly, even though there’s been support from U.S. senators of both parties in the past, we haven't had that sort of strong personal connection and experience of what day to day life is for people with AIDS,” he said.

That connection began in Baltimore, two decades ago, when Warnock took the first head pastor job of his career, at Douglas Memorial Community Church. In the early 2000s, HIV/AIDS cases were on the rise, rising past the 10,000 mark in the city. Of all cases, nearly 90 percent were among Black men and women.

“Everything I do is theologically and biblically informed,” Warnock told the Baltimore Sun in 2001, weeks before he took the reins of one of the city’s largest and most influential churches. Quoting the Old Testament prophet Hosea—”My people are destroyed for lack of knowledge”—Warnock warned that willful ignorance about HIV was hollowing out the communities that he was seeking to serve.

“That is literally the case with regard to HIV/AIDS,” Warnock said at the time. “People do not know what they need to know about the virus itself, and they do not know their HIV status. If the clergy went to get tested en masse, we could create a climate where you remove the stigma.”

Warnock’s passion for fighting the epidemic followed him to Atlanta, which has become a national hotspot for new infections, particularly among Black communities. Georgia ranks among the top five states for new HIV infections nationwide—it had the highest rate per capita of any state in 2018—and AIDS is the leading cause of death for Black men between the ages of 35 and 44 in the state. In 2018, Atlanta’s case rate reached such heights that the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, based in Atlanta, likened the city’s rate of infection to those in sub-Saharan Africa.

Graham said that he served with Warnock on an HIV/AIDS advisory board in Atlanta, shortly after the young preacher first arrived there from Baltimore in 2005, at a time when focus centered on getting federal and state dollars toward prevention measures.

In sermons, public remarks and newspaper editorials, Warnock has frequently invoked the words of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. to push for greater national focus on the epidemic—particularly in light of the fact that, as he noted during a special interest session on the HIV/AIDS epidemic in 2008, “as the epidemic has swung to people of color, the money has not followed.”

“One can almost hear Dr. King’s voice thundering from the crypt,” Warnock wrote in a 2003 opinion piece in the Baltimore Sun in the leadup to the Iraq War. “‘A nation that continues year after year to spend more money on military defense than on programs of social uplift is approaching spiritual death.’”

Following in King’s example, Warnock would later take his work on combating the epidemic to those in power. In 2014, he was arrested outside the state capitol while protesting Republicans’ refusal to expand Medicaid. Three years later, he was again arrested in Washington, D.C. during a protest in the rotunda of the Russell Senate Office Building against President Donald Trump’s proposed budget cuts.

The budget would have slashed funding for PEPFAR—the federal program aimed at combating HIV/AIDS in the world's poorest countries—by 17 percent, and totally eliminated federal funding for AIDS education and training centers.

After his arrest, he told reporters that “the national budget is not just a fiscal document, but a moral document,” and that in light of those who would suffer from the cuts to social and health services, “my getting arrested is a small price to pay.”

Allies of Warnock’s also say that his focus on HIV/AIDS is inextricably linked with the issue he’s putting at the forefront of his campaign, health care. Nan Orrock, a Democratic state senator who is a friend and neighbor of Warnock’s, talked about his involvement in the years-long push to expand Medicaid in Georgia, something that he has pledged to do on the federal level if elected.

A string of GOP governors in Georgia have successfully blocked the option to expand Medicaid, which would be backed by federal dollars under the Affordable Care Act, while deep-red states like Idaho and Nebraska have chosen to do so.

Advocates view that as a serious obstacle to HIV/AIDS treatment in Georgia. Expanding Medicaid, said Orrock, would be “critically important in the battle to protect people from HIV infection, and to provide life-saving health services when you’re battling HIV.” Warnock’s commitment on the issue—evinced by his arrests, said Orrock—“speaks for itself.”

But Warnock has also sought to work within government to address the HIV/AIDS crisis within Black communities, putting his considerable influence behind the National Black Clergy for the Elimination of AIDS Act, landmark legislation that would create targeted grants for faith-based organizations to provide HIV testing, prevention services, and community outreach.

If elected, HIV/AIDS advocates hope that Warnock would become one of the Senate’s most forceful advocates for increasing funding for the disease’s prevention and treatment—particularly for the Ryan White program, a federal initiative that provides treatment for roughly half a million people with HIV, usually from the neediest populations. The program has in recent years been funded at somewhat stagnant levels, experts say, though those in Georgia note that the previous occupant of the seat Warnock is running for, former Sen. Johnny Isakson (R-GA), was considered a reliable ally in increasing funding.

In response to an inquiry from The Daily Beast, Warnock’s campaign said that working to lower the cost of HIV/AIDS treatment and prescriptions will be among his priorities in expanding health care access more generally.

If he defeats Sen. Kelly Loeffler (R-GA) in the runoff, Warnock will be thrust into office as Congress and President-elect Joe Biden, in all likelihood, strive to put together a sweeping COVID-19 relief package after months of fruitless negotiations and gridlock.

Observers can’t help but note how Warnock’s work on HIV/AIDS positions him as an uncommon voice on COVID-19. While the coronavirus carries with it hardly any of the social stigma of HIV, there remains distrust within the broader public, and within the Black community in particular, about treatment measures, such as a forthcoming vaccine. A Gallup poll released on Oct. 17 found that six in ten Americans would agree to take an FDA-approved COVID-19 vaccine. But less than half of nonwhite Americans said they would agree.

The legacy of the Tuskegee experiment, in which U.S. government public health officials studied Black men with syphilis while denying them treatment in the mid-20th century, is alive and well, said Thompson, and several Atlanta public health experts concurred that the lingering deficit of trust is very real.

“I think building back that trust is not a matter of words and platitudes, it’s a matter of action,” said Thompson. “Warnock is the kind of guy who will walk the walk, put actions there that will help to rebuild trust.”

Harry Heiman, a doctor and professor of public health at Georgia State University in Atlanta, agreed, saying, “if there aren't targeted strategies specific to those communities being disproportionately impacted, we’re going to fail, in the same way we're trying to overcome historical failures in HIV/AIDS.”

Asked if Warnock might reprise his famous HIV test from the pulpit by taking a COVID test in front of congregants, or constituents if elected, his campaign said he will take a COVID-19 vaccine when available and recommended by medical professionals, and “in following science and trusted scientists, he will encourage others to do the same.”

Still, many experts couldn’t help but imagine the visual of Warnock reprising the display that turned his HIV advocacy into headlines, and spoke to his skill as a communicator. “Think about the politics of a Senator Warnock getting a COVID vaccination on television,” said Heiman. “He understands, literally, the power of the pulpit.”