You might say that the best fiction exists to disassemble expectations. Nature can be the same way, which is why, even when we understand the realities of fire, we’re still taken aback—in the modern, technologically-ramped-up age—when something like Notre Dame Cathedral becomes a sky-tethered conflagration.

You want to say, “Wait, shouldn’t we be able to stop this?” and “Surely it is possible with all of our advances to keep such a blaze from beginning?”

But that is not how nature works, nor how great fiction works; they’re both going to do what they’re going to do, and then we must adjust.

We have expectations when we come to a story in literature. For instance, there will be a protagonist, and normally that person will be a human, unless we’re in the sci-fi ambit or Franz Kafka’s brain. But here on earth, you expect to see a human at the center of a story. Victor Hugo did not quite see things this way when he published The Hunchback of Notre-Dame in 1831.

He was in his mid-fifties, and this was a man with a cause. You might even call it an extra-curricular cause, so far as the literary arts went. For Victor Hugo was in thrall to Gothic architecture, the way a self-described geek might be headlong into anime now.

Gothic architecture rose—and that is a key verb in this style—to prominence in the late Middle Ages. It was mankind’s upwards march upon the heavens, drama writ in spires, turrets, rib vaults, and flying buttresses. The structures looked to be frozen in acts of great bounding movement, like someone had hit the pause button as these limestone titans leaped in battle or journey, with great stakes at play.

Stone angels stood guard in suspended flight at strategic vantage points, lest some minion of Satan come flying around a corner gaining access to human vulnerability down on the ground below. This was architecture to inspire awe, and it reminded you, too, of your mortality, like the home offices of heaven just happened to be hanging over your head, so wise up. There was a darker element in the resolute grays, but at the same time, Gothic structures exuded warmth, perhaps because they could look like expansive candle sticks in mid-melt blown up to the size of towering buildings.

Victor Hugo, who beheld Notre Dame Cathedral often, had his ‘aha’ moment: This church, this piercer-of-the-skies, would be the central character of his next novel, an opus even by the standards of opuses, its Byzantine chambers mirroring the architectonic passions, and structural designs, of Notre Dame, the ne plus ultra in the Gothic style.

So: We have Mr. Gothic Architecture Buff, and he wasn’t against some fear-mongering, believing that it was the duty of the people of his age to preserve structures like Notre Dame Cathedral. If you haven’t read the nearly 1000 pages of The Hunchback of Notre-Dame, and someone mentions it to you, you’re going to think about the titular creature, who, thanks to various cinematic adaptations, became a horror bogey up there with Dracula, Frankenstein’s monster, the mummy, the Wolf Man, and the Phantom of the Opera. Despite him not being a horror bogey at all. It was the hauntingly dramatic intensity of the cathedral’s design that served as horror film substrate. It just looked of the stuff of our imaginations at Halloween, as much a part of that eldritch ecosystem as haunted castles, creaky old mansions on low-lying hills, and graveyards where it might as well perpetually be midnight.

But while this is a terror novel, in a way, it’s a terror novel about mankind’s devolution. A key theme of the book is that the arrival of the printing press is going to mean the death of Gothic architecture. It took a huge outlay of effort and genius to make art like Notre Dame Cathedral. The printing press, meanwhile, would mean that any fool could slap whatever on paper, and out it would go into the world. You might say Hugo envisioned it as akin to Twitter or Facebook, with the concomitant weakening of the written word, and, in following, the weakening of how capable we were as thinkers. A fear evinced in the book is that we are all going to go to mental flab, and when that happens, we’re going to start to screw up the good things we’ve managed to make to date.

Hugo was certain to have recognized, as he wrote The Hunchback of Notre-Dame, that Gothic architecture was falling out of favor. Paris was not quite in the Victorian age, but there was a sense of “Hmmm, that’s a bit much, isn’t it?” Life was hard enough; Gothic architecture was fatiguing in that it asked a lot even of your eyeballs. You couldn’t just set your gaze on a Gothic structure and know what it was all about. Your eyes had to travel, they had to work; you might say that your eyes had to think.

But so it goes with any great work of art, and any great prose work of art. There is topography in language, and a work of prose art has architectural qualities, from its multi-chambered plot-structure-voices-tone design, and how that will be engineered and executed, to what is happening, even, in each sentence. Letters in tandem with each other possess group shapes. There are rises, valleys, lower levels. These variations, subtle as they may be, impact us psychologically. We think architectonically, and Hugo’s fear was that we were losing this, as so-called progress marched on.

Hugo sets the novel, in a sense, in 1482, but that’s the external setting. The internal setting is the mind, where these preconceptions we’ve been discussing are not indebted to any time period. They’re belonging to a problem—the slackening of imagination. The trend towards the safe rather than the daring.

You get a beautiful story of friendship, between Quasimodo—try to knock that Disney-fied version of him out of your head—and Esmeralda, an ostensible odd couple who wasn’t that odd of a couple in the end. I think our very best relationships can follow that design model. Why? Because we were open to how they disassembled our expectations in the first place. Hell, a “meet cute” story is often predicated upon that disordering of expectations and building up the blocks in a way different than we normally do at other, more prosaic points in our lives.

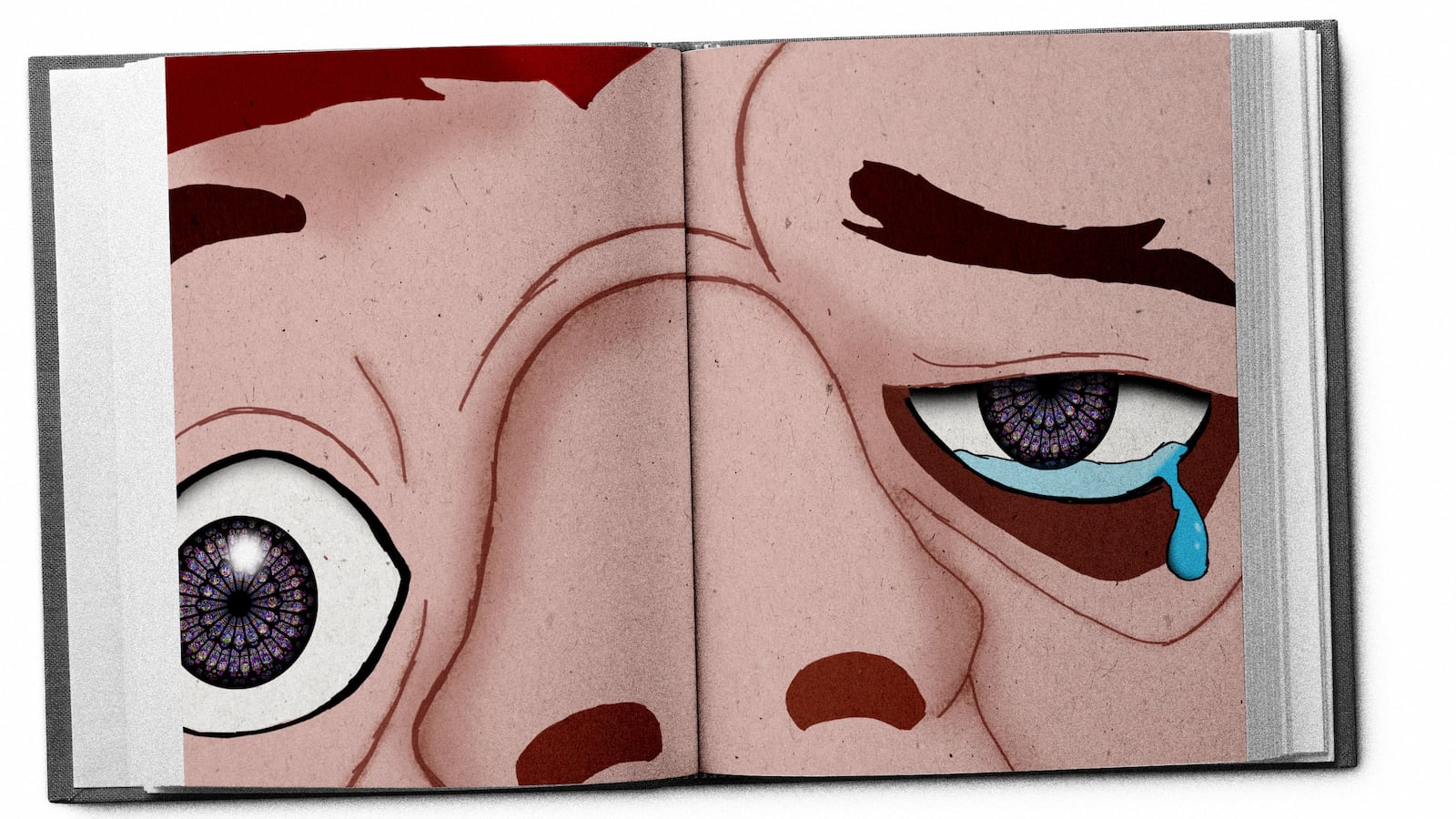

But Hugo laments the treatment of Notre Dame as much as he allows us to despair over Quasimodo’s plight. Think of the cathedral like a great face bearing witness on societal twists and turns. It is the architectural recordist of that which occurs in the streets below, and, in a way, in human hearts encased in chests.

Certainly there were other people in Hugo’s time with affection for the cathedral, if not so much Gothic architecture outright. The passion for Notre Dame stemmed largely from its spiritual nature and French pride, the group-think of “We have wrought this thing, behold.” For Hugo, though, the cathedral was more than a cathedral; it was a symbol, a complex localization of human ingenuity and how humans must think if they are to be ingenious. He also sensed—correctly—that a mighty, prolix novel could be a sharply-honed spearhead. If the novel were a success, Notre Dame was likely to have better days, too.

Buildings have a natural flow to them. Sometimes they flow in circular patterns, other times they appear to flow against their own directional currents. They are like prose that way. The flow of Notre Dame Cathedral is downward—like tears rolling down great stony cheeks. Its movement is towards the folk. Quasimodo receives his castigations in the novel, but not like the urban design committees who allegedly tried to upkeep Notre Dame Cathedral and who made it worse.

“And who put the cold, white panes in the place of those windows?” Hugo writes. The image is that of making a patient with a few bumps and bruises actually sick. These fervid critiques have the quality of Mark Antony’s famed speech in Julius Caesar to them. “And who substituted for the ancient Gothic altar, splendidly encumbered with shrines and reliquaries, that heavy marble sarcophagus…”

Yeah, who! Name names! We’ll get you! Brigands.

Hugo lavished love on the cathedral in swaths of evocative prose. He fairly blanketed it in prose, you might say, every last cornice. And as he connected Quasimodo to this structure, he joined us with both of them.

“His cathedral was enough for him. It was peopled with marble figures of kings, saints and bishops who at least did not laugh in his face and looked at him with only tranquility and benevolence. The other statues, those of monsters and demons, had no hatred for him – he resembled them too closely for that. It was rather the rest of mankind that they jeered at. The saints were his friends and blessed him; the monsters were his friends and kept watch over him. He would sometimes spend whole hours crouched before one of the statues in solitary conversation with it. If anyone came upon him then he would run away like a lover surprised during a serenade.”

That is building with prose right there. That Hugo’s humanism found room for a structure, shows us how enveloping it was. This was one of the first novels to include members from all—or most, anyway—levels of society. You could write about a king, and you could write about a rat in the wall, and you could do so within a single sentence. Charles Dickens and Gustave Flaubert took notice, and I think you see architecture featured so prominently in the work of the former—Scrooge’s house, for instance, is very Notre Dame Cathedral in miniature, and turned inside out—on account of Hugo.

After the publication of The Hunchback of Notre-Dame, parts of the cathedral were renovated, in a manner to gladden the heart of both a Hugo and a Quasimodo. Some of those parts, alas, have just felt the devouring touch of flames. But take heart: art that has existed and made its mark in the world perpetually inhabits that mark and rises within it, just as every great prose work of art surges to the clouds, Notre Dame-style. Don’t be fooled by the flatness of the page. It only feels that way when you rub your hand over it. There is no actual flatness there, when the creator has disassembled expectations.