The walls are closing in on Barry Berkman (Bill Hader), but the tables do eventually turn for the beleaguered hitman—at which point the fourth and final season of Barry gets truly, unexpectedly wonky. Equal parts despairing and absurd, Hader’s serio-comic HBO gem, which returns April 16, remains a one-of-a-kind amalgam of introspective character study, deadpan L.A. crime odyssey, and caustic showbiz satire.

In its last outing, its characters continue to manipulate and betray each other (and themselves) until they’re tangled in agonized knots. Like its tortured protagonist, it’s a show that exists in a state of constant physical, emotional and psychological violence, from which there is apparently—and hilariously, and bleakly—no escape.

Barry definitely hasn’t shaken his brutal past. Acting long ago failed to provide him with liberation, and so too did murdering detective Janice (Paula Newsome) and trying to manage his teacher—and Janice’s boyfriend—Gene Cousineau (Henry Winkler), who discovered that Barry was responsible for her slaying.

That last failure climaxed at the end of season three, as Gene partnered with Janice’s imposing father Jim (Robert Wisdom) to ensnare Barry in a trap that landed him behind bars. It’s in the penitentiary that we now find the Marine-turned-assassin, alone, unstable, and increasingly beset by hallucinations that speak to his fraying mind and sense of self.

In the slammer, Barry is a local celebrity to security personnel because he was on television, which makes them think, “I’m sure you’re not a bad guy!” Barry harbors no such illusions, however, and makes that clear in a premiere-episode confrontation with one guard, which confirms that cruelty is the only real language he speaks, whether he’s punishing others or himself. No one else views Barry kindly at this late juncture either.

Struck by the revelation that Barry committed homicide (while in her company, no less), Sally (Sarah Goldberg) cuts ties with her former beau and flees to her parents’ home in Joplin, Missouri, where she receives little comfort and locates no peace. Gene also, naturally, wants nothing to do with his ex-pupil; answering a call from the inveterate killer—during which Barry asks him, “Are you mad at me? Because I love you”—he simply states, “Hey Barry? I got you.”

Even weirdo Chechen mobster NoHo Hank (Anthony Carrigan), who wants to help Barry, reconsiders at the behest of his boyfriend Cristobal (Michael Irby), given that the two are living a quiet and safe life in the Santa Fe desert. NoHo Hank won’t completely quit on his murderous pal during season four’s early going, thus begetting a cameo from none other than Oscar-winning director Guillermo Del Toro that’s all the funnier for being set up so subtly.

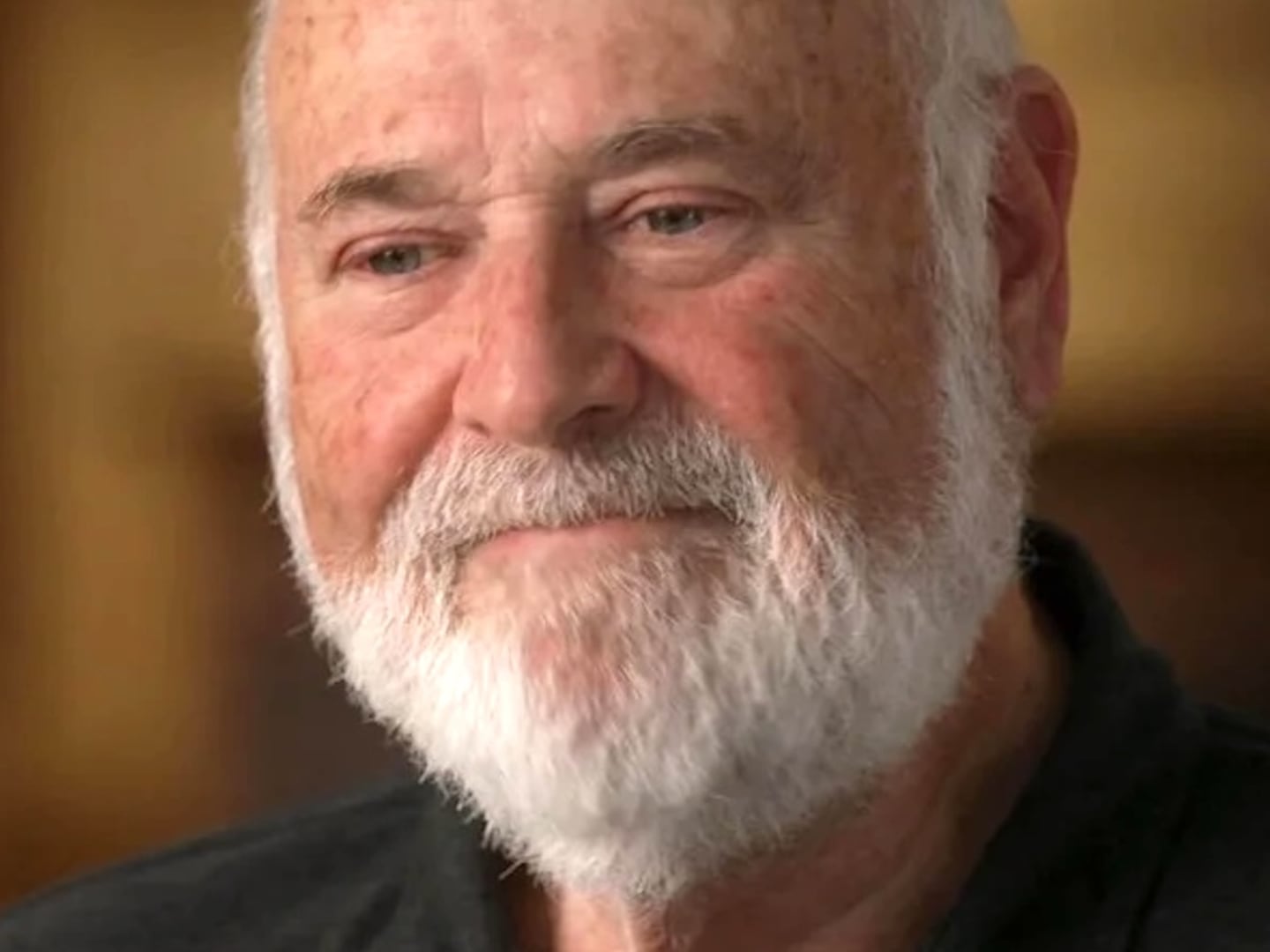

Yet Barry’s more immediate concerns turn out to involve Fuches (a superlative Stephen Root), who happens to be locked inside the same prison, and fears that Barry wants payback for his recent duplicity. Thus, Fuches chooses to strike a deal with the FBI to trade information in exchange for a new life in witness protection—something that, per the show’s formula, not only doesn’t go as planned, but gets flipped on its head in ways that are impossible to predict.

There are numerous surprises strewn throughout Barry’s closing run, including a daring midpoint twist that sends it hurtling crazily toward its conclusion. Since critics only received seven of the season’s eight installments, it’s impossible to make a definitive statement about the saga’s wrap-up. Still, the surehandedness with which Hader orchestrates his material makes the idea of a last-second stumble virtually unthinkable. Few series are as confidently unique as this, and that’s especially true in the present. Helming all eight episodes, Hader solidifies his status as TV’s most accomplished director; his use of extended takes, shifting perspectives, and intricate tracking shots, camera movements, and choreography are remarkable for generating white-knuckle suspense and, as importantly, droll visual humor.

Barry is the rare television effort that’s aesthetically inventive and dexterous—and, moreover, that inherently weds its form to its content. Whether it’s a funny rotating-camera bit involving two people giving a presentation around a Dave and Buster’s private room table, a bravura sequence that fixates on characters fleeing trouble in a car along a winding hillside driveway, or a grief-stricken prison conversation (via phone and through glass) that’s elevated by its POVs’ differing audioscapes, Hader’s technique is a spectacular and vital component of the action’s overarching tone. Just as astonishing is that mood itself: a blend of roiling rage, shame, guilt, hate, desperation, need, and self-loathing that’s expressed via a story about the boundaries between reality and performance, both on screen and off.

As Barry has evolved from a sharp black comedy into an amusingly tormented tornado of misery and mania, Hader’s turn has grown uglier, more volatile, and live-wire, as have those from his supporting cast, who do arguably their finest work in these concluding chapters. Winkler, Root, and Goldberg are particularly phenomenal, with the latter conveying Sally’s complex performative compulsions with a fierceness that one wouldn’t have anticipated at the series’ outset. If Winkler, Root and Carrigan earn the most laughs, Goldberg steals much of the spotlight, capturing her character’s anguish, fury and despondence with the sort of grand-dame virtuosity that Sally herself would envy.

In its watershed fifth installment, Barry fully and breathtakingly digs into the questions that have fueled it from the start. What is the relationship between how you behave and who you (think you) are? At what point does doing bad permanently prevent you from being a good person? Is repentance possible, and if so, what forms can it take? And is lasting change possible, or are our identities (and fates) fundamentally inalterable?

For Barry, the desire to transcend what he’s done, and alter who he’s become, is a quest that constantly brings him back to the same place he most wanted to leave behind, and with an ever-lengthening trail of death in his wake. With a perfectly idiosyncratic balance of gravity and ridiculousness, Hader wrestles with such issues to the bitter, black-and-blue end, transforming his HBO hit into the TV equivalent of a grotesquely funny gaping wound.

Liked this review? Sign up to get our weekly See Skip newsletter every Tuesday and find out what new shows and movies are worth watching, and which aren’t.