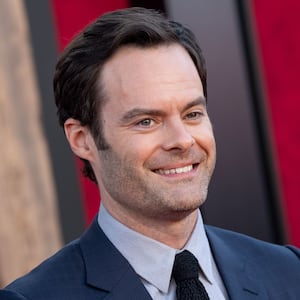

In its first two highly rated seasons, HBO’s dark comedy Barry successfully deconstructed the masculine tropes and glamorized violence audiences have come to expect on prestige television shows about sad, murderous—or generally terrible—men. In Season 3, the multi-Emmy-winning series extends its queries about morality and power beyond Barry Berkman’s (Bill Hader) job as a hitman into other areas, primarily personal relationships where the violence isn’t necessarily physical, and in Hollywood, as Berkman’s love interest Sally Reed (Sarah Goldberg) adapts her one-woman play based on her past abusive relationship into a show.

When we catch up with Sally in the first episode, we immediately see the ways her story has been bastardized and contorted through a Hollywood gaze. For instance, Sally is apparently too old for the lead role she originated in the stage production and is instead cast as the mother to a teenage girl, played by Elsie Fisher, who’s in an abusive relationship. The network executives couldn’t be less engaged with the subject matter. Similarly, Sally’s job as showrunner requires that she be emotionally distant from her past and willing to sensationalize it for entertainment’s sake, like when she approves of an actor slamming a stunt double onto a kitchen table like a WWE wrestling move.

Overall, Sally’s storyline this season is a fascinating and often hilarious case study about the commodification of one’s personal trauma that also manages to skewer the so-called “golden age” of television in the era of streaming and recycled IPs. At the same time, Sally’s already troubling relationship with Barry—she still doesn’t know he kills people for a living—becomes even more problematic when he becomes her abuser (this after trying to protect her from her violent ex-boyfriend last season).

Goldberg, who was nominated for an Emmy for her portrayal of Sally in Season 2 of Barry, credits the skillful execution of these topics to the series’ female writing staff. She notes that showrunners Hader and Alec Berg encourage collaboration when it comes to the female-centric aspects of the show—a choice that’s paid off given that the show’s depiction of Sally and the women she encounters in her career is one of the most superb examinations of female relationships on television.

The Daily Beast spoke to Goldberg about Sally’s experience as a creator, why she’s like Tom on Succession, her relationship with Barry, and how the show expertly portrays power dynamics among women.

You guys obviously had a long break before shooting this season due to COVID. Was it harder to get back into the role of Sally versus going from Season 1 into Season 2?

It’s a great question. I don’t really know the answer. I don’t think so. Before the pandemic hit, we had our first table read, and we were so excited to be back together. And it was that trepidatious moment of, are we hugging? Or are we not hugging? There were rumblings, but nobody knew what was happening. And we all decided to hug. And Henry [Winkler] and I shared french fries, definitely exchanged respiratory drops in the air. And we found we were shut down like the rest of the world. So I think we were just so excited to get back to work that any sort of hesitation around whether or not we could try the characters again was sort of eclipsed by the hysteria and enthusiasm to be reunited and to finally be shooting it. And, you know, all the characters are in a slightly new place this season, which also helped.

I feel like, this season, you guys set out to explore multiple forms of violence outside of Barry’s job as a hitman. Notably, there’s a scene where Barry screams at Sally in front of her co-workers while she’s filming her show that becomes an important focal point of the season. And we learn a little bit about some bad things Cousineau’s done in his past. Was that something Bill Hader and Alec Berg discussed with you?

I think the move into showing verbal abuse and all of that was pretty organic in terms of, if we’re talking about people, morally-bankrupt people making selfish decisions, it naturally lends itself to that realm of violence as well. And I think for Sally’s storyline, it’s really interesting because she’s someone who’s come from a history of domestic abuse.

And what I found interesting about what we’ve done with the Barry-Sally storyline is that when he begins to behave aggressively toward her, she has a trauma response and is quite detached from the reality of what’s happening. And she goes into a historical, rehearsed behavioral pattern, which I found really interesting and moving and an accurate way to tell the story—where we see her in episode two apologizing to him after he’s been verbally abusive to her, and that she’s not waking up to the reality of what’s happening right in front of her. She sort of shuts down. We didn’t take the easy route where suddenly she’s defiant in the moment, and she has all the right words, and she fights back.

Well, speaking of that, in episode 4, Katie, who plays Sally’s daughter on Joplin, confronts her about Barry screaming at her and basically tells her that she deserves better. I was kind of surprised that Sally took Katie’s advice to leave Barry so quickly because she was so eager to brush off the incident. What do you think happened internally that she was able to make the right decision?

I think it’s a combination of things. I think she was in a bit of a coma. And Katie wakes her up. And it’s like she’s in this dream sleep space where she is on some subconscious level seeing and understanding all various behaviors, but she hasn’t gotten to a place to take action. And I think Katie speaking for her—Katie’s her protégée, you know? And she has all the status and power in that dynamic in her mind. And for this young woman who she really admires to hold a mirror up to her so abruptly after the most adrenalized moment of her life—I think it wakes her up.

Sally has a really hard time seeing herself or confronting herself in any way. And this is one of the moments in the entire season where somebody is actually direct with Sally. We don’t see that in the whole show, really. The other actors in the acting class are sycophantic to Sally. Or Barry is always trying to make Sally feel good. [Gene] Cousineau, at times, has been straight with Sally, but that’s often in a self-serving way to his character. So this is actually the first time—and I’m only realizing that as I say it to you—where somebody actually stands up to Sally and says, “Hey, this is what’s happening.”

As an Eighth Grade stan, I have to ask what it was like working with Elsie Fisher. I found Sally’s dynamic with her character to be very endearing.

You’re so sweet. There’s tons of people that have said this because we’re just massive Eighth Grade fans. So basically, when we were at the Critics Choice Awards years ago for Barry, I remember Eighth Grade was up, and Elsie Fisher won. And I was sitting with Alec Berg, and we were like, “Oh my God. That girl—we love her. She’s absolutely incredible.” And Bill and Alec and everybody in the cast were such big Eighth Grade fans. So we basically courted her. We wanted her on the show so badly. And we were just so delighted that she was up for it. And she was there at that table read that we had before we shut down for years. I was worried we might lose her to another project by the time we got back to it. But anyway, she was extraordinary to work with. She’s like 18 and going on 45.

I enjoyed how specific and nuanced the portrayal is of Sally as she navigates the television industry as a female creator, specifically in the streaming era. How much of that was from the brains of the female staff writers? Did you have any input in that part of her arc?

It was a combination. Everything on Barry’s a collaboration, which is a real luxury in television. It was definitely coming from the perspective of our female writers. And for sure, I was bringing some of my own experiences to it. I think we were interested in showing Sally move into a place of success after seeing her in two seasons being an underdog and trying really hard to get somewhere and not having any luck. But what we wanted to show is that, when you get there, it’s not always what you thought it would be. What happens when your art becomes commodified?

And for Sally, she’s at the top of episode 1, when we’ve got that long shot of her walking through her set. She’s literally watching the most horrific moment of her life play out in front of her. And she’s completely pragmatic about, “That looks good.” And she’s totally detached from the emotional story that got her here. And so we were interested in exploring what happens when you walk into that world where commerce and business meets art, basically.

Elsie Fisher and Sarah Goldberg in Barry

HBOI also thought it was very smart and true to life that the executives and higher-ups Sally was feeling disempowered by were other women. I think a less incisive show would’ve had her dealing with these cartoonish Scott Rudin-type figures. And Sally also takes on this girl-boss persona when she’s able to.

I was personally interested in, what do you do when you get a bit of power? And Sally is someone who has been bullied. She has been sexually harassed in the workplace, all of these things. And so when she gets to a point of having some leadership, one would love to see an evolution, and she becomes the kind of leader that she would have wished that she was led by. Unfortunately, that’s not always how human nature works. And I was really interested in modeling her after Tom [Wambsgans] on Succession. I love Tom because he’s such an interesting character because he’s so vulnerable. And you feel so badly for him when he’s being bullied. But the minute he gets even a whiff of power, he becomes the bully himself. So I really wanted to explore that with Sally.

And you also see how fragile the positions are of the women working on Sally’s show when the Barry incident happens, and no one feels like they can say anything.

I think what we wanted to show is how complicated that can be and to look at what happens in the workspace when she’s harassed by her partner, and nobody knows what to do. That line that the writer has, where she’s like, “I really liked my job”—she, like all the characters on Barry, doesn’t choose the right thing to do. She chooses the self-serving thing to do. But you completely understand the predicament that that woman is in. And to me, that scene between the writer and Elsie Fisher is just incredible.

I think they were really, really clever about how they approached that. Just because it’s an all-female network doesn’t mean these are all good people, these are all nice people, these are all maternal people. You know, I’ve been very clear on that, from the beginning, that Sally is the only female series regular on the show, but I never wanted her to be exempt from the moral bankruptcy of the other characters just because she’s the woman. These are all corrupt people. And I didn’t want her to be the morality barometer. The storyline is totally different, obviously, but the decisions that she’s making are parallel with Fuches or parallel with NoHo Hank because they’re sort of self-serving.