In my recent review of Beau is Afraid, I claimed that Ari Aster’s wildly imaginative latest was like nothing he’d ever produced before. That remains true, so long as the discussion is strictly confined to his feature oeuvre. Nonetheless, the origins of his third film are clearly traceable to the eight shorts he helmed before making a splash on the international scene with 2018’s Hereditary—including one that serves as the direct inspiration for Beau is Afraid’s bonkers early going.

Though they’ve never received an official release, Aster’s shorts are available online (the first is on YouTube; the following seven are at the Internet Archive), and when it comes to Beau is Afraid, the most relevant is unquestionably the writer/director’s fourth production, 2011’s six-minute Beau.

Starring Billy Mayo in the title role (which, in Aster’s new film, is handled by Joaquin Phoenix), it concerns middle-aged Beau hurriedly packing his things and leaving his apartment in order to visit his mother, only to be stymied when—while going back to grab the dental floss he forgot—his keys mysteriously disappear from his front door lock, and his suitcase vanishes. From there, anxiety and mania escalate at a feverish rate, replete with neighbors screaming through the walls, a run-in with a knife-wielding intruder, and a distressed phone call to his mom, to break the news that he won’t be arriving as planned.

Aster doesn’t replicate Beau’s every plot point in Beau is Afraid, yet the narrative parallels are obvious and consistent, right down to an individual in the hallway (here played by Aster himself) telling Beau, “You’re fucked, pal!” Even some of the short’s precise compositions and cuts make it into its feature-length counterpart, as does its overarching mood of hysterical panic generated by both external threats (including a creepy possum) and the fear that comes from potentially disappointing your mother.

Beau deviates most noticeably by revealing who stole its main character’s keys (spoiler alert: a beast known as Kolgaan, Collector of Keys?!?). Regardless, Beau is Afraid is of a piece with its predecessor, its stressed-out comedic terror an expansion of the short’s idiosyncratic atmosphere. Here, that’s epitomized by its bizarre and harried protagonist confessing to his mom, “Well, I’m horrified too!”

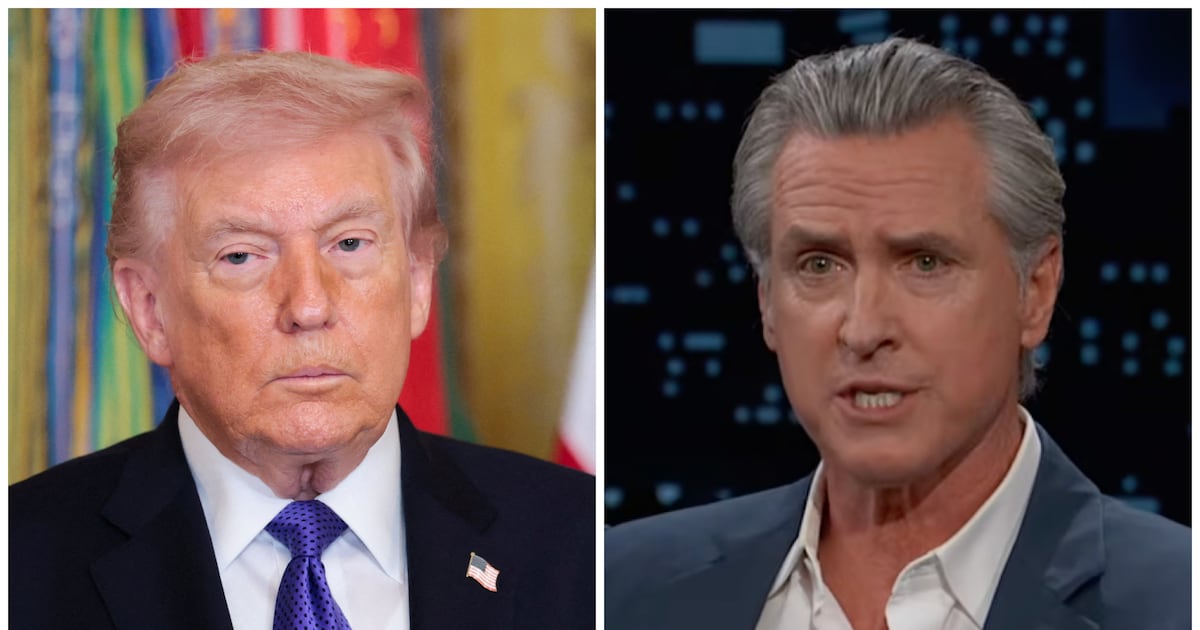

Ari Aster and Joaquin Phoenix on set filming Beau Is Afraid.

Takashi Seida/A24Aster’s other shorts naturally don’t boast such one-to-one links with Beau is Afraid. They do, however, exhibit many of the director’s continuing preoccupations. Fraught mother-son relationships are central to Munchausen (2013) and The Strange Thing About the Johnsons (2011), to the point that both end with moms killing their offspring. The latter also involves a twisted abusive-incestuous bond between father and son that feels like the flip side to the dynamic found in Aster’s new film.

Rather than a dad who’s coveted due to his permanent absence, The Strange Thing About the Johnsons imagines a boy clinging unnaturally (to say the least!) to his ever-present paternal role model. And as seen in Basically (2014), starring a young Rachel Brosnahan (who also appears in Munchausen, alongside Bonnie Bedelia) as an L.A. actress waxing philosophical about her life, career, and religious beliefs, domestic dysfunction is Aster’s beloved stock and trade.

Aster’s initial efforts all balance comedy and horror, but what’s striking is how they frequently favor the former. Basically and C’est La Vie (2016) revolve around characters monologuing caustically, and amusingly, to the camera in largely static tableaus, and The Turtle’s Head (2014), about a sex-obsessed hardboiled detective (Richard Riehle) with a severe case of escalating shrinkage, is fundamentally absurdist in nature. So too is TDF Really Works (2011), a brief, juvenile, rough-around-the-edges infomercial spoof about a new method of expelling gas. Whether successful or not, in each case, Aster leans more heavily into humor, even though his Lynchian instincts (particularly in 2008’s Herman’s Cure-All Tonic and Munchausen) provide the action with a bitter, unreal, malevolent edge.

Unsurprisingly, Aster’s shorts are inherently showcases for his abilities, which improve over time. Be it the dialogue-free Munchausen and fourth wall-breaking Basically and C’est La Vie, or the melodramatic The Strange Thing About the Johnsons and the genre-spoofing The Turtle’s Head, these small-scale ventures play like demo reels for his various formal, narrative, and tonal skills. That evolution is unmistakably aided by Aster’s partnership with cinematographer Pawel Pogorzelski, who shot five of the director’s eight shorts (and has assumed likeminded duties on his three features), and whose sharp, evocatively lit visuals have become one of the A24 auteur’s signatures. The ominous pans, meticulously composed, deep-focus images, and unnervingly sharp edits of Beau is Afraid are all present in the duo’s maiden collaborations, if in lesser degrees.

The only Aster trademark missing from these developmental works, in fact, is his goriest: severed and/or obliterated heads. Still, throw in Munchausen’s embroidered title card (shades of Midsommar), and the seeds of Aster’s films aren’t hard to discern. As such, these shorts are fascinating windows into the formative process of an artist who, with Beau is Afraid, is finally carving out a unique niche of his own.