There was a time that Lana Wilson was the most in-demand filmmaker in Hollywood.

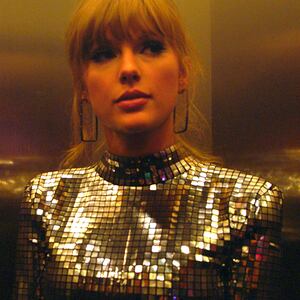

The documentarian, whose big break came with 2013’s After Tiller, most famously directed Miss Americana, the headline-making 2020 portrait of Taylor Swift at a time in her career where she finally felt emboldened to speak out, be candid about the toll of fame, and get political.

Soon after Miss Americana had a roof-blowing Sundance Film Festival premiere and then streamed on Netflix, an entire red carpet’s worth of celebrities lined up at Wilson’s door, asking to receive the same treatment.

“There are many I said no to, believe me,” Wilson told The Daily Beast’s Obsessed. Asked to share who they were, she raises an eyebrow and stares back, as if to say, “You knew before you asked that I was never going to answer that,” and lets out a long sigh.

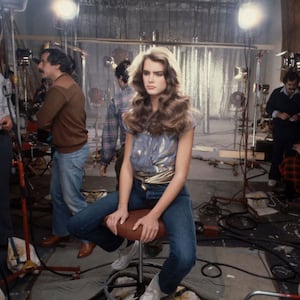

But then Wilson did say yes, to Brooke Shields. And now, we were in Park City at the first in-person Sundance Film Festival since the pandemic, days after the premiere of Pretty Baby: Brooke Shields, a two-part documentary in which the actress recounts the pivotal moments of her life in the spotlight as she works to recontextualize and learn from how she was exploited by Hollywood.

The film chronicles Shields’ career from the time she began modeling as an 11-month-old in a soap ad. It reveals the way in which she was sexualized and exploited as a young actress, and how she’s spent her entire life reckoning with the trauma caused by the industry. In one emotional segment, she publicly discusses for the first time an alleged sexual assault by a Hollywood filmmaker.

Pretty Baby reveals how Shields had managed to transform herself many times over, overcome the expectations had for her, and finally understood her identity and the power of her own agency. “When you watch the film, living Brooke’s life with her, I hope you're feeling it with her emotionally,” Wilson says.

Here, Wilson reveals what convinced her that a documentary about Shields would be worthwhile, the considerations and concerns over including the sexual assault admission in the film, and the urgent contemporary message that she hopes audiences will take away about how we still treat women and their sexuality.

What was it like to watch the film alone with Brooke for the first time?

I feel like I keep using the word intense, but a lot of things about this project are intense. It was just me and her. I think it was very overwhelming for her. I think she had always looked back in her career and had seen it in a very compartmentalized way, which you can understand. Like, how does all of this connect? I think it is very overwhelming, first, to go through decades of material, but also to see this thread through it. That's what I was really focused on, finding what is the central thread of Brooke’s story? What is the evolution she went on? Seeing that in a single setting was very overwhelming for her—very emotional, very surprising.

There are obviously different approaches to documentary filmmaking. One is to spend years diving into a passion project. The other is how this happened, which is someone comes to you with an idea. What is it like to come into a project when you hadn’t been noodling on it for a long time prior?

You look at what it is, and what’s there. And what’s possible. Even if something is being brought to you and even if it isn’t years of independent work. For me, I still know I’m going to have to give 2,000 percent of myself to it. So you ask, is this rich enough to live in for a long time? Will this be surprising, and challenge me in new ways as a filmmaker? With this, I was uncertain about doing another project about a major celebrity. I’m not personally very interested in what it’s like to be famous.

After having just done Miss Americana with Taylor Swift?

Yeah, exactly. But both of these people, these are two remarkable human beings who have a lot of layers to them and a lot of richness. I think that, with Brooke, I loved the idea of doing a mostly archival project, which is something I haven’t done before. I started to look at the archival materials on this hard drive she gave me. This was before I signed on. I met her. I knew she’d be incredibly smart and funny because I’d read her books. But then I got the hard drive, and I started looking at the material. I could just see where we could live in this material.

What excited you about the archive?

I saw this little girl being told, “You’re beautiful, you’re sexy, you’re so mature, you’re gorgeous..” People are praising her on the one hand for that, but then also sometimes saying, “You’ve gone too far, it’s exhibitionist, aren’t you ashamed of this?” That just reminded me so deeply of what is still going on for girls and women, where you’re taught that.

Still, I think that the most important thing is for you to be desirable, to be hot. And we see women primarily celebrated, still, for being sexually desirable. At the same time, if they go too far, if they cross some kind of invisible line into sluttiness, they’re condemned. They’re blamed for anything that happens to them. They’re shamed. So then the idea came up of, well, what if we tell Brooke’s story, but are also using her as a vessel for a bigger conversation about women and girls in a way that feels really contemporary?

The last time I was at Sundance, you were premiering Miss Americana with Taylor. Now we’re finally back again and you’re here with Brooke, so I think a lot of people are probably trying to draw connections between those two films. Is there something that you think you learned from spending time doing Miss Americana and getting to know Taylor that maybe helped instruct how you approached a Brooke Shields project?

I do think that fame can amplify problems that everyone has. That was something that I was really struck by making Miss Americana. I remember being so surprised by Taylor voicing some of her internal struggles and thinking, wow, this is very relatable. Everyone goes through this. That film was about capturing more of a singular moment in time for her at this pivot point in her life and her career, where she was re-evaluating how she was living and letting go of this idea of making everyone happy. She was kind of coming to this realization that you can’t make everyone happy with you, so, therefore, how am I going to live and be? With Brooke, it’s more of this evolution over decades.

The evolution over time is really striking in this film.

It’s a very different journey and dealing with very different issues. But I think what is similar is that Brooke had this experience where being famous was greatly amplifying issues and problems that a lot of girls and women experience, but on steroids. Being objectified as a girl, being sexualized, individuating from your parents, having relationships, starting a family of your own—Brooke experienced all of these things, but in this hyperdrive way.

It was on a scale that no one had experienced before, really.

While she was trying to figure out who she was as a person, she was also this symbol for millions and millions of people and an object for millions and millions. In a weird way, she was an object and a symbol before she was a human being. We’re all mostly trying to figure out who we are our entire lives. But for Brooke, it was extra hard because she had people telling her who she was, and the type that she was, and that changed at different times. Imagine being a child and becoming conscious while you’re already a symbol. That’s really unique, and that’s very different from what Taylor experienced.

A major moment in the documentary occurs when Brooke discusses her sexual assault. It is something that is obviously headline-making, but I wonder if there was concern that it would become the focus and the only takeaway of the film. Did you or Brooke have any concerns about that?

Yes. She told me about it really early on. To me, that alone indicated that this was something she was ready to talk about and wanted to talk about. We did talk about that, at the start: Would this be so much of a headline that it would detract from the entire project in a way? I was like, let’s just talk about it. Let’s do the interview. Let me go into the archive. And let’s see what happens. I was like, I don’t think we should have it in there unless it's part of the story cohesively. We don’t want some standalone news item for no reason. But I had a feeling from the beginning that it would be a part of all of the themes of the film.

It does connect really powerfully to those throughlines that we had discussed.

It’s an important moment in her life, but it is also the ultimate violation of her autonomy—bodily, mentally, emotionally. So when she’s going through this process of trying to gain autonomy, this is a huge event and a turning point in her life. I felt that once it was in it, I couldn’t imagine the documentary without it. But I always told Brooke, if you change your mind, I’ll take it out.

That was the one scene that I showed to her before I picture-locked to make sure she was totally comfortable with what was in it, because that was really important to me, too. Because I think that healing from a sexual assault, a big part of it is regaining autonomy and control. And a part of that is in being thoughtful about how you tell your story and when and making sure it’s on your terms.

And it seemed like, at least the way that it plays in the film, that she was aware that it was going to be a thing that people were going to turn into news. It’s almost as if she was consenting to it now being a major news story, which has to be a hard place to arrive at.

Yeah. She was very much aware of that. I think that it came through, and that, talking about her life, this was an important part of it. But also, I think it’s in line with, you know, what she did with her book on postpartum depression, for example. She talked about something really difficult, but knew that that could be comforting for other people who are going through something similar. What I appreciated about the way in which she talked about her sexual assault was that it’s not simple. It’s really complicated. And it’s something she struggled with for a long time.

She does speak really powerfully about how complicated it is.

I love how she verbalizes that in a way that I’ve rarely heard it talked about before, because I think that saying stuff like, “I didn’t fight that hard. I was afraid I was gonna get choked out.” That alone is really powerful, because I think there’s an assumption sometimes that it’s fight or flight if you're going through sexual assault. But, actually, freezing is by far the most common reaction of anyone experiencing sexual assault. And hearing that from someone like Brooke Shields can be really powerful. She was really aware of that.

I was obviously really moved by that. But in a way that really surprised me, I was also very moved by the family dinner scene at the end, when her daughters and her have a frank discussion about the films she starred in as a kid that would be inappropriate now. I’m curious what that meant to you to film.

Near the end of filming, it was basically just like, “Can we film you and your family having dinner? To show you now as a parent of daughters?” Obviously her relationship with her mother was such a huge part of her life and identity. And then everything she went through to have kids. And now here she has a family of her own. I remember we got in there, and I just thought it might be a slice-of-life moment. I said right before dinner, “Have you seen any of your mom’s films?” And then they started talking. Brooke told me later,”I don’t think we would have talked about any of that stuff, if you hadn’t been there.” That ended up being a perfect ending.

Keep obsessing! Sign up for the Daily Beast’s Obsessed newsletter and follow us on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and TikTok.