Directed by Sean McNamara, the artist behind 3 Ninjas: High Noon at Mega Mountain, Cats & Dogs 3: Paws Unite, and Baby Geniuses and the Treasure of Egypt and its follow-up Baby Geniuses and the Space Baby, Reagan lives up to its creator’s illustrious canon.

Describing this two-hour, 20-minute film (which has been sitting on the shelf for close to four years) as a hagiography is to understate its fawning celebration of its subject, who’s presented as not merely a charismatic actor and effective statesman but as God’s chosen warrior in a titanic battle between good and evil. Regardless of how you feel about Ronald Reagan the president, most will be united in finding this biopic a preachy, plodding, graceless groaner.

Reagan, which hits theaters Aug. 30, begins with the March 30, 1981, attempted assassination of the newly elected commander-in-chief by John Hinckley Jr.—a calamity that’s preceded by Reagan telling an AFL-CIO conference, “Our destiny is not our fate. It is our choice. You and your forebearers helped build this nation. Now help us rebuild it.” Left out of this scene is Reagan’s “Make America Great Again” remark, no doubt to avoid drawing parallels between its protagonist and Donald Trump, and it’s the first of innumerable instances in which McNamara and screenwriter Howard Klausner warp history for one-note lionization.

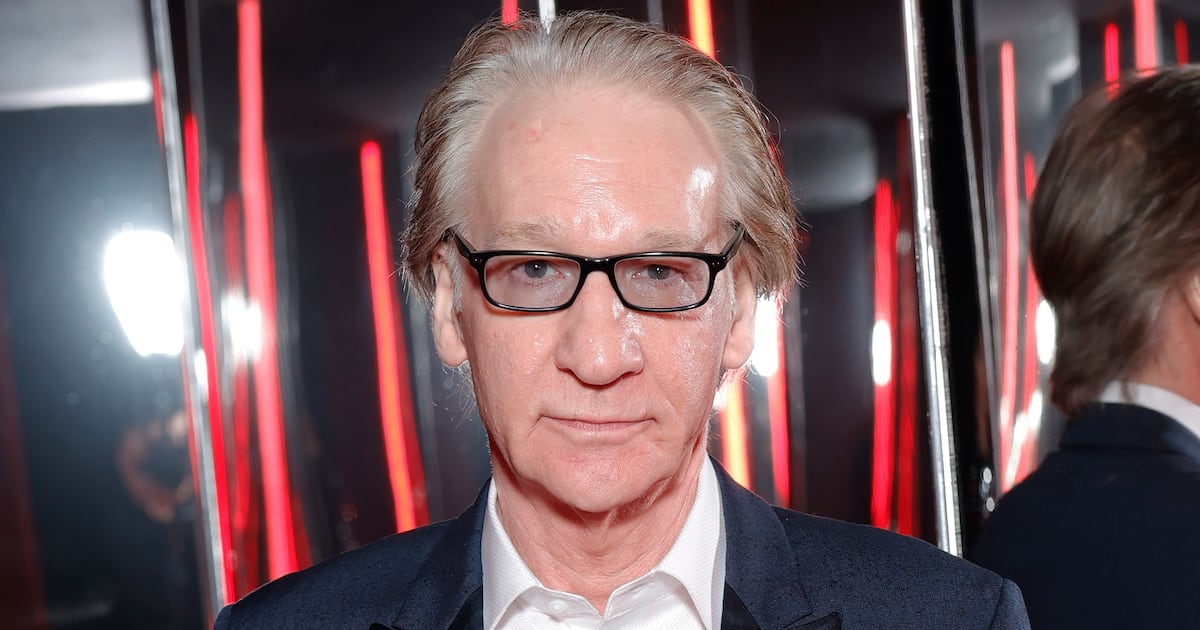

In narration, the Gipper (Dennis Quaid) remarks that this near-death experience is part of a “divine plan,” at which point Reagan establishes its present-day framing narrative, in which a promising young Russian politician (Alexey Sparrow) visits former spy Viktor Petrovich (Jon Voight) to hear about the legend of the 40th president.

This involves Voight affecting a hilarious Russian accent (as when he refers to “da Hollywood glitz and glamoor”) and, in flashbacks, wearing a fake beard that’s as dark as his awful dye job. His performance is no more subtle, dominated as it is by faux-sage pronouncements about how he knew that Reagan was the Soviet Union’s most formidable adversary—they called him “The Crusader!”—and his laughably fearful reaction-shot expressions whenever the president makes a speech or move that challenges the USSR’s ambitions.

Reagan subsequently rewinds to 1922 Dixon, Illinois, where adolescent Reagan (Tommy Ragen)—known by his childhood nickname Dutch—hones his public speaking skills at the First Christian Church and abides by the pious teachings of his devout mother Nelle (Amanda Righetti). Reagan’s dad Jack (Justin Chatwin) is a drunken lout but Nelle is sure that God has a purpose for her son, and he starts to discover what it is while a teenage lifeguard (David Henrie).

At this job, Reagan realizes that he’s a natural charmer with the ladies and learns how to foresee trouble by watching the currents beneath the surface. He’s also a football player who brings two Black teammates home to stay with his family, although healing racial tensions aren’t his true calling—defeating communism is, as he understands after attending a speech by a Soviet defector who talks about how the USSR denied its people their churches.

By the time he arrives in Hollywood, he’s embodied by Quaid, and the sight of the 70-year-old actor trying to play a thirtysomething Reagan is about as awkward as it sounds. Such clunkiness is omnipresent in Reagan, whether it’s Reagan cornily fighting communist labor leader Herb Sorrell (Mark Kubr) on behalf of Jack Warner (Kevin Dillon) and the Screen Actors Guild—Sterling Hayden dubs Reagan “a one-man battalion against this thing!”—or sharing a strained meet-cute in his office with future second wife Nancy (Penelope Ann Miller).

Riding horses together, Reagan confesses, “I just want to do something good in this world. Make a difference.” He figures out how to do just that by entering politics—a natural evolution according to Nancy, who expounds that, thanks to reading books about communism, espionage, and Eastern Europe, he knows more about politics than Nixon and JFK!

Reagan’s governorship and two terms in the Oval Office are dramatized with similar hokeyness, such that Reagan resembles a TV movie from the era of its subject’s presidency.

The simplistic and sentimental sermonizing never ends: Pat Boone plays a reverend who prophesizes that Reagan will be the leader of the free world; Nancy surmises, “You just may need to save us;” and Reagan rails against higher taxation and nuclear proliferation, all while simultaneously taking a tough stand against Mikhail Gorbachev (Aleksander Krupa). Opposition to Reagan’s first term is encapsulated by a brief montage of non-fiction footage set to Genesis’ “Land of Confusion,” but this is just a means of setting up his eventual re-election win against Walter Mondale, after which he proceeds to keep kicking Soviet butt, most notably by demanding, “Mr. Gorbachev, tear down this wall!”—a moment cast in effusively triumphant terms.

Reagan briefly skims past the Iran-Contra scandal, which Reagan handles by “doing what you do best—tell them the truth.” Reagan doesn’t prove that honesty is its main character’s strong suit, per se, but that’s beside the point; McNamara is only interested in suggesting that, at every turn, Reagan was a staunch defender of down-home American (and Christian) values, and instilled respect in his allies—such as Margaret Thatcher (Lesley-Anne Down), who exclaims “Well done, cowboy!” after his Berlin Wall remarks—and terror in his adversaries.

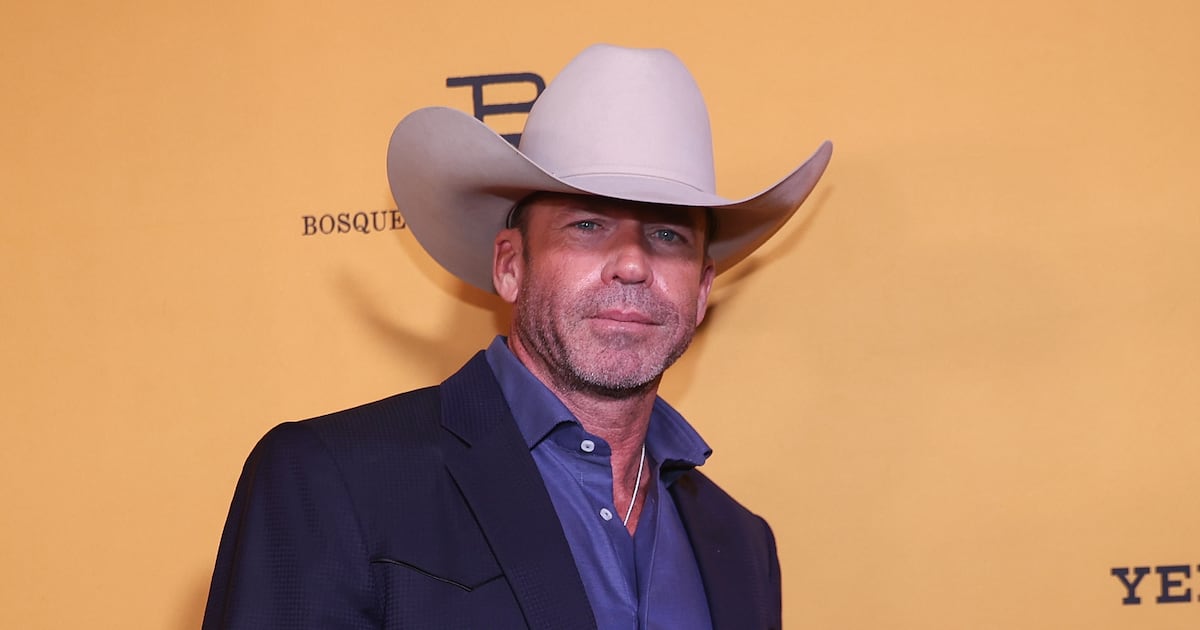

Dennis Quaid and Penelope Ann Miller as Ronald and Nancy Reagan

ShowBiz DirectNonsensicality abounds, never more so than in Petrovich’s explanation for Reagan’s success: “People will not give their lives for power or a state or even ideology. People give their lives for one another, for the freedom to live those lives as they choose, and for God. We took that away. The Crusader gave it back to them.” Good luck separating truth from slop in that whopper.

Considering its ceaseless hero worship, it’s unsurprising that Reagan concludes with an Alzheimer’s-afflicted Reagan riding off into the sunset. Yet for all the effort it expends trying to sell the late president as the embodiment of American virtue, McNamara’s film is so ungainly and transparent that it plays like embarrassing propaganda.

Alternating between folksy charm and noble resolve, Quaid’s superficial turn is painfully unconvincing, and everyone else (including Creed frontman Scott Stapp as a blink-and-you’ll-miss-him Frank Sinatra) appears to be acting as if they’re in a parody of an old-timey biopic. “Say what you mean and mean what you say,” advises Reagan. That’s easy to do: Reagan is a historic dud.