Selecting one film as the greatest of all time is a foolhardy endeavor destined to inspire spirited debates (if not hostile arguments) that can never be definitively resolved. Diverse and multifaceted, art resists such narrow hierarchical quantifications, and yet that won’t stop amateurs and professionals alike from trying to fit dissimilar works into ranked lists, the most noteworthy of late being the eighth iteration of Sight and Sound’s once-a-decade movie poll.

Culled from the ballots of more than 1,600 participants, the magazine’s rundown is an overarching macro-byproduct of many unique micro-submissions. Consequently, it’s less an authoritative declaration of distinction than a snapshot of critical consensus circa 2022 and, by extension, a glimpse at the way attitudes and opinions have shifted over the past 10 years.

And as this year’s poll proves, shift they most certainly have, generating a not-inconsiderable bit of controversy in the process.

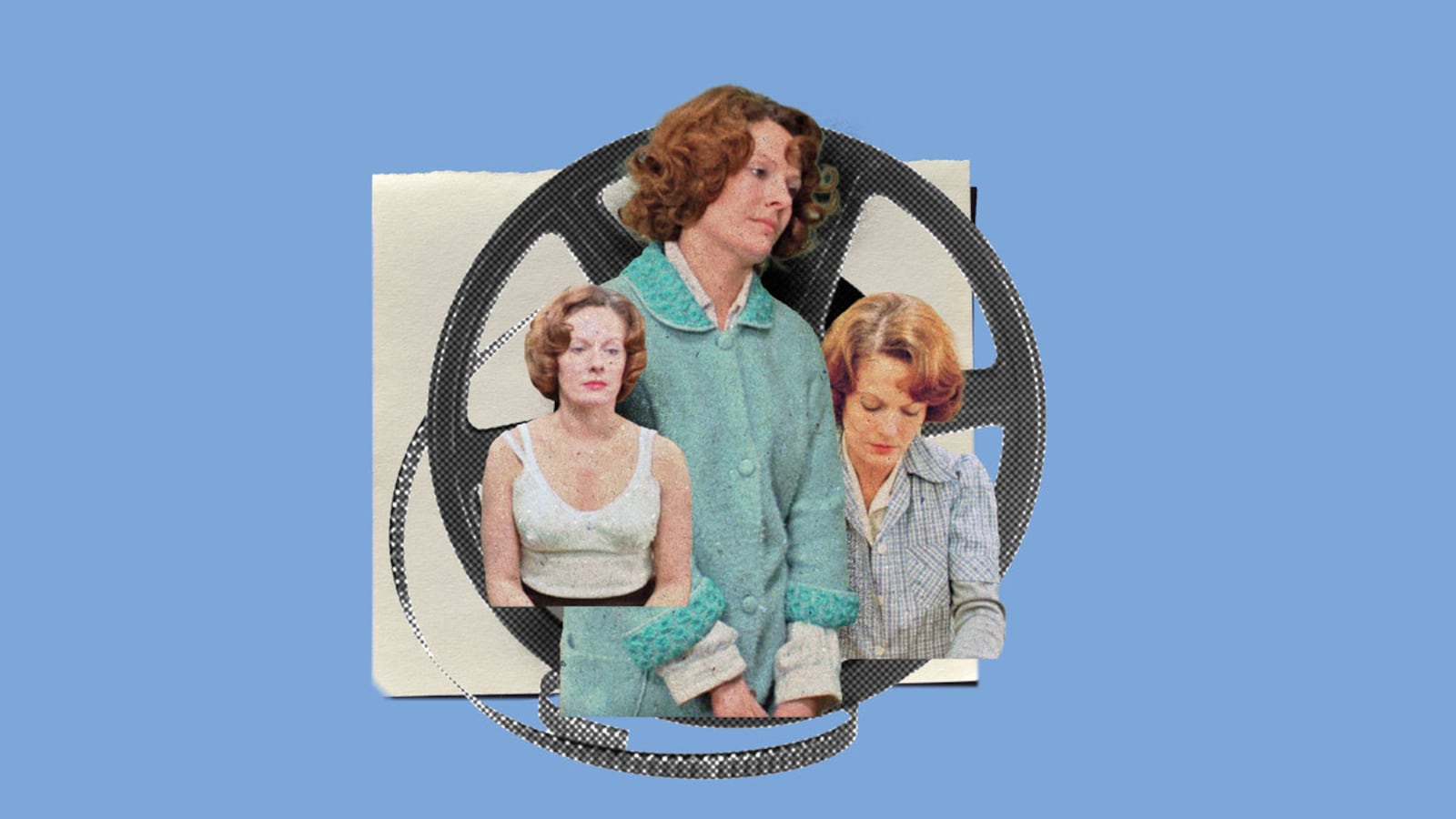

Whereas prior Sight and Sound surveys have been led by hallowed standby Citizen Kane and, in 2012, by Vertigo, this year’s result featured a shock at the top: Jeanne Dielman, 23 quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles, Chantal Akerman’s groundbreaking 1975 drama about the day-to-day drudgery of a widowed homemaker. A 201-minute Belgian film that boasts little mainstream recognition and, likely, even less appeal, it was a surprise that virtually no one saw coming—especially since it had only placed 36th in 2012 and received a scant four critics votes in 2002.

Cheers, jeers and much in-depth analysis has ensued, with little universal agreement struck, save for the persuasive notion that Jeanne Dielman’s ascension is due to a younger and more varied voting body whose tastes skew modern—a fact borne out by increased representation of female and Black filmmakers.

There is, as everyone knows, no way to conclusively contend that Jeanne Dielman—or any other individual cinematic offering—is the medium’s apex achievement. Nonetheless, the recent slander thrown at Akerman’s film in some quarters (It’s boring! It’s niche! It’s woke!) is unwarranted to the point of absurdity. From the moment of its premiere, Jeanne Dielman has been rightfully hailed as a pioneering masterpiece, and it’s one that affords a portrait of female marginalization, subjugation, and suffering that’s as strikingly empathetic and relevant today as it was in 1975.

Jeanne Dielman tells the tale of its title character (Delphine Seyrig), who resides in an upper-floor Brussels apartment with her teenage son Sylvain (Jan Decorte). Jeanne’s life is defined by routine: mornings spent brewing coffee (much of which is stored in a giant thermos) and shining Sylvain’s shoes; afternoons taken up with shopping and cooking; and evenings marked by meals with her lone child, after which they respectively read and knit.

It’s an existence of oppressive quiet—Sylvain barely speaks to his mother, except for immediately before going to sleep—and even more crushing mundanity. Even Jeanne’s method of earning a living—by working as a prostitute for regular daily clients who appear and disappear at her front door—is merely another chore to be handled with dutiful stoicism.

Seyrig’s face is a placid mask, its pleasant inexpressiveness concealing a wellspring of unhappiness. Jeanne Dielman simply watches its subject as she goes about her humdrum customs (peeling potatoes, washing dishes, taking baths), cocooned in silence and isolation. Akerman routinely frames her protagonist in constricting doorways and hallways, and in mirrors that provide opportunities for self-reflection.

She composes her drama with static set-ups in which her camera never moves, and only slightly deviates from its collection of fixed vantage points; sharp edits are the means by which the proceedings progress forward. It’s an aesthetic that’s highly attuned to Jeanne’s confining inertia and weighty misery. Moreover, its manicured nature—amplified by a soundscape comprised of natural sounds as well as the hiss of the audio track itself—calls attention to our own presence as spectators of this generally private, unseen domestic scene.

Jeanne Dielman is a window into a world hidden from male (and professional) society, and defined by rigorous repetition and estrangement. Abandoned by the death of her husband, barely looked at by her entitled son, and treated as a sexual commodity by her customers, Jeanne is a woman subtly used and abused. She’s truly alone, and Akerman’s fixed gaze and unswerving consideration elicits empathy for her tedious and thankless life. In doing so, it also generates outrage on behalf of her and all those who endure similar monotonous fates. Beneath its ordinary and tempered façade, Jeanne Dielman simmers with feminist indignation at a socio-cultural paradigm that relegates so many to exploitation—or, as evoked by Jeanne’s mechanical movements and passive countenance, to live as obedient automatons.

Form and content are both quietly revolutionary in Jeanne Dielman, its approach as radical and uncompromising as is its compassionate contemplation of Jeanne. By fixating on the commonplace nothingness of Jeanne’s every waking hour, Akerman provokes intense engagement, such that when minor deviations in the character’s routine materialize—a dropped piece of silverware; an overcooked pot of potatoes—they resonate first as jarring ripples, and then as seismic fissures. Disruption comes in minute form, most pointedly via a missing button from her coat that she doggedly tries to replace at numerous shops—an attempt by Jeanne to literally and figuratively keep things together, and as they formerly were. Once cracks in her reality emerge, however, they turn out to be irreparable, growing wider and deeper until things culminate in a final act of violence that’s equally spontaneous and inevitable.

Akerman tells Jeanne’s tale in real time and in fragments, the latter escalating as she drifts from her proscribed cook-bathe-screw-knit path until, ultimately, she seems to be spending entire nights away from home. Those gaps are ours just as they are hers, and they function as gnawing, obliterating voids at the heart of Jeanne Dielman. Akerman closes the film on a lengthy unbroken shot of Jeanne contemplating her actions and its ramifications at the dining table, her face segueing from faint contentment to consuming despair and back again. Nothing is said but everything is conveyed; it’s easy to imagine the winding rollercoaster course of her thoughts as she sits by herself, her past, present and future colliding in the dark.

In its kindhearted regard for this woman, imagined by Akerman as both an archetype and a complex individual, Jeanne Dielman feels as fresh, alive and bracingly bold as ever. Whether it’s the best, or the second-best, or the fifth-best, is impossible to determine and completely unimportant. It’s capital-g Great, and any serious cinephile who hasn’t yet sought it out is only cheating themselves.