What’s a heavyweight cast like that—Bobby Cannavale, Rose Byrne, Robert De Niro, Whoopi Goldberg, Vera Farmiga, Rainn Wilson from The Office—doing in a melodramatic misfire like this?

Ezra has its heart in the right place, but that’s the best that can be said about Tony Goldwyn’s strained family drama, which lacks trust in the intrinsic power of its depiction of parents raising a 11-year-old who is neurodiverse, stacking the audience’s sympathies with a manipulative story of parental abduction, cross-country road trips, and Jimmy Kimmel Live, squandering goodwill as it goes.

Cannavale stars as New York comedy writer Max, who’s pursuing a career in stand-up but can scarcely get through his sets at the Comedy Cellar without self-sabotaging. That the jokes we hear him deliver are the types of groaners you’d never expect to leave the safety of a writer’s notepad (“I met my inner child, and he had a gun”) is par for the course with a character who’s at the mercy of his own compulsions, either oblivious to his impact on others or unable to get out of his own way.

Max struggles to connect with Ezra (newcomer William A. Fitzgerald), the son he shares with estranged ex-wife Jenna (Byrne), even as he rejects out of hand the suggestion that anyone else knows the best way to reach his kid, who’s been acting out at school. When, at a parent-teacher conference, Ezra’s teachers discuss their recommendation that he be medicated and sent to a special-needs school, Max reacts at first angrily then violently, even assaulting the principal in his response to the idea that his son might be out of control. After Ezra becomes distressed and ends up in the hospital, Max again loses his temper and winds up in jail for the night, putting his ability to see his son at risk.

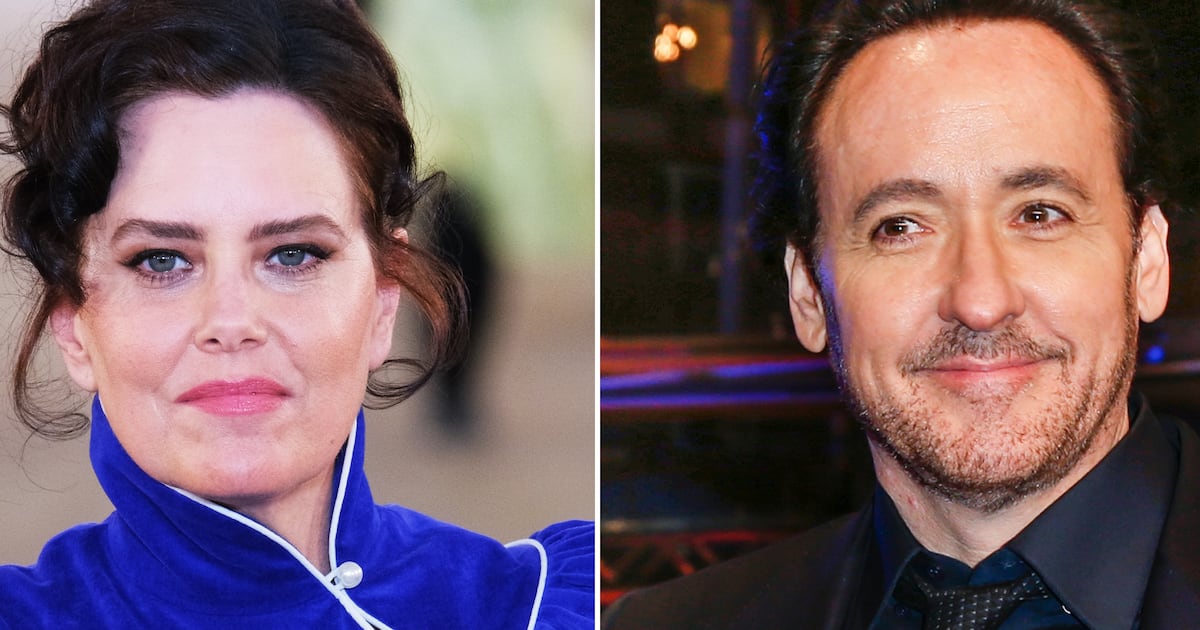

Robert De Niro, Bobby Cannavale, William A. Fitzgerald

Bleeker StreetAnd so Max makes another rash decision, absconding with Ezra and traveling from New Jersey to California, where he’s landed the opportunity to audition for Kimmel. Along the way, he hopes he’ll be able to bond with his son and reach a deeper understanding of their relationship, even as Max’s father, Stan (De Niro), joins Jenna—and, after she reports what happened to law enforcement, a handful of police officers—in setting out on the road to track them down and bring Ezra home.

In mainly centering his story on the relationship between Max and Ezra, screenwriter Tony Spiridakis (who drew upon his firsthand experiences of raising a child on the autism spectrum) captures the beautiful chaos of parenting but devotes as much time, if not more, to Max’s personal journey toward accepting both his son and himself.

Your mileage may vary with Ezra based on your ability to get on board with Max as a character. As wonderful as Cannavale often is in the role, summoning great depths of anxiety and helpless emotion to the surface in seconds, the character’s reckless endangerment of his son starts early and seldom lets up. But the filmmakers are committed to getting you on Max’s side, often at the expense of common sense; when their road trip leads them to old friends, played first by Wilson then Farmiga, Max jovially informs them he’s on the run from the police and is rewarded for his honesty, with both warmly advocating that he’s in the right for taking his relationship with Ezra into his own hands.

Jenna, meanwhile, is berated by just about every other character in the film, especially Stan, for her role in making it harder for Max to see Ezra. Stan even goes so far as to exclaim that she’s responsible for making Max kidnap his son; when he eventually catches up with Max, it’s not to talk sense into him but to weepily apologize for his own failings as a father, a scene that De Niro handles with more poignancy and grace than it deserves.

It should be said that Fitzgerald, an actor who is on the autism spectrum, is Ezra’s best defense against its story’s more histrionic impulses. At once wise beyond his years and wildly impulsive, Ezra is a chaotic source of energy in his parents’ lives, as likely to spout extensive movie quotes from memory as he is to blurt out the punchline of Max’s set before he has time to deliver it, and Fitzgerald brings the character off the page with an immediate confidence and attention to detail that extends to his easy, believable chemistry with Cannavale.

It’s just a shame that these performances, all well-meaning and delivered by pros, are trapped within such a contrived, thinly sketched outline of a film. Ezra tugs clumsily at the heartstrings. It would take a heartless cynic not to be moved by small beats in which fathers and sons envelop one another in tender embraces that say more than their words ever could, just as it would take a total sap not to resent the strain of mawkish sentimentality that pervades most everything else on screen.