Following their 2019 superhero blockbuster Captain Marvel and ensuing prestige-TV efforts Mrs. America and Masters of the Sky, writers/directors Anna Boden and Ryan Fleck go back to their roots with Freaky Tales, a nostalgia-drenched saga that’s steeped in Fleck’s childhood memories of growing up in the Bay Area in the late ’80s, and which serves as the opening night selection of this year’s Sundance Film Festival, where they initially got their start. On the basis of the duo’s latest, however, you can’t go home again—or, at least, you can cut-and-paste all your adolescent obsessions into a giant collage (and recruit Pedro Pascal and Ben Mendelsohn to participate in the madness), but that doesn’t mean it’ll amount to more than a messy, insubstantial grab bag of your favorite things.

A film about underdogs that doesn’t wear its influences on its sleeve so much as scream them in your face, Freaky Tales opens with VHS static, warbling music, old-school computer graphics and a classic video game introduction that establishes 1987 Oakland as a place with “electricity in the air.” It’s additionally reigning down from the sky via lightning bolts and coming out of some individuals’ eyes courtesy of Golden State Warriors guard Eric “Sleepy” Floyd (Jay Ellis), who when not playing the Los Angeles Lakers in the NBA Playoffs is running the Psytopics Learning Center, where he’s teaching men and women to harness “cosmic life force” and use their minds to vanquish internal and external enemies. Imagining Floyd as a quasi-supernatural guru is merely the first of numerous instances in which Boden and Fleck swirl fact and fantasy, although as quickly becomes apparent, there’s nothing especially inventive about how they combine their disparate ingredients.

Split into four chapters that eventually crisscross in ways that don’t suggest Robert Altman so much as any number of ’90s-era Tarantino counterfeits, Freaky Tales commences with a clash between ska punks and neo-Nazis at a music club not far from the Grand Lake Theatre, where Tina (Ji-Young Yoo) and Lucid (Jack Champion) have just seen The Lost Boys. Tina and Lucid are injured in this melee and, afterwards, they and the other members of their close-knit community decide that they must fight back against these ruthless hatemongers. Thus, channeling the spirit of Walter Hill’s The Warriors (which will subsequently be referenced again), they fashion homemade weapons and wage war against their white-nationalist adversaries in a street clash that’s marked by copious bloodshed and the same type of line-drawing cartoon embellishments (“Boom!”) that were previously employed to illustrate Tina and Lucid’s dreams and feelings for each other.

Watching Nazis take it on the chin (and in the jugular) is always satisfying, yet unlike the truly nightmarish Green Room, Freaky Tales casts such material in shallow wish-fulfillment terms. Drearier still, it revisits that same well during its closing installment about Floyd’s vengeful rampage against related skinhead scumbags (including the late Angus Cloud). In that episode, Floyd’s historic night on the court opposite the Lakers, culminating in a 29-point fourth quarter, is marred by a crime and tragedy that compels him to wield his mystical abilities to get payback. John Carpenter and Enter the Dragon figure prominently here, albeit without much in the way of flair; for all the super-slow-motion, choreographed martial-arts moves, and gruesome dismemberment, it’s an homage that feels well past its sell-by date.

Unfortunately, homage is primarily what Freaky Tales has on its mind. In its second part, Boden and Fleck concentrate on Barbie (Dominique Thorne) and Entice (Normani), two aspiring hip-hoppers who are accosted by a menacing racist cop (Mendelsohn) and get their big break when they’re invited to perform in a rap battle versus local legend Too $hort (Symba), whose 1987 song lends the film its title. Given how often it alludes to artists, athletes, and movies and then outright presents them on-screen, it’s no surprise that the real Too $hort makes a fleeting cameo. More stunning is this vignette’s anticlimactic resolution; having paid adequate tribute to the period’s hip-hop, Boden and Fleck simply drop the plot, content to leave this fable as a superficial example of combating sexual denigration through art rather than violence.

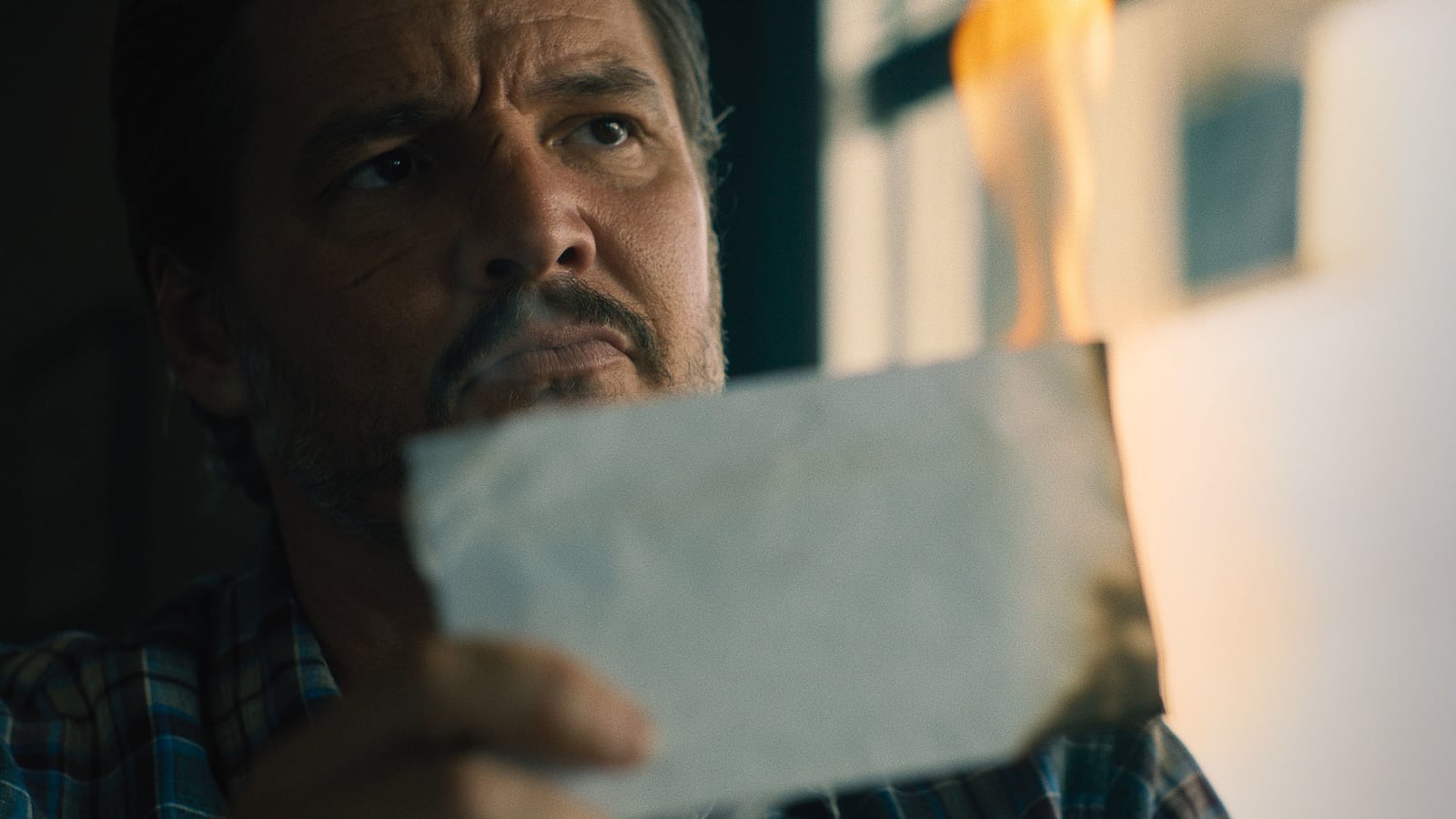

Leering at Barbie and Entice with spiteful sexualized intent, Mendelsohn’s “The Guy” makes for a suitably over-the-top cretin, and the actor’s late theatrics provide the action with a bit of volatile verve. Boden and Fleck, however, aren’t capable of generating genuine gonzo ugliness; they’re more comfortable with self-indulgent shout-outs and wan melodrama. Both of those elements are foregrounded in the film’s nominal centerpiece featuring Pascal as Clint, an enforcer who collects on debts owed to his mysterious boss. Despite being on the verge of retirement and eager to begin a new life with his pregnant wife, Clint sees his happily-ever-after plans die before his eyes after a trip to a video store spirals out of control, thereby forcing him to face the terrible choices he’s made. With a scarred face and weary eyes, Pascal is as affecting as the script will allow, yet the writers/directors never settle on a consistent tone for his story. One second Clint is dryly bantering with a pushy rental clerk (played by an A-lister whose appearance is telegraphed by preceding cine-allusions), and the next, he's grimly reckoning with guilt and fury—competing modes that never satisfactorily mesh.

Also boasting nods to Scanners, Sid and Nancy, Rocky and numerous other genre predecessors, Freaky Tales strives to posit itself as a multifaceted pop culture-infused celebration of little guys (and gals) triumphing over adversity, intolerance and evil. Whether grooving along to Too $hort or banging its head to Metallica, though, it tells as much as it shows, and what it has to show are things that have been seen so many times over the past few decades that it’s difficult to do more than weakly smile and shrug at its mix-and-match rehashing. Even its intertwining-narrative touches are uninspired, and only meaningfully materialize during the conclusion, when they suddenly take on disproportionate importance so things can wrap up in neat-and-tidy fashion. No matter its title, Boden and Fleck’s return to indie moviemaking is short on weirdness, but worse, it lacks coherence, originality, or a point.