Betty Gilpin deleted her Twitter account long ago, but when her book cover was revealed, she dipped her toe into the social media waters to gauge reactions. “There was one comment below, and it was just a GIF of my tits bouncing, like, 'Yeah, that sounds about right.’ I don't know what I was expecting,'” Gilpin dryly recalls.

Drawing a line from decapitated Barbie doll heads on a bubblegum pink background to this GIF is quite the stretch, but this isn’t the first time Gilpin has experienced this kind of gratuitous leap. “I think that when I play a stern lawyer in a turtleneck, sometimes it's metabolized as porn, and the same happens in the literary world,” she laughs.

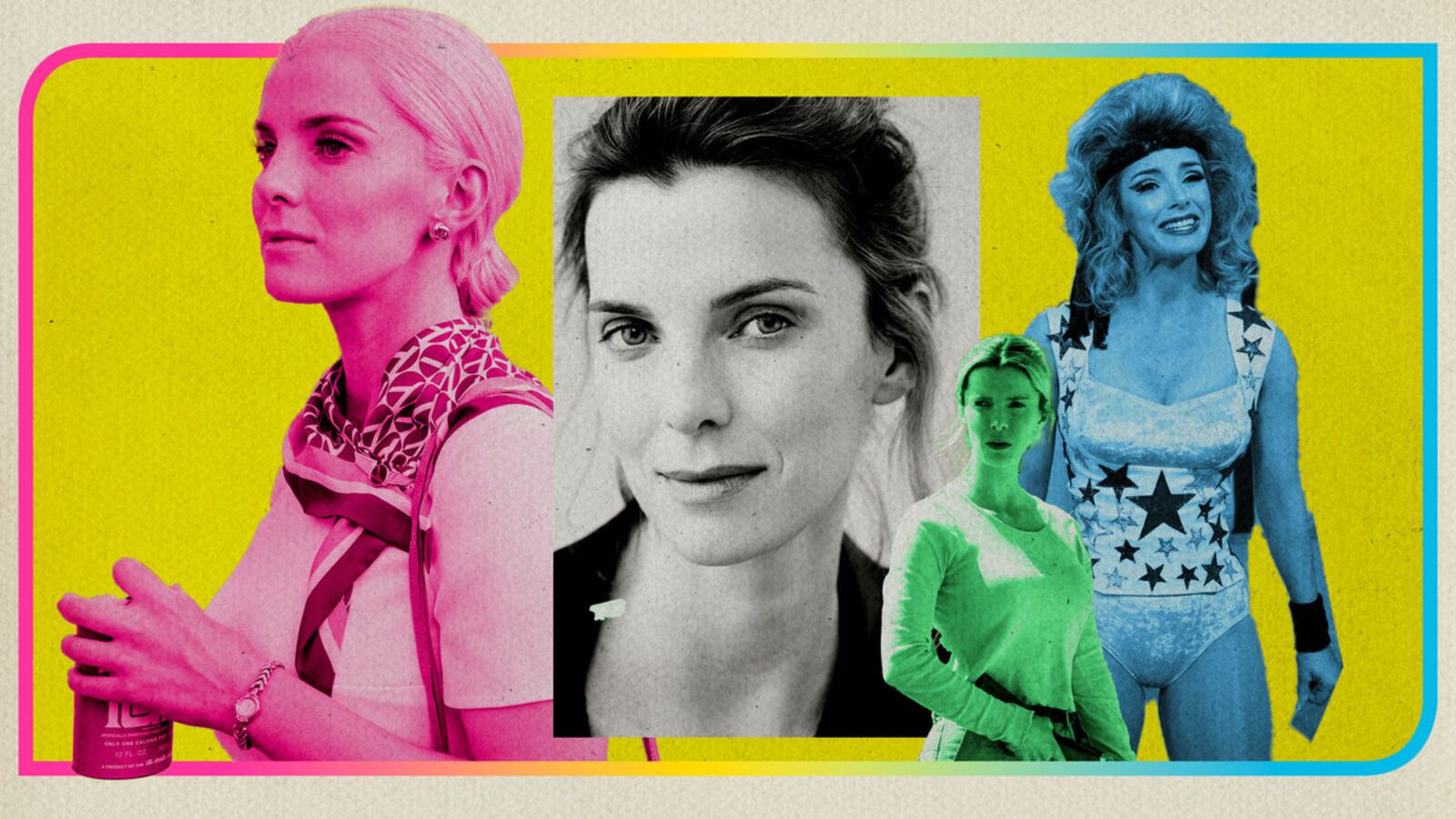

The Emmy-nominated actress has been shooting the forthcoming Damon Lindelof and Tara Hernandez Peacock series, Mrs. Davis in Los Angeles over the summer. A few days in New York City to discuss her essay collection, All the Women in My Brain: And Other Concerns (out now), doubles as a trip home.

Gilpin’s literary talents and ability to wield words like a funny and poignant weapon have been common knowledge among her fans since she first wrote about how GLOW changed her perspective on life in Glamour four years ago. That essay’s honest, hilarious, and whip-smart observations nestled into my mind, where it was joined by Gilpin’s take on acting and the tear-inducing memorial to the canceled-too-soon GLOW (yes, that one still hurts).

Over Zoom, Gilpin is quick with a quip that mirrors her writing style, and I found myself belly laughing as much as I did when reading this collection. Thankfully, you cannot see how smudgy my eyeliner was when the conversation ended.

During the pandemic's early months, many people had plans to dig into long overdue creative endeavors. After all, hadn’t Shakespeare written King Lear while in quarantine? But Wills also didn’t have the entire Columbo DVD box set to watch (my lockdown project).

Gilpin went with the first option as she had “no excuses anymore not to sit down and do this thing,” she says. More importantly, she no longer hated the sound of her voice. In the past, it would have been “brand betrayal if I were to put my voice on paper and try to sell that piece of paper.” Luckily for us, Gilpin has aged out of this feeling and jokes, "I'm completely selling out and selling my self-loathing.”

March 2020 saw the release of Gilpin’s headline-stoking political satire movie The Hunt (which she does discuss in the book); it was also around this time that she found out she was pregnant. She wrote some of the essays, like “Salem or Barbie” (a metaphor used to reflect authentic and presented self), before she gave birth.

In “Girl Baby,” Gilpin discusses her fear about having a girl, which she wrote during her pregnancy. The couple didn’t want to find out the sex of the baby ahead of time, but Gilpin was convinced she was having a boy. “I think having Mary and the hormones that came after it, ‘Oh, now is the time I think I have it all in my head.’ I wrote the bulk of it when she was like five weeks old,” she says, which is quite the reverse of writer’s block.

“In giving birth to a girl, it crystallized—for me—the themes I had been thinking about,” Gilpin says. “Authentic self versus presented self, being a blanket feminist but eye-rolling to the woman who's standing next to you, and projecting your demons onto other women… Being an actress is an allegory for being a woman in the world of cycling through selves to find the best version of yourself when, of course, it's the in-between versions that are you.”

Gilpin doesn’t always name the TV or movie projects by name in her essays (“I was self-conscious about [that]. I didn't want the reader to think that they needed to know who I was to relate to the book”), but GLOW is not on this list. I won’t spoil the story Gilpin tells about what happened at the start of production, but suffice to say, a lot is going on at this point in her career.

What is clear is how pivotal playing Debbie Eagan (aka Liberty Belle) is, both professionally and personally. “I think working with a big group of women honestly made me hold myself accountable for the ways in which I was standing in my own way and judging other women,” she says.

Gilpin’s evocative use of metaphor isn’t restricted to her writing, as her description of this lightbulb moment proves: “Being honest about the ways in which the shame calls were still coming from inside the brain house. I had this narrative in my head that, 'Oh, I'm a craggy, sea-captain character actress, and it's the world that's putting this Barbie thing on me, but I have to pay this toll of being Marilyn-y and wearing the tight costume to shoehorn in the gargoyle-y stuff.’ I think I realized, ‘Oh, none of these other women are doing that.’”

Part of this goes back to the book cover anecdote. In the past, she was “afraid to take the risk of presenting my soul or brain alone as a thing by itself.” Cleavage was a surefire hit for some demos uninterested in the soul part. “There's always going to be a part of the world that's 'really not interested in your soul, but love the cleavage,' hence the GIF of my tits under my book cover announcement,” she says.

However, this essay collection is taking a new approach: “The book was a real exercise for me in seeing what happens when I put forth my thoughts without cleavage.”

All the Women in my Brain grapples with the contradictions of being an actress and a woman in this industry (and the world). Not every character has nuance and multitudes, and she vividly recalls the less glowing jobs (no pun intended). One story involves the phrase “raw flesh epaulets.” (Again, I don’t want to spoil it.) It is also here that I should mention the audiobook, which Gilpin narrates with as much range as her best work. (A word of advice; don’t try to apply makeup while listening to the last essay, a mistake I made).

Her love of evocative imagery is baked in at birth as Gilpin’s parents are both actors primarily on stage in New York—in addition to the requisite Law & Order appearances. Her face lights up when I tell her that whenever she mentioned her father, Jack Gilpin, I couldn’t help but picture him in his current butler role in The Gilded Age. She wrote the book before he was cast as Church but explains it is a part he is born to play, “His soul has probably always been a 71-year-old butler since he was three years old, and now he's playing a 71-year-old butler; it feels like something in the world has perfectly clicked into place in the way that it should.”

While she notes that neither her mom nor dad speak in metaphor, there was a lot of “fantasy, selfishness, and imagination” in the Gilpin home. “I think growing up in a house where every opportunity it was Maria von Trapp making clothes out of the curtains, but with fart jokes, pratfalls, and gravitas—which is what The Sound of Music should have been—completely bled into the way that I live and write.”

Given how many hours she spent in the wings of a theater growing up, it isn’t a leap that Gilpin followed in her parent's footsteps. Rather than taking center stage, Gilpin discusses how she cast herself in the supporting role. “Maybe we all commodify our strengths and demons. I realized that I’ve commercialized the feeling of being a sidekick in other people's stories,” she says. “That's how I felt on the playground, and now what I do for a living.”

As with most topics, Gilpin crisscrosses between personal and professional reflections. Writing a book that peels back the layers is a reflective process; motherhood has given her a different perspective on the stories being told. “I feel like one throughline is your brain offers you the option of, ‘What if you saved time in the day by just erasing yourself and your own needs?’ You realize how easy that could be.” She adds, “I think it's from a lifetime of telling yourself that your job is to be the B story in someone else's biopic.”

Again, it is the contradiction of being a woman in 2022. “We’re in this weird time where we're celebrating the march of a feminist victory before having the victory itself,” she says. “We're trying to step into our own A story while still being weighed down by tropes and contour, and it feels so silly and insane. But we're doing it, I guess.”

This applies to the roles Gilpin has gravitated toward since GLOW’s abrupt cancellation. In Gaslit, Gilpin shined as Mo Dean alongside a captivating and Emmy-snubbed Julia Roberts (“Something is emanating from her that is otherworldly and very exciting. I tried to be cool and wasn't cool at all,” she says about meeting Roberts). Gilpin cites this role as an “example of where my lines used to be as the blonde wife, ‘How was work? That sounds confusing.’ Now my lines are, ‘How was work? That sounds dumb. Here's what you should do.’ But I have the same amount of lines,” she notes with a wry laugh. “The guys still have the biggest part. But we're getting there slowly. Little by little.”

One show that eschews this masculine status quo is the forthcoming Showtime adaptation of Lisa Taddeo’s best-seller Three Women. Gilpin read the searing debut when it came out in 2019 and was determined to be cast. Why was she obsessed with booking the role of Lina? “Maybe because I have a low voice and rescue-dog-damage behind my eyes, and curves, a lot of the parts I play are a woman with her arms crossed with all the answers—like a Magic 8 Ball with tits,” she says. Lina in Three Women is anything but a “Magic 8 Ball with tits.”

“I really wanted to play somebody whose needs and wants were so boldly and embarrassingly puked up on her dress in front of you—instead of being cool and eyeliner-y.” she passionately describes. “Lina was such a raw, pulsing need of a character and the kind of person you immediately recognize that she can't help but be this open chasm.”

Three Women tells intimate stories about desire from three “ordinary” women who have reached a crossroads, which are based on real experiences, and is unlike anything currently airing in a crowded TV landscape. “Lisa Taddeo beautifully writes about all the in-between moments that we're not supposed to see or talk about,” Gilpin describes. “I think we're trying to go back and tell these stories about those moments.”

It almost wasn’t to be: “I chased the part as hard as I could. They cast somebody else. I was devastated. That person dropped out. I made a Hail Mary audition tape.” Gilpin had a Zoom conversation with Taddeo, but because she didn’t know when production was, she hid her pregnancy. Gilpin moves the screen to show the top of the head visual Taddeo saw (aka the angle whenever I FaceTime my mother). Thankfully, it all worked out, and the fruits of that labor will be coming to Showtime this fall.

After a few days promoting All the Women in my Brain, it will be back to Los Angeles to shoot Mrs. Davis—or what Gilpin affectionately refers to as “the nun show.” Details are light other than Gilpin in the lead as a nun battling an all-powerful A.I. “It's been a lot of sprinting and sobbing in a habit over the summer,” she can vaguely offer. As if I needed any further incentive beyond that description, Margo Martindale will also be sporting Catholic garb. Gilpin is equally enthusiastic about her costar, “All my dreams came true when she walked on set in a mother superior outfit. Like my entire life has been leading towards this moment.”

The day after we talked, I emailed a follow-up question about Mrs. Davis and whether this show reflects her hopes for the kind of work she wants to do in the future, and how it sits in the Salem/Barbie of it all. Gilpin’s answer encapsulates the relatable contradictions rippling through her writing:

“It is definitely bubbling with Salem-dom role wise. What's saddest is I will probably age out of the Barbie stuff before I mature out of relying on it myself. I’ll be insisting I’m a suffragette while taping my neck until they wheel me into the sea. I try to make fun of myself and call my own bullshit, but I by no means have it figured out. My impending crows feet will force an internal empowerment revolution before my journal does, and my daughter will probably roast me for that.”

Nuns, wrestlers, the blonde wife—here’s to all the women in Gilpin’s brain and on-screen.