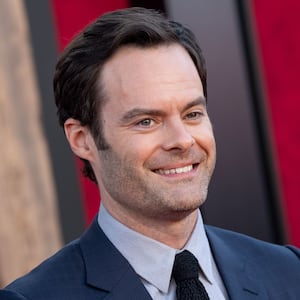

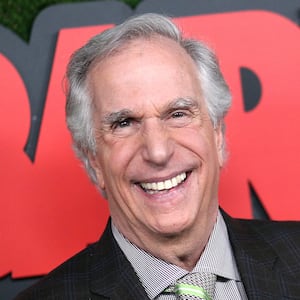

Henry Winkler has doubted himself throughout his long and storied career. From landing the coveted role of Arthur Fonzarelli on Happy Days to winning his first Emmy Award for playing Gene Cousineau on Bill Hader’s Barry, the beloved actor has struggled to overcome what only became known as “imposter syndrome” in recent years.

“I invented the syndrome!” Winkler says in this week’s episode of The Last Laugh podcast. On the heels of his third consecutive Emmy nomination for Barry, we break down the HBO series’ “intense” Season 3 finale (consider this your spoiler warning). Winkler also tells stories about his struggles to find work after being The Fonz, explains how Adam Sandler helped revive his comedy career, reveals why he turned down hosting SNL, recalls his funniest line from Arrested Development, and so much more.

When Winkler appears in the Zoom window for our interview, he has just returned from one of his treasured summer fly-fishing trips. A few years back, he published a book of anecdotes and photos from those idyllic adventures called I’ve Never Met an Idiot on the River. It’s true, he tells me: “Basically, people who fly fish are pretty wonderful.”

Now, those images of Winkler holding up his latest catch go directly to his nearly 1 million Twitter followers, who celebrate them as perhaps the only positive content on that godforsaken platform. For a long time, the 76-year-old actor says he was “baffled” by the joy his photos brought to the masses. But now it is “so scary out there,” he says, “that the joy of nature and the fish and my true exuberance” might just explain it.

As we speak, he’s just a few days away from the start of production on Barry’s fourth season. But he is sworn to secrecy about what’s in the scripts he’s been given so far. “HBO has acquired a guy named Gino who stands in the corner, who’s very large,” he jokes. “And if I say anything about what I’ve read, Gino reminds me to shut up.”

At the beginning of every season, Winkler asks Hader, “Hey, Bill, am I dead?” And “thank god,” the answer so far has been no.

But whatever happens to Gene in Season 4, Winkler has no plans to retire when his time on the show is up, telling me he is keeping his mind open to whatever comes his way next.

“When Happy Days was over, I had an office at Paramount with a big red leather chair,” he explains. “And I sat in my leather chair and I put my feet up and my brain hurt. ‘Will I ever do anything as meaningful? Will I ever do anything with as much impact? What will it be? How will I know?’ I was inert. I was in a panic of inaction. And from then till now, I have learned, you never know.”

Below is an edited excerpt from our conversation. You can listen to the whole thing by subscribing to The Last Laugh on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Google, Stitcher, Amazon Music, or wherever you get your podcasts, and be the first to hear new episodes when they are released every Tuesday. Warning: ‘Barry’ spoilers ahead.

You’ve said that you always felt like you were very different from The Fonz in your own personality. How similar do you feel now to Gene Cousineau?

That’s a good question. Because what I failed to say at that time is that every character that you ever play is inside you. Every good character that is ever written is already there. We’re all the same. And then you have to delineate personality traits, but you start with yourself. So Gene started off as an asshole and as I played him, without thinking about it, there were rays of warmth. So he is close to me. I hope I’m not as much of an asshole as he is.

In this third season, we really started to learn how big of an asshole he was in his early days. And these stories start to come out of all these horrible things that he’s done to other actors and people he’s worked with. Of course, you are well known as one of the nicest guys in Hollywood. But do you ever worry about people telling stories about you that make you sound less nice than you are perceived to be?

You know what? I’m not nice, I think, as much as I am grateful. And I am grateful that I’m walking on the Earth. I’m grateful that I had a dream and I’m still living it. I’m grateful for the group of people that I am working with. So I used to care a lot more—I can honestly say I used to care a lot if I thought someone was talking about something that was not the image I wanted to be. I now know that I’m frail and human.

So if someone did tell a story about you that didn’t align with that image—

As long as it was true, that’s the way it is.

Now that the season’s over, we can talk about that big twist at the end where Gene basically helps trick Barry into getting arrested. What do you think is going through Gene’s mind in that moment, when he was watching this guy taken away in handcuffs?

At that last moment, I’m looking at the guy who killed Janice, who killed my future, my emotional future. But before that, I think I’m very ambivalent. I mean, one of my favorite scenes ever was the one with Robert Wisdom in his garage. In that scene, I am standing on the shoulders of Robert Wisdom.

Did you know when you read that scene how intense it would be to act?

No. We shot it, I think, five times in a row. I wasn’t even sure that I would be able to fully fill that five times in a row. And I’m telling you, there is an acting god who is looking down on me.

You’ve said that the scene in the garage was the most intense work that you’ve done since Yale Drama School.

True.

What did you think that your career would be back in those days when you were getting that training?

When I was training, when I was 22, 23, I was like a muffin when you’re baking it and you take a toothpick and you put it in and the center is not done yet so you put it back. I went back into the oven for the next 40 years. I’m a late bloomer. Whatever my learning challenges, whatever my background is, my real emotional self never was able to flower until later in life.

So do you think that that held you back in the early days when you were trying to get work?

Without a doubt. What really held me back, except that I wouldn’t have changed a hair on its head, when I changed my voice, The Fonz came out like a torrent. And because he was so popular, you don’t beat typecasting, you don’t beat the system.

It’s like the epitome of a blessing and a curse, that character, right?

More blessing, I have to say. I would not give that back for my entire life. It was just amazing, what happened in my life because I played The Fonz.

And it wasn’t that long after you got out of drama school that you got that role?

I got out of school, went to New York for a year and a half, did The Lords of Flatbush, did a lot of commercials, came out here [to L.A.] for one month, and in the second week I got The Fonz.

What was the process like of getting that role? It was something I know a lot of actors were going in for at the time, right?

The process is, one of my teachers, Bobby Lewis, rest his soul, one of the great acting teachers of history, he said to us, “Your job is to get the job.” Once you get the job, your job is then to do it. But you don’t worry about anything else except getting it. And I was ferocious in being single-minded about getting the job. The other thing is changing my voice. Changing my voice changed my life. As soon as I changed my voice, I was unleashed.

They could see it, obviously, that you could do this role, even though he wasn’t you.

Garry Marshall saw it. He wanted a big, six-foot Italian. They got a five-foot, six-and-a-half-inch Jew.

So you got famous very fast after that when that show took off. How did you handle that emotionally, the fame aspect of it?

I never believed what other people were saying. I liked that they were saying it. It was pragmatic that they were saying it, because I was reaping the benefit, but I never believed that they liked me that much, that I was that successful. It was like two different worlds.

I saw somewhere that you actually turned down hosting Saturday Night Live at some point. Was that during that time?

Exactly. I was not ready to do that job. I could not do that job the way that it’s supposed to be done.

Did you have any regrets about that afterwards, turning it down?

No, but I am ready now. I could do it now, but I couldn’t do it then. If it came, I would be scared. I would be nervous, but I could climb that mountain. Then, I was in the foothills and I set up camp there and I wasn’t moving.

Was it a lot about the fear of reading the cue cards or was it selling more than that?

No, it was my being awkward. If I couldn’t be that character, I didn’t have a lot to offer.

What you’re describing is often called imposter syndrome, where you don’t believe you can do something or don’t think you should be there. It sounds like that’s something that you’ve dealt with a lot.

Oh my, can I just say, I invented the syndrome!

Do you get over it, or is it always there with each project that you do?

You get over it. As I did work on myself, as I opened and I was able to mature, the imposter syndrome takes a backseat. Now, it’s still there. It’s a habit, maybe. It starts to invade and you’re able to beat it back into submission and just do what you know you’re supposed to do.