Leeloo’s (Milla Jovovich) epic dive into a sea of traffic is the iconic moment of The Fifth Element that lingers in every one’s mind after their first viewing. Twenty-five years on from the film’s cinematic release, the Gaultier bandage look has since been recreated countless times, with homages even appearing on RuPaul’s Drag Race: All Stars. Jean Paul Gaultier’s colorful constructions add to the bright world that Besson creates, one of extremes the luxurious and the impoverished, the grandiose and the desperate.

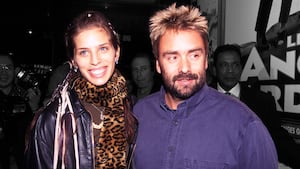

The fashion of Fifth Element is so iconic that, much like our societal celebrity obsession, it often distracts the viewer from the grim reality of Earth that director Luc Besson created. Whether you love or loathed the looks of the Met Gala, the glitzy celeb-filled red carpet event still—depressingly—garnered as much, maybe even more, commentary online than the news that Roe v. Wade may be overturned.

In a sad twist of fate, Besson’s art is too close to its imitation of life, something that revisiting the film on its 25th anniversary makes hauntingly clear.

When we think of The Fifth Element, the first images that come to mind are Jovovich’s orange hair and matching suspenders or Chris Tucker in a tight leopard print number—even the golden arch uniform of MacDonald's servers appears before the polluted depiction of earth. More discourse has surfaced in the past years discussing the epic fashions of The Fifth Element than have discussed its depiction of the climate crisis. Besson’s dystopic masterpiece has, in a way, become victim to its own success.

Leeloo’s dive into the city is not only stunning because of the gymnastic beauty of a scantily wrapped model body flying through the sky. The scene is held in our minds by the composition between her supple natural skin, and the unnatural cacophony of this polluted world. She plummets into layers of traffic, an extreme version of our reality. It’s levels and levels of hover cars in a traffic build up that is stories high. Clearly the invention of the hover car did not prevent traffic, it only allowed humanity to fill the skies with more vehicles and more roads.

It is the great joke of capitalism’s technological advantages, that every advancement only succeeds in making more clutter on the earth’s surface.

When we think of a dystopian future world, one which is corrupted and collapsing, we think that we should see blocks of gray, mounds of rubble, and desolate lands. But what Besson creates is a world just on the cusp of causing its own destruction. There are little signs dotted throughout Besson’s vision, from the polluted sky line visible from Zorg’s penthouse to the luminous fuel that the cruise ship emits, so toxic that it kills animals on impact.

The Fifth Element is a prediction of the global capitalist nightmare we find ourselves in. Besson saw from the viewpoint of the ’90s where this society was headed. A reality that was beginning when The Fifth Element was first released has snowballed into hyperbole, where consumerism and celebrities distract us from the awful truth. Humanity is careening towards extinction while critiquing beautiful gowns and aspiring to become the millionaires that exploit our daily lives.

The luxury cruise liner that Leeloo and Korben (Bruce Willis) must infiltrate to save the world reminds of the Met Gala. It is a spectacle of extreme wealth that we all watch and wish we could have one small crumb of. We are not dissimilar from Korben’s mum, annoyed that he’s not inviting her on the luxury cruise ship as his plus one. She shouts down the phone at her son, reminding him that she deserves a holiday!! We all want the gluttonous shows of luxury to end, but not before we get our chance at being pampered first.

Ruby Rohd (Chris Tucker), the himbo presenter, hosts a radio show that offers the public a glimpse into the elite. But instead of showing his audience what rich people get up to, he is thrown into a battle. His reporting becomes a close up of war rather than a boast of wealth. One can almost imagine Emma Chamberlain crawling through the Met as war wages offering her shocked commentary through a head piece.

Leeloo, who is technically only days old and born with the knowledge that it is her duty to save the world, must learn everything about Earth. She rapidly reads everything on the internet, using it as an encyclopedia of world history. When she reaches the letter ‘W’ she finds out about war. The viewer watches images of destruction, bodies, and atomic bombs flicker across the screen and her eyes fill with tears.

We have become so numb to the realities of our world that being inundated with all those facts and images all at once at that moment in the film is as overwhelming for us as it is for Leeloo. We are so used to carrying on with our daily lives, like the commuters in Besson’s spaceport who walk past the wall of garbage unperturbed, that it takes a lot to break through to us. It is learning the violent actions that humanity is capable of which almost prevents Leeloo from completing her mission. She is thrust into an existential crisis. It is our nihilistic hero Korben that ends up convincing her that there is hope for humanity.

Although Korben Dallas and Jean Baptiste Emmanuel Zorg (Gary Oldman) are pitted against each other, a reluctant war-vet hero and an arms-dealing villain, there are parts of both of them in all of us.

Korben’s nihilistic view on the world and resignation to a post-apocalyptic fate is scarily relatable, especially as a post-pandemic climate catastrophe is our new reality. The darkest truth is that, while Korben can save the world and get the girl in this sci-fi action film, this is not a possibility for us. That’s why we resort to Zorg’s consumerist delusions. It’s easier to buy gadgets to deflect from our growing isolation and convince ourselves that bringing about the end of the world won’t also mean the end of us.

Luc Besson’s sci-fi camp classic almost too accurately predicted the hellscape in which we find ourselves in today. His love for plastic shiny worldbuilding with constant nods to a civilization literally littered with gadgets and convenience shows a human race headed for disaster due to its own technological success.

But just like the gadgets we distract ourselves with, his brightly coloured universal and its iconic fashion succeeds at pulling focus. The Fifth Element’s warning that humanity must return to the elements before it’s too late is easily forgotten. As in life, compassion for the world we are on the brink of losing is lost amongst a haze of consumerist treasures.