This is a preview of our pop culture newsletter The Daily Beast’s Obsessed, written by editor Kevin Fallon. To receive the full newsletter in your inbox each week, sign up for it here.

The worst part of I Wanna Dance Somebody is how it makes you feel as it approaches its interminable end. “Please,” you think. “Will Whitney Houston just stop singing?”

It’s an egregious sin to make your audience tire of hearing Houston’s voice, but that’s just what the new biopic, now in theaters, does. At a running time of nearly two-and-a-half hours, I Wanna Dance With Somebody endeavors to be an all-encompassing document of Houston’s entire career: Her discovery by Clive Davis. Her meteoric rise. Her unparalleled success. Her drug use. Her relationships with Robyn Crawford and Bobby Brown. Her comeback, and her death. It’s a Wikipedia article as a film, and at some point, you just want to stop scrolling.

That’s a shame, because there is a lot to admire.

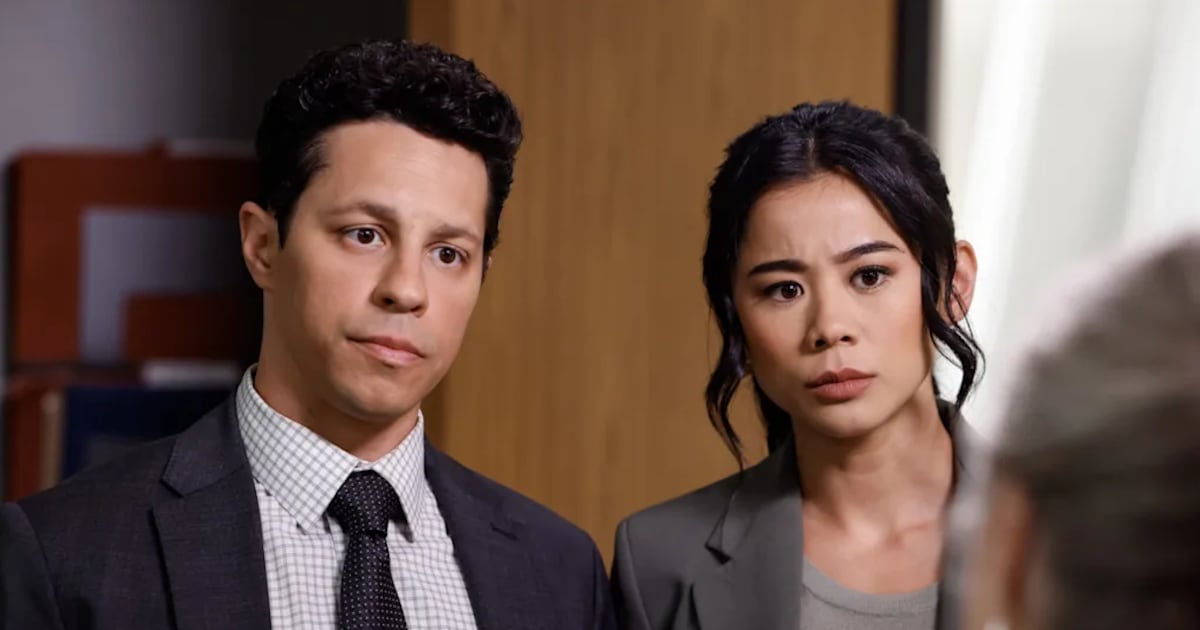

Naomi Ackie, who plays Houston, is incredible. I can’t remember the last time I saw someone so luminous on the screen. She nails Houston’s speaking voice and her mannerisms, and calibrates them through each stage of the performer’s life. You never feel like Ackie is playing older or younger than her age; she simply inhabits Houston at every moment. Especially during scenes that should feel like they were written for a Lifetime movie (of which there already has been a terrible one about Houston), Ackie taps into a vibrancy and emotional immediacy that not only stops you from cringing, but also overwhelms you with excellence.

But watching I Wanna Dance With Somebody is, overall, a strange experience. It is a crowd pleaser. It features all of Houston’s most iconic performances. At my screening, people applauded after each song, as if they were watching Houston herself sing. (Ackie lip syncs, impressively, to recordings of Houston’s voice.)

The movie borders on being a concert film, which is fan service that it’s too preoccupied by. There is so much insistence on meticulously portraying every memorable note, movement, and glance, leaving the scenes that are supposed to reveal what it took for Houston to produce them to seem like an afterthought.

Yes, it’s a thrill to watch the film’s depictions of Houston singing “Home” in her debut on Merv Griffin’s talk show, her a capella opening to “I Will Always Love You” while shooting the music video, and her comeback performance on The Oprah Winfrey Show. I got chills and teared up at the frame-by-frame mimicry of her famously singing the National Anthem at the Super Bowl. I also have watched all of those performances—many times—on YouTube, with Houston actually doing the singing.

Because we’re in the digital age, and historical clips of major pop-culture moments are readily available, movies and TV shows are now regularly recreating them exactly. It’s as if studios are already planning for the inevitable side-by-side comparison that will go viral on Twitter or TikTok. But that becomes unbearably robotic. By the third or fourth (or sixteenth) time I Wanna Dance With Somebody does that with Houston’s performances, it’s exhausting.

The performances run so long and are so exact in the copying of Houston’s mannerisms that, especially knowing that you’re not hearing Ackie sing live, the experience verges on watching drag. That is, in a way, high praise—it’s an artform, and one that I love. But at some point the uncanniness becomes bizarre. It becomes clear that someone paid a lot of money and spent a lot of time to remake the videos you can already watch on YouTube.

More surprising is the film’s exploration of Houston’s private life. I have to say that I didn’t expect the movie to dive as deep as it did into Houston’s relationship with Crawford, from friend to lover to manager and back again. The last third of the film also attempts to offer what you crave for the whole running time, providing the humanity behind the gossip in its depiction of her drug use. These scenes are a tremendous showcase for Ackie, and are also the film’s greatest justification for existing in the first place.

Music biopics are meant to provide this level of insight into an artist. We want to learn something about a celebrity we revered, to understand her as a person. Instead, I Wanna Dance With Somebody is relentlessly committed to its recreations of Houston performing. The music is obviously important, and it’s a thrill every time the opening notes to one of Houston’s hits begin and you know you’re about to watch a performance. You want to cheer at the end of that Super Bowl moment, and the film lets you do that. But it should not stand in the way of creating character depth—yet often does.

I’m harping on that because the movie does. It is so long, and so much of the running time is devoted to those musical numbers. When the scene happens where Houston performs “I Will Always Love You” for the first time, I thought the movie was ending and that it was just charting that part of her career. It turned out that there was still nearly 20 years and more than an hour that the film planned to cover.

There’s something cynical about this bullet-points approach to Houston’s life and career that comes into focus when you learn that the writer, Anthony McCarten, also scripted Bohemian Rhapsody, the biopic of Freddie Mercury. That film was a huge hit, and Rami Malek won an Oscar for so believably lip synching to Queen’s songs.

Critics of the movie, myself chief among them, blasted its exploitation of the darkness in Mercury’s life for plot-point scandal, rather than attempting any sort of real, human exploration. That reductiveness, of course, helped Bohemian Rhapsody stick to a by-the-numbers structure that would have anyone clapping at the end. But that film’s portrait of an incredible artist was ultimately superficial. I Wanna Dance With Somebody suffers in the same way. The film feels like the cinematic manifestation of a producer saying “let’s do the Bohemian Rhapsody thing, but with Whitney.”

After I Wanna Dance With Somebody shows Houston’s death, it then recreates Houston’s jaw-dropping medley at the 1994 American Music Awards in its entirety. For 10 minutes, Ackie replicates every jaw movement and gesture that Houston made while performing songs from Porgy and Bess, Dreamgirls, and The Bodyguard. It’s considered Houston’s greatest live performance, a point that the film teases several times before we finally see it at the end.

You want to celebrate Houston’s brilliance, so you go along with it, even though it’s a lip synched version of something you can actually watch her do right now. But then the movie exposes that illusion. As the credits roll, it starts playing the actual footage of Houston herself on that night. It left me with the biggest “So what was the point?” realization I’ve ever had while watching the movie. What was shocking was that I Wanna Dance With Somebody never bothered to even contemplate that question itself.

Keep obsessing! Sign up for the Daily Beast’s Obsessed newsletter and follow us on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and TikTok.