In its sprint toward the finish line, Better Call Saul has been the following things: shocking; thrilling; nostalgic. After last night’s episode—the series’ penultimate—we can add one more to the list: utterly heartbreaking.

(Warning: Spoilers ahead for the most recent episodes of Better Call Saul.)

I don’t mean to suggest that this season hasn’t been heartbreaking thus far. Three episodes back, the show devastated us with Jimmy McGill (a.k.a. Saul Goodman a.k.a. Gene Takovic a.k.a. Bob Odenkirk) and Kim Wexler’s (Rhea Seehorn) breakup. It was an unsurprising moment, because we knew Kim was going to skip town before the events of Breaking Bad, but to watch her leave the love of her life behind hurt all the same.

But the tears I shed then are nothing compared to the tears I shed during Episode 12, “Waterworks”—aptly named. Better Call Saul twisted the knife in its second-to-last hour by breaking our beloved Kim all the way down for the first, and probably last, time.

Over the course of six seasons, we’ve never seen Kim truly let go. In the courtroom, she was the pinnacle of steadfast; with Jimmy, she was caring but not exactly warm. She maintained her composure just enough to end things with Jimmy, turning her back to him before he could see her shed a single tear. When a drug lord ordered Kim to shoot someone on his behalf, she pleaded with him to let her go—but then she sucked it up and (almost) did it. She held a straight face when lying to Howard Hamlin’s (Patrick Fabian) wife about Jimmy’s and her role in his murder. Kim wears her ponytail back so tightly, it’s almost physically painful to look at.

It should go without saying, then, that Kim Wexler is not a woman who cries. Until now.

Since leaving Jimmy, Kim has started a new life in Florida: She has a lame-o boyfriend, who freaks out about buying Miracle Whip instead of mayo and grunts, “Yep…” during sex. She works an office job for an irrigation company. And she lets her hair down—once sleekly blonde, it’s now a dark, dull brown.

It’s hard to see Kim, an excellent lawyer with a rigid moral compass, whose dream was to offer the best-possible pro bono service to clients in need, living like this. But it’s also a relief that she’s free from Jimmy’s line-skirting ways; she avoided getting sucked into his downward spiral into a life of inexcusable crimes, grifts, and garishly colored suits.

She’s managed to avoid revisiting her past, even as Jimmy made national news for his part in the whole Walter White thing. But Jimmy finally gets through to her on her office phone, checking in with her after six years of silence.

It’s a hard conversation to see unfurl. “I’m still getting away with it!” Jimmy tells her with a sense of unearned, un-self-aware pride. We watch as Kim anxiously tries to stay measured. After Jimmy boasts, she says, “You should turn yourself in,” for the crimes that he’s done—including the ones she was involved with, the ones that got Howard killed. “I don’t know what kind of life you’ve been living, but it can’t be much.”

She’s right: As Gene Takovic, Jimmy’s been living in Nebraska selling cinnamon buns and helping dumb-dumbs commit petty crimes. But Jimmy’s response is immediate, cruel, and finger-pointing. “That is really rich—you, preaching to me? … Why don’t you turn yourself in, seeing as you’re the one with the guilty conscience?” She’s a pot calling the kettle back, Jimmy says. “Spill your guts, put on your hair shirt, see where that gets you!” (He’s always been great with the snappy snark.)

Kim is, indeed, the one with the guilty conscience. It’s what’s always made her the better person—probably the closest member of the Breaking Bad universe to being an objectively good human.

So she flies back to Albuquerque and files an affidavit naming herself and Jimmy as complicit in the murder of Howard Hamlin. She hands it directly to Howard’s wife (Sandrine Holt), who cries, yells, and coolly asks Kim why she’s doing this. Kim can’t answer the question; she can’t begin to articulate how afraid she is. She also isn’t sure what all of this will amount to—because, even though Jimmy is alive and could certainly use this to ruin her life once again, the likelihood that he’d ever admit his guilt is slim.

Then comes what is hands-down the most tear-jerking scene Better Call Saul has ever aired. I will never forget this: Kim gets on the shuttle bus back to the airport. As she sits, the camera holds on her, clutching her bag to her chest. It’s clear that Kim’s reckoning with the weight of what she just did. She’s reckoning with the weight of what she did six years ago. She’s reckoning with the weight of what she’s done every single day since then.

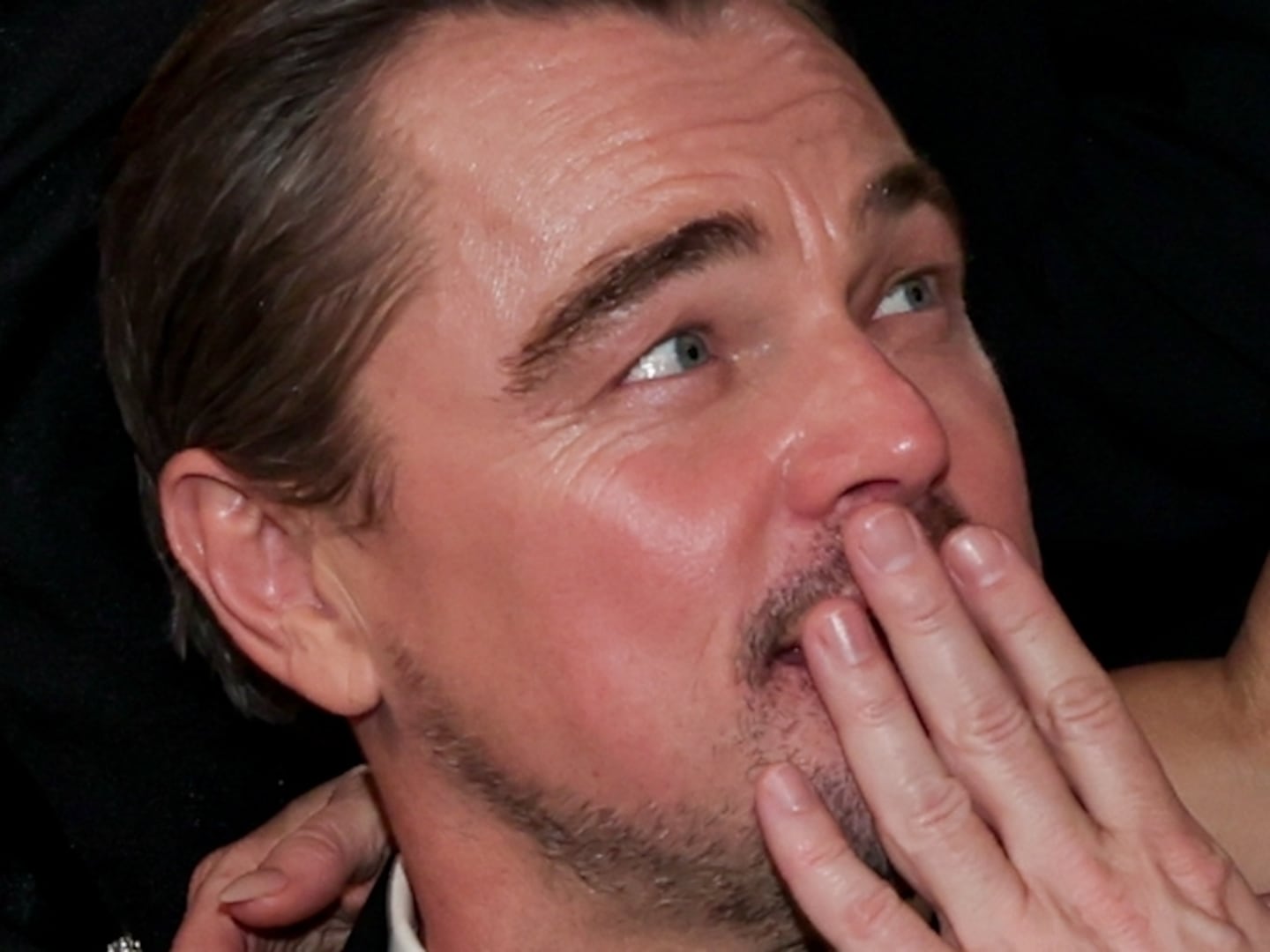

Finally, it’s too much. What she does is so familiar to me, as a public crier. Kim at first bites her lip, scrunches her face, shakes her head to push the tears back in. The first sob comes out almost like a sneeze, abruptly and unstoppable. Kim quickly covers her mouth to muffle the sound and force her sadness back inside of herself—deep down, in the pit of her stomach, where she’s let it fester for all this time.

But she can’t do that anymore. Kim Wexler proceeds to weep.

If anyone ever deserved a good cry, it’s Kim. And so I, too, cried. To watch such a strong woman finally access all that pain and trauma and hurt and let it subsume her is a difficult thing. But it’s also a liberating moment; there’s a freedom that comes with throwing off the shackles of your guilt, allowing yourself to feel your feelings.

Watching Kim feel her feelings made me immediately crawl inside of myself and find my own. If it doesn’t inspire that same painful empathy in you, I wish you the best—because, just like Jimmy McGill, there may be no hope for you. This is heart-shattering TV at its absolute, perfectly executed best.

For more, listen to Rhea Seehorn on The Last Laugh podcast.