In the Land of Saints and Sinners opens on a busy pub, but its introductory text spells trouble: “Northern Ireland, 1974.” A bombing attempt goes awry, sending its IRA perpetrators—led by the ruthless liberationist Doireann McCann (Kerry Condon)—on the run from Belfast to a coastal town in Donegal, just south of the border. They decide to lay low, but this quaint village in the Republic of Ireland happens to be the home of hitman Finbar Murphy (Liam Neeson), whose path they eventually cross, resulting in a consistently watchable (if politically disengaged) drama about regret.

The film is an Irish production, but American filmmaker Robert Lorenz imbues it with a distinctly Western vibe. The opening notes of its score by siblings Diego, Nora, and Lionel Baldenweg sound distinctly inspired by Ennio Morricone, albeit with the occasional use of Irish folk instruments. These settings may not mix on the surface, but Lorenz’s Wild West approach to Troubles Ireland is less about flash and more about introspective mood.

It also feels inspired by Lorenz’s longtime collaborator, Clint Eastwood. Despite its use of echoing, Morricone-esque flutes and harmonicas in its score—reminiscent of Sergio Leone’s The Good, the Bad, and The Ugly, which starred Eastwood—the movie takes more after Unforgiven, a deconstructive neo-Western. Like Paul Munny, Eastwood’s character in that movie, Neeson’s Finbar is a widowered former assassin. Unlike Munny, his bounty-hunting days aren’t quite so far in his rearview.

In an amusing coincidence, Finbar—who moonlights as a book salesman—happens to retire from his life of crime the very same day that Doireann and her crew arrive. With Neeson in the role, it’s a pleasure to see his cold-hearted determination slip and transform into remorse in real time. His raspy delivery of “I have a very particular set of skills” in Taken is iconic, but the way he stews and reflects in silence is infinitely more powerful. (See also: Joe Carnahan’s survivalist thriller The Grey.) Lorenz knows exactly how to deploy Neeson’s gifts; his dialogue, especially his chummy bickering with cop friend Vinnie (Ciarán Hinds), is a pleasant front to conceal lurid secrets.

For all the moral murkiness of its backdrop, In the Land of Saints and Sinners is surprisingly straightforward in that department. Finbar’s life as a button man may weigh heavy on his heart, but he rarely actually reckons with his actions. The film practically establishes up front that killing people who have it coming, in some fashion, is a-okay. Finbar is a murderer with a heart of gold, who shows kindness to a neighborhood girl just trying to bring groceries home to her family. So when he discovers that one of the IRA bombers has been hurting the young lass, well, the solution isn’t complicated.

A cat and mouse game ensues, as Finbar plays mentor to Kevin, an overbearing novice hitman played with delightful flair by Game of Thrones’ Jack Gleeson. Only there’s an ideological void where the movie’s subtext ought to be. In the Land of Saints and Sinners may be set during the Troubles, and some of its dialogue may gesture towards political metaphor—Finbar refers to being locked in a cycle of vengeance with Doireann, though it seldom feels that way—but the film is completely disengaged from any political perspective, beyond presenting its IRA quartet as ruthless, two-dimensional killers.

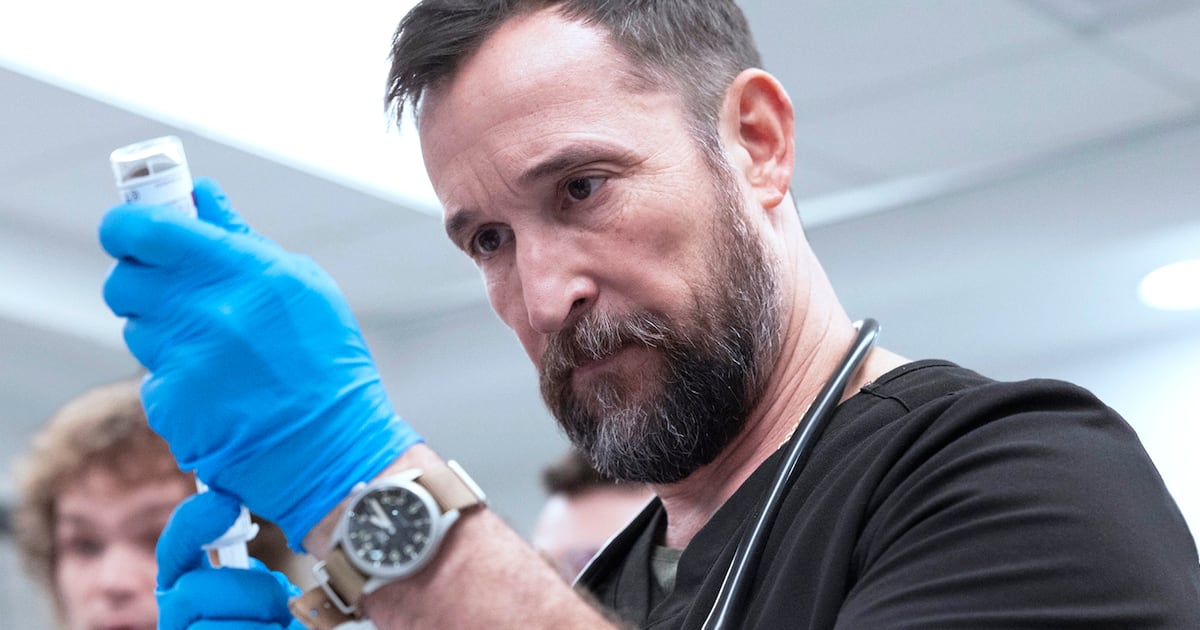

At least the leads are consistently captivating. The film may have dispiritingly little to say about Doireann, but Condon makes a meal out of these scant ingredients. She’s utterly terrifying at times. Meanwhile, Neeson—whose career pivoted to these sort of burdened roles after a family tragedy in 2009—proves yet again that his face is the perfect canvas for anyone hoping to paint the tale of a man afflicted by death. (He also plays a widowed assassin in Lorenz’s The Marksman).

The filmmaking is largely unobtrusive, with the kind of broad, straightforward blocking and dramatic presentation that allows the actors to do all the talking. Except for a key scene that ramps up the tension near the end, the camera rarely enhances any of the performances, but it also rarely needs to. Lorenz knows just when to get out of the way, and in the process, he crafts an enjoyable airplane movie. That may seem like a backhanded compliment—the film has plenty of flaws when it comes to political optics—but when a “turn your brain off” movie works, it works like a charm.