Robert Eggers crafts ancient fairy tales drenched in torment and madness, and The Northman proves a fable of fire, blood and fury that expands the ferocious scale of his folk-horror cinema. Fuming with a rage so fearsome as to be otherworldly, the latest from the director of The Witch and The Lighthouse is at once a kindred spirit to those masterful predecessors and a turning point for the 38-year-old auteur, employing his trademark aesthetics and atmosphere for a more streamlined and archetypal story about a Viking prince on a quest for revenge against his treacherous uncle. Coated in dirt and muck and stained in swaths of crimson, it’s a grand and gruesome epic of destiny and decapitations, malevolence and magic—a death-metal ode to honor, retribution and sacrifice that casts payback in a surprisingly, and thrillingly, positive light.

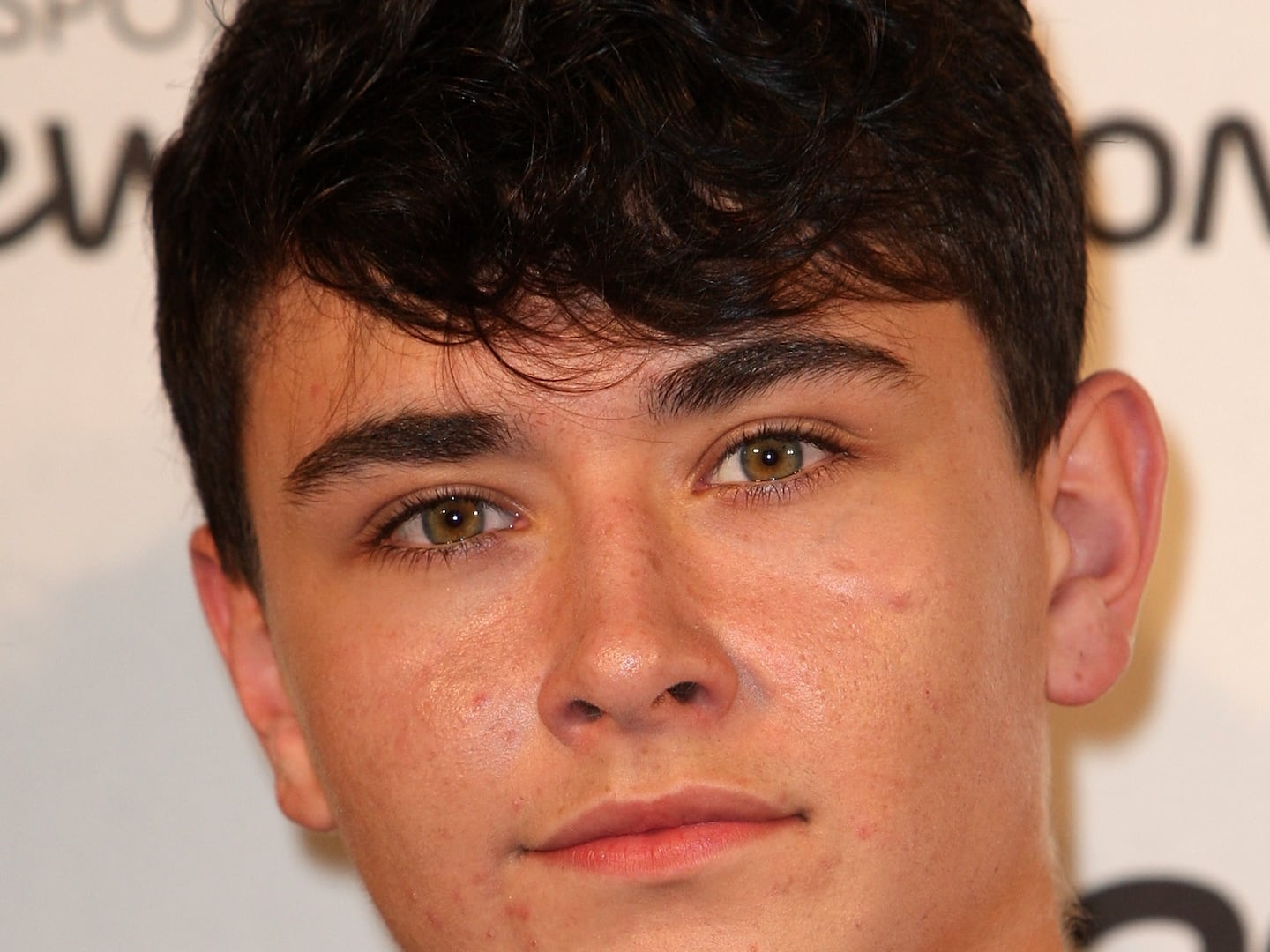

With ripped abs and a cold, single-minded stare, Amleth (Alexander Skarsgård) is a man without a home or a clan, living among other Viking marauders who believe themselves to be lycanthropic beasts, howling at the moon like wolves and roaring at the sky like bears around blazing campfires. By the time we meet Amleth, we already know what’s made him so feral, courtesy of an introductory 895 AD passage that focuses on the ordeal suffered by the young Amleth (Oscar Novak) years earlier, when his father King Aurvandill (Ethan Hawke) returned home from battle to his Queen Gudrún (Nicole Kidman) and his brother Fjölnir (Claes Bang). Aurvandill is an aloof monarch to his wife but he exhibits rugged affection for his son, taking him to a forest temple where—under the guidance of court jester and spiritual shaman Heimir the Fool (Willem Dafoe)—they participate in a hallucinatory pagan ritual that links man to animal and allows Amleth to spy the Tree of Kings, which resides within their bloodline.

Though Amleth is heir to the throne, his world is shattered when, following this mind-melting experience, his father is set upon and slain by Fjölnir in an act of betrayal that will forever shape the prince’s path. The Northman’s set-up is pure Conan the Barbarian, replete with heads being separated from shoulders by mighty blades in the snowy woods, and like John Milius’ 1982 gem, Eggers’ film carries itself like a legend, full of hulking mass and import (the only nod to historical reality is a brief mention of King Harald Fairhair). From the armor and fur cloaks worn by Aurvandill, to the mist and smoke that cover this chilly landscape, to the crunching footsteps of the men and horses that traverse it, the action moves like a lumbering goliath, trudging onward toward ruin, mayhem and tragedy that’s as inevitable as the rotation of the Earth. There’s mammoth weight to this saga, and once it shifts its attention to Skarsgård’s grown Amleth, that heft is embodied by its protagonist, who screams and bellows with a vehemence that’s also expressed through bludgeoning combat.

From the desolate look on his face, it’s apparent that Amleth’s days of killing and pillaging are only temporary, and they conclude following an encounter with a blind Seeress (Björk, as mesmerizingly weird and chilling as expected) who prophecies that his fate is to avenge his father’s assassination on a fiery lake with a mythic steel sword, at which point a maiden king will assume the crown. This compels Amleth to join up with a group of slaves bound for the Icelandic homestead of Fjölnir, who despite his fratricidal perfidy has been reduced to living life as a farmer. In this group, Amleth meets Olga (Anya Taylor-Joy), an imprisoned woman who speaks in outmoded tongues to the god of the soil, and together, they conspire to achieve Amleth’s ends, along the way falling in love.

Amleth seeks to save his mother and murder his uncle, and he takes a slow-burn approach to serving Fjölnir his just deserts. Fjölnir doesn’t know Amleth’s true identity, and he and his arrogant and unworthy sons treat Amleth as a lowly piece of property. Much of The Northman’s middle passages involve the Viking’s acts of sly insurgence and stealthy terror, including dismembering two guards and impaling them against a hut in the shape of a steed. Everything builds toward inevitable hellfire and doom, and Eggers stages it with a methodical, head-down resolve that echoes the determination of Amleth, whom the magnetic Skarsgård turns into a figure of obsessive purpose, convinced that felling his disloyal uncle and liberating his mom are his sole reasons for existing, and will grant him the peace and freedom he’s never known.

The Northman immerses itself in a pit of anguish and anger, equal parts mystical Valkyrie-and-Valhalla dreams and gritty real-world nightmares, and Eggers evokes it with his usual array of silky and muscular camerawork and gray-black imagery (via cinematographer Jarin Blaschke), as well as a Robin Carolan and Sebastian Gainsborough score of thunderous malice (here, punctuated by bagpipes). His cast is highly attuned to the dour and demented atmosphere he’s conjured; a merciless Bang and cruel Kidman tap into the ugliness of this bygone world, Taylor-Joy radiates holy hope as the sole person committed to Amleth’s enterprise, and Dafoe exudes a familiar brand of maniacal deviance. Noseless soldiers, human sacrifices, undead warrior kings and packs of wolves and birds (the latter imbued, as in The Lighthouse, with menacing spiritual power) are additional elements of this grim stew, which Eggers transforms into a primeval portrait of the desire to wrathfully redress past wrongs that can never be undone.

Amleth executes his mission with ghastly resolution, and if The Northman boasts less of the delirious, spiraling lunacy of The Lighthouse, it makes up for it with broad-shouldered, battering-ram savagery shrouded in flickering gloom. His tableaus of agony and wonder enhanced by unsettling CGI, Eggers spins a yarn that’s 1,000 years old and yet pulses with timeless ire, his story locating the sweet spot where the archaic and the new seamlessly intertwine. Moreover, while his film adheres to the tenets of its chosen genre, it eschews the moralizing that often defines it, instead embracing the notion that vengeance can fuel a righteous cause rather than merely be an annihilating force that destroys the vengeful. There’s horror and insanity in The Northman’s vision of predestined reckonings, and also beauty in its final contention that some ordained undertakings are worth the blistering, brutal cost.