It’s hard to explain a show like Industry to the uninitiated without mentioning Succession. And yet, I’m a little embarrassed when I name-drop the satire about a dysfunctional, wealthy family who run a conservative media conglomerate (nothing to do with Gen-Z bankers) to Industry co-creators Mickey Down and Konrad Kay when I speak to them over Zoom.

Both HBO shows—mostly comparable in that they feature mean, chatty businesspeople in puffer vests and have British creators—initially arrived on the cable network to little fanfare but slowly garnered favor on Media Twitter and among critics. Succession, which has now won multiple Emmys, is arguably the biggest get for the network, along with Euphoria (another show Industry resembles in certain aspects). Still, pointing out the similarity sounds a bit reductive.

“If Industry had the same arc [as Succession], me and Mickey would be quite happy,” Kay laughs.

Then I remember that Down and Kay, Industry’s sole writers, make a quick but explicit reference to Succession in Season 2’s penultimate episode, revealing that they're both in on the joke or maybe just manifesting.

Luckily for the creative duo, Industry's sophomore season, which premiered on Monday, is as compelling and tweet-worthy as its first, likely to lure more eyeballs and strengthen the Industry hive. The series picks up three years into Harper Stern (Myha’la Herrold), Yasmin Kara-Hanani (Marisa Abela) and Robert Spearing’s (Harry Lawtey) tenures as full-time employees at Pierpoint & Co. after competing for permanent positions at the London bank in Season 1.

Harper and Yasmin are particularly determined to move up the Pierpoint ladder with little concern for the people they cross along the way, including each other. In the premiere, we find Harper submerged in a booze-filled, quarantine funk that’s causing tension between her and her domineering supervisor Eric Tao (Ken Leung). She spots an opportunity to bounce back after encountering an illustrious potential client named Steve Bloom (Jay Duplass), who immediately signals trouble.

Meanwhile, Yasmin starts to long for more than her role on the foreign exchange desk while also becoming oddly resentful of a younger female hire. And just when we think she’s escaped her former manager Kenny’s (Conor MacNeill) reign of terror, he resurfaces to give her some passive-aggressive faux apology he learned in therapy.

This is just a small taste of Season 2’s drama, of course. The entire season is an intricate web of storylines, emotional arcs, and excursions that careen from jaw-dropping to devastating, but are all coherent and thoughtfully executed.

A series with such an incisive, precise view on banking (and plenty of brain-wracking financial jargon) could only be written by people with firsthand experience like Down and Kay, who left the finance industry in their mid-twenties for careers in film and television.

The writing and producing team spoke to The Daily Beast about Industry becoming a sleeper hit, the challenges of writing a second season, and the show’s dominant female perspective.

First off, as someone who’s tweeted a lot about Industry and seen the show slowly become this hit online, I’m curious what it was like seeing the response to Season 1.

Down: It’s lovely. It’s wonderful. We were blown away by the response. We had absolutely no idea how it was going to land. And obviously, it was very difficult in Season 1 to actually know how it landed because [of] the pandemic. Everyone was at home. We had no sort of fanfare. There was no premiere. We didn’t see anyone in-person. For months, we didn’t see any of the cast. We didn’t see each other. We did all the editing remotely.

I mean, I love that you say that everyone’s talking about it, because that actually gets me excited. I’ve got absolutely no idea how many people have seen it or watched it. I felt like there was a little bit of a bump, in terms of its cultural significance, as we say, a few months after it came out. I felt like—especially people in the U.S.—were suddenly saying, like, “Oh, I’ve seen your show now.” “Oh, people were talking about your show.”

Kay: It’s very heartening to see people take to it. And it’s very nice just to have something land in the world and for people to be evangelical about it. It’s very exciting.

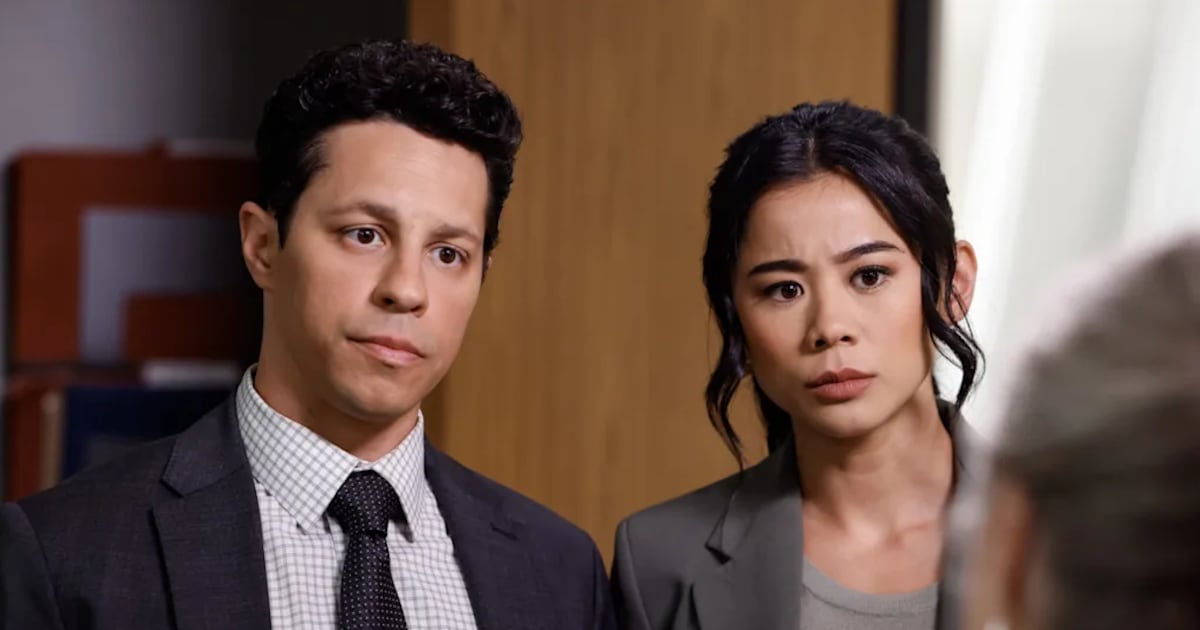

Industry co-showrunners Mickey Down and Konrad Kay

HBODid you find writing the second season more of a challenge? I feel like, with Season 1, the structure was kind of laid out for you.

Down: Because we didn’t have the structure of the RIF day and surviving, like, the actual original premise of the show, we were like, “We have to be really rigorous in the way that we write the show.” We had a proper HBO person who linked us with Jami O’Brien, who’s the sort of veteran showrunner-writer. She was outstanding in the way that she basically had to run the show and create a serialized story of eight hours of TV.

As much as I love the first season and think it’s, in many ways, very successful and satisfying and works, I do think the one thing that it doesn’t have is an iron-rod story through the whole thing that begins in the first episode and ends in the last. Criticism of the show, the first season, would be like, the main story point, which is Eric locking Harper in that room, happens four or five episodes in. And then all the fallout of that is the rest of the season. I feel like we wanted to start at 80 miles per hour this season and just have a storyline that took us through the whole thing. And I think that was the biggest challenge.

Kay: We were quite intimidated, obviously, by doing something for HBO for the first time. And I think what it made us do is stabilize us on our writing and our ideas a little bit, and my and Mickey’s ideas in Season 2 were like, “What if every scene we just pitched as our fastball rather than kind of pull our punches?” And I think the tension of Season 1, which was so much a function of Nathan [Micay’s] score and some of the direction and some of the writing—we just doubled down on that. I feel like I always say this. But more happens in episodes one and two of Season 2 in the whole of Season 1.

You mentioned Jami O’Brien. How do you think her perspective lended itself to this season, which predominantly focuses on the women at Pierpoint?

Down: Really good question. I feel it was probably an organic evolution. I mean, obviously the show was focused around Harper in Season 1. I feel like it was the privilege of having Marisa on the show, that we just had to give her more because we love her character. We love writing for her. We think she’s a linchpin of the show.

I feel like Jami’s presence on the show probably pushed their plots towards that. And I feel like—she won’t mind me saying this—Jami is older than us. And we want to see more of Eric as well. We want to see Eric’s perspective. We wanted the perspective of someone that had been in the business a bit longer. And Jami was really, really supportive in the fact that we have these ideas. And then she would push us towards the best versions of stuff, constantly putting obstacles in front of obstacles we can hopefully scale. And I feel like it was an organic shift towards [Harper and Yasmin].

We meet Steve Bloom a.k.a Mr. COVID in the premiere. How did Jay Duplass get cast in this role? I think he’s so good.

Down: The character on the page was a bit different. He was a little bit older originally. He was a little bit more stern, more of a sort of typical finance character. He didn’t have the playfulness or the sort of sensitivity that Jay usually brings to his characters. We hadn’t even thought about someone like Jay, and then the casting team were like, “Jay Duplass.” And it was one of those moments when you’re like, “That’s interesting.” And then you can’t get it out of your head. So me and Konrad started becoming obsessed with the idea of him playing it and had no idea how he was going to react to it. He even said in the New Yorker interview [that] he hadn’t seen the show. Someone sent him the first season. He watched the first couple of episodes, was like, “What’s this?” Then he was hooked.

How much fun did you have writing his dialogue? The way he talks is so grating and condescending but in a very specific way.

Down: We loved writing him. And we were writing the back half of the season while we started filming it. So once we saw his performance, it became even easier to write.

Speaking of Mr. COVID, I was wondering how much thought went into whether or not to depict the pandemic this season.

Kay: We had two concurrent thoughts. One was, we cannot not write about a contemporary workplace and not acknowledge it because of how big a thing it was in the grand scheme of things. And then the secondary thought was, will anybody want to watch a show that’s really about COVID? The success of the first season, in some ways, was that it was this escapist fantasy, especially during COVID. So what we thought was, we had a rule, which was like, it would exist in the universe of the show. The characters will have a psychological response to it. There’ll be some masks. There’ll be some hand sanitizer. But the actual present-day plot would only really be impacted by it peripherally so that it never felt like a story engine but it could have a psychological impact on the characters.

Yasmin has a very different isolation period than Harper. She gets heavily into drugs. She leans on her privilege. She just spends a lot of time in people’s houses having a really good summer, she says. Harper’s been using it as an excuse to not see people, which is very much in keeping with Harper. Robert uses it as an excuse to clean up his act and be sober. Kenny’s gone to rehab. All of these people have had different reactions to it. But it was important for us that it didn’t drive plot in the present-day story because we thought people would be a bit fatigued by the whole thing.

Myha'la Herrold stars as Harper Stern in Industry Season 2

HBOSpeaking of Kenny, he shows up again toward the end of the premiere in a pretty startling way. He’s come back from rehab. And he’s remorseful to Yasmin, but there’s still something off about his apology.

Kay: It’s that it’s about him, and it’s not about her. I think that was the thing that we kept coming back to, is like, how can an apology become oppressive? And that’s kind of his apologizing to her. As Mickey says, it’s performative. It’s about him. And he’s constantly going back to the well of, “I’ve changed. I go to therapy. Look at me. Look at me.”

Down: We were fascinated by his character, firstly, because it feels so true to that world but also incredibly universal. I mean, I feel like many women have had an experience similar to the one that Yasmin had under Kenny. And we thought, if he’s coming back, he can’t do the same thing again. He can’t just harass her the same way. He’s been admonished for that. How does someone who has been admonished for that respond to it? And is that response actually genuine? And I think the thing you’re thinking—and I hope the audience is getting—is the ambiguity of how genuine this sort of conversion is. This is maybe really reductive, but he’s still a cunt. He’s lording over in a slightly different way. He has a sort of performative change. And he’s patronizing. And it’s artifice.