Borat, The Rehearsal, and Paul T. Goldman have pioneered a distinctly modern brand of comedy in which fact and fiction are knottily intertwined. On the surface, Jury Duty seems to be following their lead, given that it’s a long-form ruse staged for the benefit (or is it punishment?) of one hoodwinked participant. Amazon Freevee’s eight-part series (premiering April 7), however, is less a boundary-pushing affair with pointed things on its mind than an empty Candid Camera throwback (by way of The Truman Show) that’s stretched to unrewarding lengths. It’s proof that what Sacha Baron Cohen and Nathan Fielder do isn’t easily replicated.

Jury Duty’s mark is Ronald Gladden, a 29-year-old solar panel contractor who arrives at Huntington Park Superior Court in Los Angeles County without a clue about the scam being perpetrated by co-creators Lee Eisenberg and Gene Stupnitsky, showrunner Cody Heller and director Jake Szymanski. That ruse: Everything taking place is a sham, and everyone involved is an actor. Ronald is the only “real” person in this made-up situation, which affords an opportunity to gauge his tolerance for nonsense.

That begins with an underwhelmingly wannabe-wacky civil trial concerning business owner Jacquiline Hilgrove, who’s suing former employee Trevor Morris for showing up to her factory drunk and high, and allegedly peeing and defecating on an enormous batch of custom shirts that had been ordered for an important influencer’s big event.

The proceedings are presided over by considerate Judge Alan Rosen, who claims that after a 38-year career, this is his “swan song,” and friendly bailiff Nikki Wilder. Before opening arguments can begin, however, Ronald must first be selected for the 12-person jury—a process during which he meets a host of oddballs, including James Marsden, playing himself, who bristles at having to serve when he’s on the cusp of landing a part in a movie called “Lone Pine” from an illustrious (unnamed) director. Ronald recognizes the actor from the start, although he can’t name many of his notable roles (aside from X-Men), thus resulting in some weak banter about Sonic the Hedgehog that never approaches the awkward hilarity for which it strives.

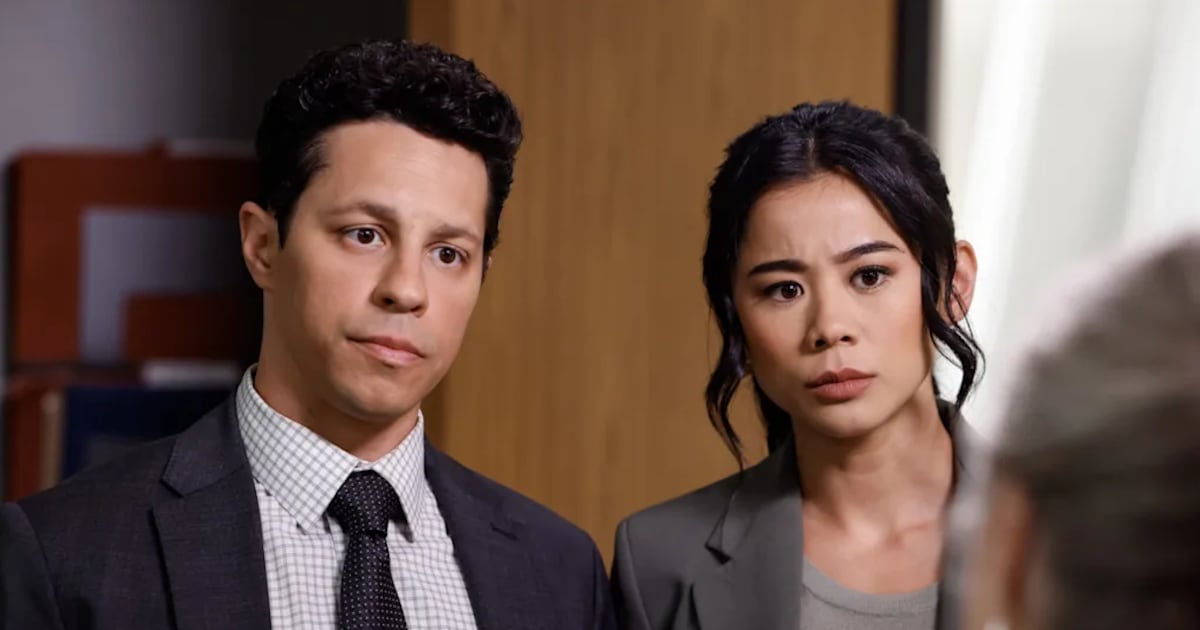

The same, unfortunately, can be said about Ronald’s interactions with his other (fake) conscripts, all of whom are supposed to be colorfully weird and yet are prevented from behaving too outlandishly lest they expose themselves as phonies. Small business owner Ken Hyun, rideshare driver Noah Price and retail associate Jeannie Abruzzo are all distinctive and eccentric but not loopy enough to generate real laughs. The only truly inspired misfit is quality control assistant Todd Gregory, who enters court on day one wearing a cantina backpack through which he drinks liquids and emulsified solids, and who later appears sporting “chair pants” (or as he refers to them, “chants”): a homemade invention that combines crutches, knee pads and a harness, and allows him to sit down at any moment.

Todd’s gizmos are the closest that Jury Duty gets to legitimate absurdity, as the series is constantly pulling its punches in order to keep Ronald in the dark. While he admits that things are “crazy” (and “like a reality TV show”), what’s presented on-screen is rather tepid. Thanks to Marsden orchestrating a paparazzi photoshoot, the judge sequesters the entire jury for the duration of the trial, meaning they have to live in a hotel and disconnect from the outside world (i.e., no cell phones). This is certainly a canny way to confine everyone in a controllable bubble. What ensues, though, is ho-hum, from the group struggling to figure out what lunch orders to place and playing video games in their down time, to Ronald—who’s named foreperson in order to give him added responsibility—endeavoring to prod elderly juror Barbara awake during testimony.

Over the course of Jury Duty’s two weeks, Ronald is repeatedly presented with strange scenarios and forced to give his opinion, such as Noah’s admission that his girlfriend Heidi has gone on a vacation with a friend named Cody who might be a male romantic interest. The problem with such set-ups is two-fold. First, none of these dilemmas are particularly amusing in and of themselves. Second, their larger purpose is never clear. Eisenberg and Stupnitsky’s series seems to be testing Ronald to see if he’s a good guy…and nothing more. There’s no grander point to the scheme other than to measure the protagonist’s patience and virtue—hardly a fascinating subject considering that Ronald comes across as merely an everyman who takes his jury responsibility about as seriously as you’d expect.

In its last episode, Jury Duty reveals that Ronald was originally selected from a pool of applicants who were informed that they’d be partaking in a documentary about the judicial system. It’s clear that Ronald was chosen because he’s an easygoing and conscientious individual, and the series confirms that through a variety of incidents in which he refuses to rat out his colleagues for their misbehavior (such as pleasuring themselves in the bathroom), takes the blame for their indiscretions (like Marsden clogging a toilet), and empathetically brings them together as a unified team (during final deliberations). Always working toward the greater good, doesn’t do more than guffaw and make astonished bug-eyed expressions when confronted with his fellow jurors’ bizarreness, and the ostensible idea is that this proves he’s a shining example of decency, compassion and civic duty.

That he is, and yet the overriding question hovering over Jury Duty remains: Is that all there is to this stunt? The series finale pulls back the curtain for both viewers and Ronald, revealing the myriad production mechanisms employed to pull off this venture, and it’s difficult not to think that it was a lot of time and energy wasted on a rather mild and unilluminating endeavor. Ronald’s conduct throughout the trial is agreeable and tolerant, and in an out-of-the-blue closing twist, he’s literally rewarded for it (and dubbed a “hero,” no less). His ordeal, however, merely resonates as a protracted hidden-camera ploy with nothing interesting—or, most frustrating of all, funny—to say about anything.

Liked this review? Sign up to get our weekly See Skip newsletter every Tuesday and find out what new shows and movies are worth watching, and which aren’t.