The steamiest movie of the season is also its most uncomfortable. Last Summer, which hits theaters July 28, is the first film in a decade from provocative French director Catherine Breillat. With Last Summer, she adapts 2019’s Danish film Queen of Hearts with a suspenseful sexiness that’s hard to shake. The story of a quasi-incestuous May-December romance that threatens to destroy a well-to-do family, it’s a drama expertly modulated to raise both eyebrows and pulse rates, led by a superb Léa Drucker performance that’s rooted in uncontrollable self-destructive passions and intense self-preservation instincts.

Last Summer introduces us to Anne (Drucker) grilling a teenage girl about her drinking on a given night, as well as her carnal proclivities with boys. Though this initially seems like a mother-daughter scolding, it’s slowly revealed to be a lawyer-client back-and-forth; Anne is an attorney who specializes in counseling kids in peril. Her own adopted Asian daughters Serena (Serena Hu) and Angela (Angela Chen) are far more stable than the children with whom she works, and her home life with them and husband Pierre (Olivier Rabourdin) is a luxurious and happy one.

That all changes, however, when Pierre receives a call from his ex-wife indicating that his 17-year-old son Théo (Samuel Kircher) has again gotten into trouble at school. In response, Théo comes to live with Anne and Pierre, despite the fact that the boy is bitterly estranged from his father, who was MIA during his upbringing.

Upon arriving, Théo lives up to his billing as a grade-A pain in the ass, leaving his clothes strewn all over the house for Anne to pick up, bristling at his elders, and caring more about wasting time on his phone and smoking inside than about obeying rules or being productive.

From the outset, Last Summer presents parenting as a form of quasi-warfare, not only between adults and their kids but between former spouses, as is underlined when Anne’s sister Mina (Clotilde Courau) chafes at her deadbeat ex for unexpectedly dropping off their son at her place of employment. Such male-female and interfamilial tensions are everywhere, such that even a playful judo match between Théo and one of his adolescent sisters (“I strangle all the boys” she says while pinning him) contributes to the mood of omnipresent hostility.

If antagonism bubbles beneath its placid surface, Last Summer is simultaneously energized by a strain of subtle sexual electricity. Be it a quick glimpse of Anne pulling a shirt over her bra, or recurring shots of characters’ feet (in and out of shoes), sensuality courses throughout these proceedings, thereby setting the table for the messiness to come.

Working from a script co-written by Pascal Bonitzer, Breillat suggests the interplay between her two primary concerns—parenthood and sex—during a scene in which Pierre slowly undresses and then climbs on top of Anne while discussing how Théo is “mean as hell.” Anne’s ensuing mid-lovemaking anecdote about having a crush on an older man when she was 14—whose “thin parchment skin” both disgusted and fascinated her—adds an extra age-related element to this fraught mix.

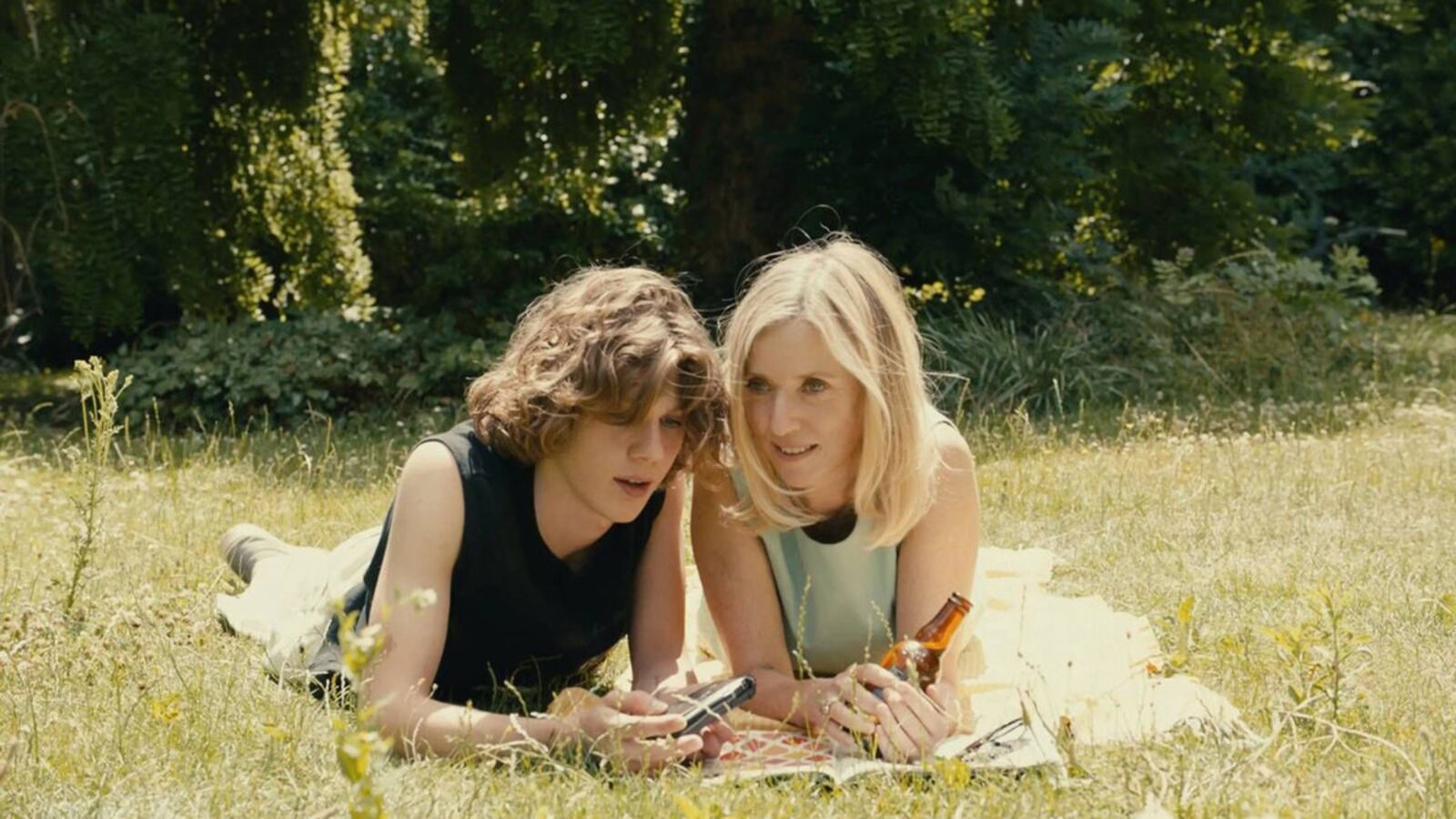

Anne claims she’s a “gerontophile” and that “normopaths” bore her, but her subsequent actions indicate that merely one of those statements is really true. Ditching a dinner party to go on a walk and have a drink with Théo at a local café, Anne is clearly smitten with the way the floppy-haired, oft-shirtless boy cocks his head and gazes at her with playful come-hither lust. When, at a later date, she joins him on his bed to check out the anime movie he’s watching on his phone, they kiss. Sex follows, with Breillat’s camera zooming into Anne’s ecstatic eyes-closed face.

This is a mistake and Anne knows it. Nonetheless, their affair continues, complete with her confessing secrets to him on audio tape about her past abortion (which is the reason she’s infertile and adopted Serena and Angela). Only after they’re caught by someone close to them does Anne have a moment of clarity and attempt to halt things before they truly explode. Yet as she soon learns, taming the heart (and the libido) proves easier said than done.

During a private conversation, Anne admits to Théo that her biggest fear isn’t just that everything will disappear, but that she might make it all vanish, because the sole thing worse than calamity is the anticipation that precedes it. This impulse is at the root of Anne’s compulsion, and yet Last Summer affords no easy answers regarding its protagonist, who responds to being found out by cannily manipulating the truth, and her thorny domestic circumstances, to her advantage.

The film pulsates with erotic desire and throbs with the fear of being discovered, which is so severe that—as Anne believes—it’s almost a relief when there’s nothing, and nowhere, left to hide. Except, of course, that there’s always something worth concealing, and Anne eventually finds herself caught between setting fire to her life and putting out the flames.

Last Summer doesn’t care about condemnation; its focus is on the wayward impulses driving Anne forward in the face of obvious catastrophic consequences, and Drucker sells her plight with a steeliness that’s laced with layers of arrogance, hypocrisy, and recklessness.

In various close-ups, Drucker segues sharply from confidence to caution to unbridled carelessness and back again, and her poise and precision are key to the film’s intriguing dynamics. To an even greater extent than Théo, whose behavior is grounded in a more immature longing for compassion and vengeance, she’s a figure wracked by warring instincts and interests, and Drucker evokes her contradictions with a meticulousness that buoys the material.

What’s ultimately most exciting about Last Summer is that it refuses to indulge in comforting tsk-tsk moralizing about its characters, whose conduct—whether foolish, selfish, reprehensible and/or mean—is allowed to speak for itself, all as they rapidly circle a figurative drain of their own construction. A decade away from the movies, Breillat remains a masterful artist with a keen eye for human hungers, cruelties, and crises, and she orchestrates her latest with patience and perceptiveness. A startling portrait of irrepressible forces and unwise choices, it’s proof that the 75-year-old auteur has been gone too long.