When The Favourite arrived in 2018, it ushered the period drama into a deliciously profane new era. Undoing expectations established by the prim-and-proper costume dramas of the past, the movie’s scheming, swearing, and sexual innuendos made it a cinematic phenomenon—and paved the way for the likes of the steamy Regency rom-com Bridgerton and the spiky, no-holds-barred humor of The Great.

In terms of raunchiness, though, Mary & George is the period drama to rule them all. In its two titular leads’ cutthroat world, it’s significantly not just strategic marriages that help get you ahead, but sex. And in this instance, it’s sex with a refreshingly out-and-proud king.

Mary & George is consistently unabashed about gay sex—or any sex, for that matter. But it’s more than just that; it’s also an antidote to the staid period dramas of the past. Out of every straight-up Austen adaptation or Austen-adjacent drama (right up to Bridgerton), there has often arisen a misplaced nostalgia for archaic structures pertaining to courtship, marriage and romance. But in King James’ court, heterosexuality and monogamy are—thankfully—not the norms. It’s a refreshing change, one that more of its ilk stand to learn from.

[Warning: Spoilers for Mary & George follow.]

Based on the true story of Mary Villiers (Julianne Moore) and her son George (Nicholas Galitzine), the Starz series’ first episodes see the eligible young man baptized into society by way of orgies and discovering his bisexuality. Upon his return, the mother-and-son duo connive to ingratiate themselves with King James I (Tony Curran) by inserting George into—where else?—the royal bedchamber. After three episodes so far of Succession-level maneuvering and backstabbing—sometimes literal—its latest episode is the most scintillating and salacious yet.

In Episode 4, King James and George—his new right-hand man, now that the nefarious Earl of Somerset (Laurie Davidson) has been cleared out of the way—head to Scotland. While fearing the king’s interest in him is waning (the king has a never-ending supply of men vying for his attention), George’s own interest is piqued by the Earl of Somerset’s cousin, Peter Carr (Dylan Brady). Not heeding his brother Kit’s warning (“Won’t King Sausage cut your head off you dip it in another pig?”), George quickly falls into the “wee bairn’s” embrace.

Sean Gilder as Sir Thomas Compton, Julianne Moore as Mary Villiers, and Nicholas Galitzine as George Villiers in Mary & George.

Rory Mulvey/StarzThis episode outright challenges the classic romantic notion that having both “true love” and more than one partner aren’t compatible. As the episode progresses, we learn of King James’ soulmate, Lord Lennox (known in real life as Esme Stewart), who, it turns out, was resented and eventually ousted by the rest of the king’s court, left to die a sad death alone in France. Even as the king waxes nostalgic about his lost love, it doesn’t lessen what he feels for George, and, as George becomes the king’s confidant, the romantic bond between them grows ever fiercer.

The king has eyes for far more boys than just George. In Episode 4 alone, there is uninhibited canoodling of the king by multiple men as all royal subjects gather at the dinner table, a fleeting attraction followed instantly by sex in the palace corridors, and one encounter which takes a particularly lethal turn.

There’s a ferocity in Mary & George enough to make the Borgias’ betrayals and violence look relatively tame. Though George is the king’s new favorite, being his bedfellow still proves to be treacherous, a minefield of mind games and mood changes. Case in point: George is rudely awakened by the king sinking his teeth into his arm. When, in the morning, King James happens upon George cowering, puppy-eyed, over his wound, he nuzzles his cut and coos, “Poor lamb—and poor wolf,” as if taking a bite of George’s flesh isn’t a totally wild thing to do.

Jacob McCarthy as Kit Villiers in Mary & George.

Mark Mainz/StarzEven George’s new paramour—amiable as he seems—has a nasty side. Peter takes George for what he promises will be a romantic outing to the remote tower where King James was kept captive while Lord Lennox was booted out of court. While Peter recounts the story, the pair begin to kiss, and Peter wraps his hands around George’s neck. Things sour when he begins to press down on George’s air pipes, revealing simultaneously that he is keen to avenge the death of his cousin. George gurgles and, still in the process of strangling him, Peter snaps: “Who the fuck do you think you’re talking to, you English slut?” And then, his head is blown off by Kit’s gun.

This is no Gosford Park or Howard’s End. Gone are the scandals behind closed doors; all sexual liaisons are right out in the open. Further, the show steers well clear of seeing sex as a transgression and—even as its protagonists do some undeniably bad things—resists judgment. Mary and George are not looked on as villains and, much like Peter Carr or the Earl of Somerset, are merely trying to fight their corner in a power-hungry climate.

Throughout this episode, nearly every sentence is interspersed with expletives—especially, it seems, ones that hadn’t yet been uttered by 1617. Its foul-mouthedness and brazen combination of murder and sex makes the series one of the most brilliantly rude, raunchy, and downright scandalizing period dramas to date. Like its recent predecessors, Mary & George recognizes that its characters are not distant figures from history, and they share many of today’s concerns, from quests for power to struggles with marginalized identities to the basic, constant battle to survive. A little embellishment with contemporary details makes no odds to me.

Nicholas Galitzine as George Villiers in Mary & George.

Rory Mulvey/StarzBetween Mary’s impressively wily plotting and George’s disadvantage as a second son (meaning he doesn’t stand to inherit his father’s fortune) motivating his seduction of King James, the show also manages to craft a knotty, nuanced portrayal of gendered power dynamics. It’s rare to see both men and women given a fair shot at autonomy in period drama; from Pride and Prejudice to Little Dorrit, melancholic storylines centered around women made to marry for money or reputation abound, and usually men are only ever seen as having the upper hand. (In fact, for better or worse, the men of Mary & George are as likely to be forced to marry as women.)

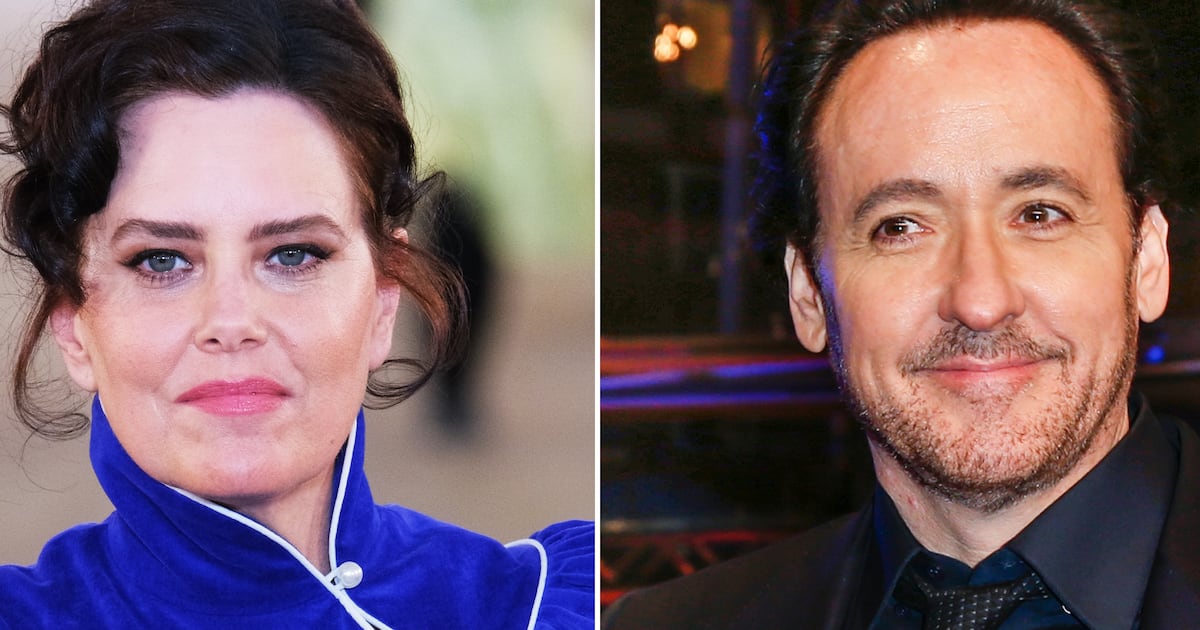

Tony Curran, Julianne Moore and Nicholas Galitzine in Mary & George.

Rory Mulvey/StarzWhile the show has no doubt angered period drama purists, Mary & George should set the bar for the genre going forwards. For too long, there has been a sore lack of horny queer stories from history told on screen. As contemporary queer stories have gradually started hitting the mainstream in other genres, our approach to dramatizing history has also been in need of a reevaluation. With its honesty, even-handedness, and biting humor, Mary & George has taken a big step in bringing the period drama up to date. And, really, the history speaks for itself.