Al Pacino can make a meal out of even the tiniest of morsels, and in Knox Goes Away, he feasts as a mysterious career criminal named Xavier who wears gold rings, leopard-print robes, and thinly framed glasses, as well as boasting a gravelly voice and big hair that’s so beautifully wavy one can easily imagine surfers gazing at it with drool hanging from their mouths. His character is also married to a Russian dancer decades his junior and prefers to eat Chinese food from take-out boxes for his 4:30 p.m. dinner in the bathtub, his wife painting her toenails by his side. He’s a supporting figure whose past is fleetingly implied but who, in looks and demeanor, clearly deserves a film all his own, and he’s unquestionably the most memorable part of this crime saga, which is about forgetting and, aptly, should—and likely will—be quickly forgotten.

The sophomore feature directed by and starring Michael Keaton, Knox Goes Away—premiering at this year’s Toronto International Film Festival—shines brightest whenever Pacino is on screen, his slumped body language suggesting preternatural confidence, playful cunning and world-weary exhaustion. Alas, the Oscar-winner is merely a small and ultimately peripheral component of Keaton’s behind-the-camera latest, whose guiding focus is John Knox (Keaton), a contract killer who earns a living assassinating strangers alongside his partner Tommy (Ray McKinnon). Together, they’re a yin-yang pair, as Tommy likes to discuss their targets and Knox does not, since he sees little point in giving thought to individuals who are about to cease to exist.

John’s disinterest in ruminating on the lives he’s ending speaks to his cold-blooded professionalism, yet Knox Goes Away is a rigged game that makes sure there’s never anything repugnant about its protagonist. Though he’s an unrepentant hitman, Knox only murders bad people, and as a Desert Storm army vet, he treats his job as simply another tour of duty behind enemy lines. Moreover, he’s an educated fellow who has two PhDs (in English and U.S. History) and once taught briefly at Bucknell. All of this earned him the nickname “Aristotle,” and as “the man of 1,000 books,” he likes to carry around paperback tomes wherever he goes, as well as lend some of the titles lining his apartment’s crowded shelves to Annie (Lela Loren), the Eastern European prostitute who’s visited him every Thursday afternoon for the past four years.

Knox is thus a typical sort of disingenuous crime-fiction creation: the erudite executioner with a conscience. As if Knox’s education, military service, and general charisma didn’t make him likable enough, Knox Goes Away strives to turn him sympathetic via a visit to a specialist who informs him that he has Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease, a rapidly developing form of dementia (think of it as Alzheimer’s disease in fast-forward) that’s responsible for the small mental lapses he’s begun exhibiting. Given mere weeks before his mind falls apart, Knox is told to immediately get his affairs in order. Rather than heed that advice, however, he joins Tommy on another hit, during which he’s plagued by blurry vision, beeping noises and brief blackouts—symptoms that beget temporary confusion and, in turn, a catastrophic, irreversible mistake.

This puts Knox in a perilous spot, and things go from bad to worse when he’s subsequently visited at home by Miles (James Marsden), the son who disowned him once he learned about his dad’s vocation. With his hand wrapped in a rag that’s covered in the same blood staining his shirt, Miles is a frantic mess, and the reason for his condition involves a misdeed he’s destined to be locked up for unless his estranged dad helps. Eager to reconcile, Knox agrees to provide assistance, the sole problem being that he’s no longer in reliable underworld-mastermind shape. Nonetheless, he soon sets a plan in motion, using a notepad to keep the orderly steps of his scheme clear and enlisting Xavier to periodically check in on him and guarantee that he hasn’t lost his carefully constructed thread.

Knox Goes Away isn’t the first (or fifth) genre effort to play with memory, although it might be the flattest. A far cry from the formally inventive Memento or the twisty-turny Total Recall, Keaton’s film is dramatically inert, its energy undercut by pedestrian visual framing, mundane staging and a wispy Alex Heffes score (mostly notable for its periodic mournful horns) that leaves great stretches of the action weighed down by dead air. Gregory Poirier’s script is neither original in concept nor exciting in execution, with Knox’s monotone quips landing with a thud and the “timely” jokes of the detectives on his trail—regarding modern slang like “IRL”—inspiring eyerolls. Title cards indicate what week it is in Knox’s path-to-deterioration, and recurring fades to black echo the hitman’s description of his ailment as akin to having a curtain go down on his psyche. Yet from start to finish, the material is crushingly lethargic.

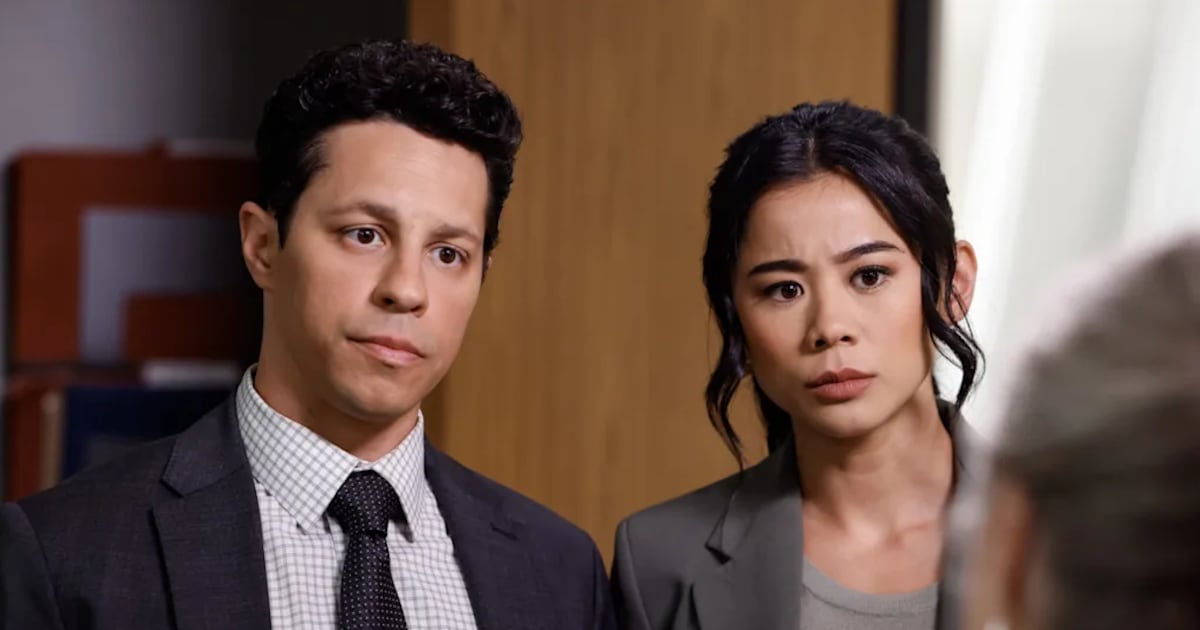

Michael Keaton in Knox Goes Away.

TIFFWorse, Knox Goes Away is obvious, telegraphing its trajectory early on when Knox talks to Annie about Casablanca’s sacrificial ending. The specific nature of Knox’s plan is kept largely secret but such haziness conceals nothing. Just as frustratingly, it says nothing about any larger ideas (about truth, guilt, regret, and reality) that might arise from the character’s befuddled state of affairs. Despite remarking that there are some things he looks forward to not remembering, Knox is merely another in a long line of Hollywood scoundrels with a heart of gold—or, at least, a sincere desire to atone for his sins and achieve redemption through martyrdom. Alas, since Knox himself admits that he’s doomed no matter what, his altruistic gestures are merely superficial, requiring no moral reckoning and, thus, no genuine transformation.

Keaton’s vacant stares and bewildered head shakes strive to imbue Knox with something resembling humanity. Knox Goes Away, however, is artificial to its core, thereby rendering its leading man’s efforts futile. By the time Marcia Gay Harden appears as Knox’s ex-wife, the film has already outed itself as a misbegotten pet project incapable of being salvaged by its talented maker or his illustrious cast—even the unfailingly charismatic Pacino.

Liked this review? Sign up to get our weekly See Skip newsletter every Tuesday and find out what new shows and movies are worth watching, and which aren’t.