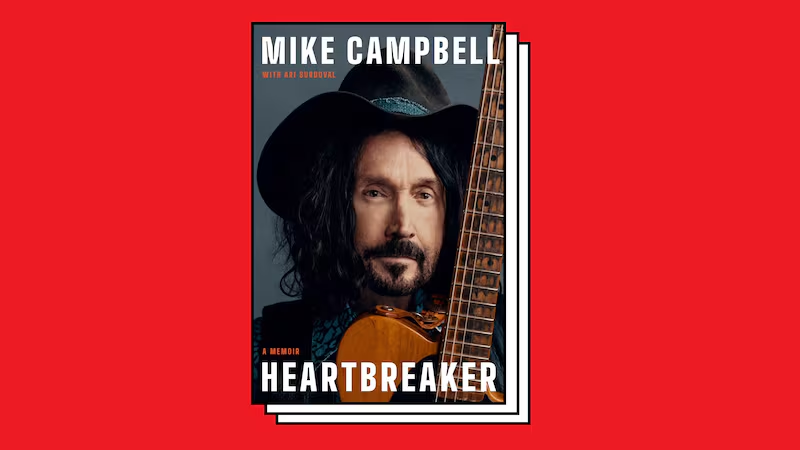

Tom Petty’s closest musical partner is lifting the lid on his untold life in an extraordinary book released Tuesday.

“Well, first of all, I told the truth. And second of all, I would take issue with anyone who says I didn’t put Tom on a pedestal,” guitarist Mike Campbell says to critics of the book, who say his insider’s tale of life in one of the 20th century’s most successful bands shares too many spicy details about his musical partner. “From my perspective, I talked about my friends, their good points and their bad points. But I think if you look closely at the book, in spite of my saying, ‘Well, this guy had this thing going on, it was rough,’ or whatever, I still put them, I think, on a pretty high pedestal. Tom, I’m constantly praising him.”

As the man Petty referred to each night on stage as his “co-captain,” and the only Heartbreaker to appear on all of the band’s albums, as well as all three of Petty’s solo records, Campbell no doubt had a front row seat to rock ‘n’ roll history during his storied career.

And it’s true, Campbell’s new memoir Heartbreaker is chock-full of stories that only someone on the inside of the rocket ride that Tom Petty & the Heartbreakers were on for over 40 years could tell, as well as revelations that even diehard fans of the band will find fascinating, heartbreaking, and sometimes even a bit shocking. But it’s also a story told with an abundance of love.

“I don’t think there’s anything salacious in the book at all,” Campbell adds. “I wouldn’t want that. Sure, there’s some stuff that’s a little personal, and it’s kind of a behind-the-curtain view of the inner workings of the Heartbreakers, but it’s a book deliberately focusing on the music and the relationships.”

Still, for even the most diehard fan, there’s plenty of weighty takeaways in Heartbreaker.

The stories of the band’s drug intake are both astonishing and terrifying.

“I’m no Goody Two-shoes, but I’m also no monster,” Campbell says with a knowing laugh.

Heartbreaker chronicles the well-known addiction struggles of both keyboardist Benmont Tench and bassist Howie Epstein, who died of a heroin overdose in 2002, after a long, slow decline. It also tells the story of Petty’s own drug troubles, which would eventually take his life. The memory of the band’s long-serving roadie Bugs calling up Campbell to ask him to check on Petty, when the icon was in the deepest throws of his own heroin addiction in the wake of his late-’90s divorce, is told in brutal, if sympathetic detail.

“There were long gaps between sessions. I hadn’t seen Tom for weeks when (our roadie) Bugs called and told me Tom wasn’t doing good. He said he didn’t know what to do.

‘How bad is he?’

‘Mike, he’s real bad.’

‘Bring him here. I’ll figure out something for him to do.’

I pulled up a simple rocker I had written for the album that had my temporary vocals on it. I set up a mic for him to replace them. But I wasn’t prepared for when Bugs brought him in. I was stunned. He shuffled in like an old man, slow and frail.”

As for Campbell’s own battles with drugs—mainly copious amounts of cocaine during the 1985 making of the band’s Southern Accents album—he remains more circumspect.

“I had my moments with the demon, and he taught me a lesson, and I learned from it, and I survived,” he says.

Petty ruled his band with an iron fist, which led to the band nearly imploding several times.

“Tom never doubted that we would make it. When all I knew was that I had nowhere to go, Tom knew we were going to the top. Nothing was going to stop him. He was little and he was skinny, but he could be unbreakable. He could withstand pressure like nobody I have ever seen. Tom Petty was one of the toughest people I have ever met, but it could make him hard on people. And then he would feel bad and get down on himself.”

Campbell recounts his continuing role as peacemaker in the band, frequently citing Petty’s response to being challenged on his decisions was a simple retort: “But I’m Tom Petty.”

“Sometimes he was a little difficult, but everybody is,” Campbell explains. “But at the end of the day, all of us knew, this guy is great.”

Money almost caused the end of the Heartbreakers on more than one occasion.

As Petty became more and more successful, the band was forced into a split of the money they were earning that broke down as 50 percent for Petty and the other 50 percent split between the rest of the band members. It was the cause of tremendous friction.

“Elliot (Roberts, the band’s co-manager at the time) said there would be a new distribution of live income. We have to make it fair, he said. From now on, we would split the money evenly. Fifty-fifty. Half for Tom, half for us. He didn’t stick around to take questions. There was nothing to talk about. It was not a negotiation. He thanked us for coming, wished us a good day, and left.

We sat there, steaming. Stan was livid.

“No. No way.”

‘Stan,’ I said.

‘Petty doesn’t even have the balls to show up. Fuck this. No way.’

‘Stan.’

‘There is no way I am taking this deal.’

‘Stan!’”

“We moved on or we would have broken up,” Campbell adds with a chuckle. “But yeah, I tried to help facilitate things. You know, ‘Dude, look at the facts here. What do you do? You play the drums and you have energy. You play keyboards. I play guitar. What does this guy do? Well, he writes the songs, he sings the songs, he brings the personality and performs to the crowd on stage. He also does a lot of the management. I think he’s working a lot harder than us and we shouldn’t get the same amount of money as him. And if you look at it that way, it’s a logical arrangement.’ And eventually that’s where we came to.”

Petty was “shocked” to learn he was the victim of arson.

On a sunny May morning in 1987, Petty’s Encino, California’s house went up in flames. “Tom said the house went up like a matchbox,” Campbell writes. “He grabbed a garden hose to fight it and the hose melted in his hand. His housekeeper ran out with her hair burning.”

“I assumed it was just a tragic, terrible accident. But the police told Tom it was arson. They took him to the back of the house, where a wooden staircase had been doused with a can of lighter fluid and set on fire. Tom was shocked.

The police asked Tom if he knew anybody who wanted to kill him. He said no, of course not. All over the country, people started confessing. People who couldn’t possibly have done it, but wanted the attention, or just wanted people to know that they would have done it if they could have. Whoever set the fire was never arrested.

It was a dark, disturbing time. Tom and his family lost almost everything. They got out with the clothes on their backs. Tom didn’t even have a pair of shoes."

The inside stories of working with Bob Dylan, Johnny Cash and George Harrison, make those legends feel both regular and otherworldly.

In Heartbreaker, Campbell recounts both the thrill of creating and performing with Dylan, Cash, and Harrison, as well as spending time with them in intimate and unassuming circumstances.

“It’s interesting, because people like that, who were such huge influences on me, and I do put on a pedestal in terms of inspiration, when you opportunity to meet them and or work with them, at first it’s a little like, ‘Oh, my God, it’s Johnny Cash,’” says Campbell. “But then you start working on the music, and you’re just musicians, trying to make this piece of music together. And you forget. It kind of fades away. And it’s just you and the musician and the human being there, on equal planes, so to speak.”

But a special place in Campbell’s heart is reserved for Harrison.

“George was very special,” Campbell says of his glowing portrait of the former-Beatle in Heartbreaker. “I was blown away that he treated me with such respect and kindness. He really thought I was good, and he went out of his way to be friendly with me and be open with me. I don’t know many people like that, famous or not, who are that sweet and generous.”

Mike Campbell was crucial in introducing producer Rick Rubin into Petty’s life, giving him one of his greatest career successes with the multi-platinum, universally lauded Wildflowers album, again almost hastening the end of the Heartbreakers.

“There was nothing on paper to indicate that Rick would be a good collaborator with Tom or that they shared any sort of musical sensibility. He didn’t seem particularly familiar with the fifteen years of Tom’s music that preceded Full Moon Fever.

Rick called me to introduce himself and told me he would love a chance to work with us. I listened as we talked, and I genuinely liked him. He was soft-spoken and thoughtful and intelligent, with a lot of love and passion for music. And he raved about Tom.

If we needed someone to focus all his energy on Tom and to inspire him, Rick was making a strong case for himself. I wasn’t sure, but I thought it could work.”

As for any internal conflict Petty’s periodic solo albums caused within the Heartbreakers, Campbell chalks it up to the power of the personalities and love within the band.

“Bands are so fragile,” he says. “The combination of these five people, there are so many things that can derail it: women, drugs, ego, money. The fact that we were able to keep it together as long as we did, I think, is a real testament to the fact that we all had pretty healthy egos, and to the love between us, and that we all loved the music more than anything else.”

Petty and Campbell were truly like brothers, with all the weird complications that sort of relationship entails, which made his tragic death in 2017 all the more intense.

“A hydra of grief gripped me—numbness and sadness and anger and resignation and disbelief—all jumbled, no rhyme, each feeling contradicting the next, some settling in for black days of emptiness and loneliness. I spent months of long, slow, sad days in the backyard, sitting with my dogs, quiet. Not writing, not playing. Not anything.”

“I processed my grief a while ago, but the brain is an interesting thing,” Campbell adds. “You pack away stuff that you don’t want to remember, but as you start reminiscing, it starts to flow again. So, writing the book was a fascinating experience because I’m not really a nostalgic person. I don’t like to think back, per se. I like to move forward. But there were a lot of memories, I don’t know where it came from, but they were stuck in there. And as soon as I touched on it, they came back into my mind. And I’m really glad that they did, because they were almost all built on love and respect, especially between me and Tom.”