Osgood Perkins (The Blackcoat’s Daughter, Gretel & Hansel) locates horror in unholy irrationality, and Longlegs is a serial killer thriller filtered through a nightmarish mélange of personal and cinematic memories. Dreamily recalling The Silence of the Lambs, Red Dragon, Zodiac, Seven, and Psycho—the last of which starred Perkins’ father Anthony—this saga of Satanic secrets and mommy dearests pulsates, from its chilling opening to its deviant finale, with nasty, misshapen malevolence.

Firmly establishing the writer/director as a genre craftsman with few equals, it’s a thriller that grows fouler and scarier with each step toward damnation, as well as providing an unforgettable showcase for Nicolas Cage as a zealous maniac unlike any other.

(Warning: Some spoilers ahead.)

In 1974, a young girl colors at her bedroom desk. Through her window, she spies a station wagon parked at the end of the driveway leading to her remote rural home. Donning a winter coat and a scarf, she investigates, and notices the shape of a person in the passenger seat.

Startled by a voice behind her, she turns and walks back across the yard, at which point she encounters a figure in white jeans, a matching denim jacket, long silver locks, and a seemingly deformed face whose lower half is all that Perkins reveals. This man says something about the girl’s birthday and wearing longlegs, and then bends down and shrieks in a burst of psychotic hysteria that’s as startling as the immediate appearance of the film’s title card.

Longlegs won’t contextualize this prologue until much later, since it promptly segues to Oregon in the 1990s, with FBI special agent Lee Harker (It Follows’ Maika Monroe) and her colleagues being ordered out into the field to knock on doors in search of a wanted criminal. In a cluster of cookie-cutter houses, Lee stares at rooftops and the sky as if in a daze, and a driveway entrance’s spraypainted “Visitor” marks her as an interloper in her target’s killing field.

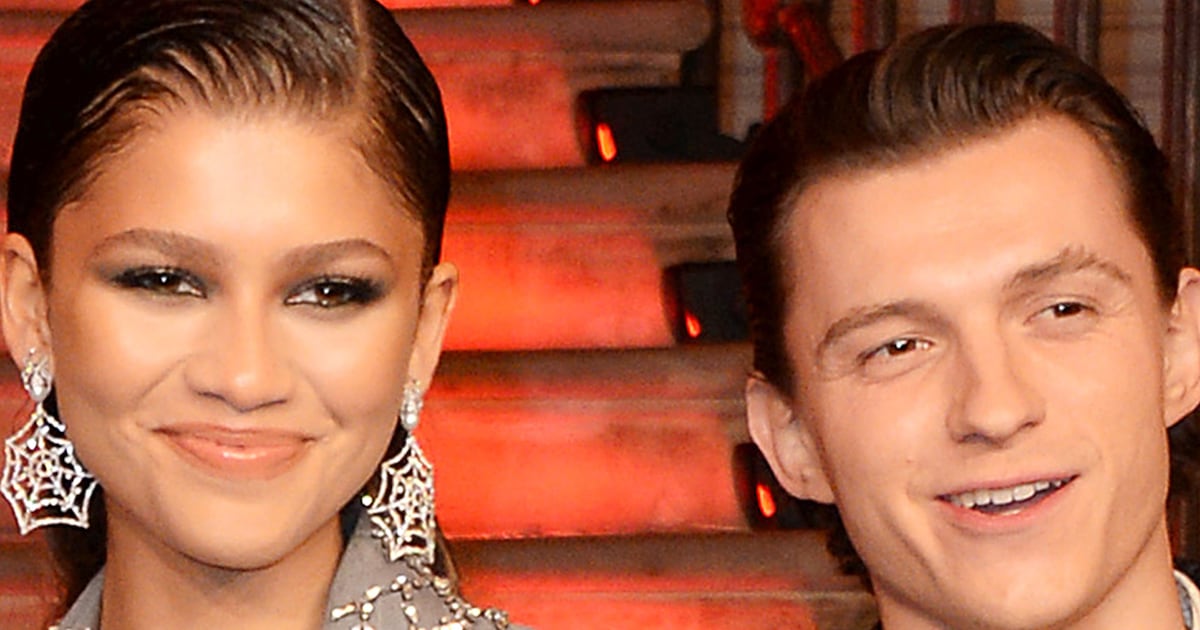

Nicolas Cage as Longlegs.

NEONThat impression is amplified when a “hunch” guides her to the abode they seek. In the aftermath of this episode, Harker is given an image-word association test by her superiors—which also involves guessing random computer-generated numbers—that identifies her as a semi-psychic who’s able to intuit things to a degree greater than her colleagues.

Because of this skill, Harker’s boss Agent Carter (Blair Underwood) recruits her for his inquiry into a 30-year-long series of murder-suicides committed by fathers against their wives, children, and themselves. In each case, including the most recent, the slayings take place on the 14th of a given month, which is the birthday of the clans’ daughters, and a note is left at the scene of the crime that’s written in ciphers save for its signature: Longlegs.

Despite these letters, there are no signs of forced entry and no physical evidence indicating the presence of another perpetrator. Thus, Harker initially surmises that perhaps they’re dealing with a quasi-Charles Manson who convinces his victims to carry out their homicidal deeds.

This strikes Carter as far-fetched and Harker’s own assumptions are quickly challenged when, one night at her Pacific Northwest log cabin residence (shades of Twin Peaks), she’s visited by Longlegs, who leaves her a birthday card that includes a key to his written code.

Sinister whispers on the wind foreshadow potential danger, and schizoid visions of snakes suggest devilish forces at play, and Perkins complements those devices with serpentine camerawork and expansive widescreen compositions that isolate his protagonist in the frame. Monroe inhabits Harker as a woman at a perpetual, icy remove, and her detachment from her environment and her fellow humans—such as Carter’s young daughter Ruby (Ava Kelders), to whose birthday party she’s invited—heightens the sense that an illogical and unstoppable evil lurks just around the corner.

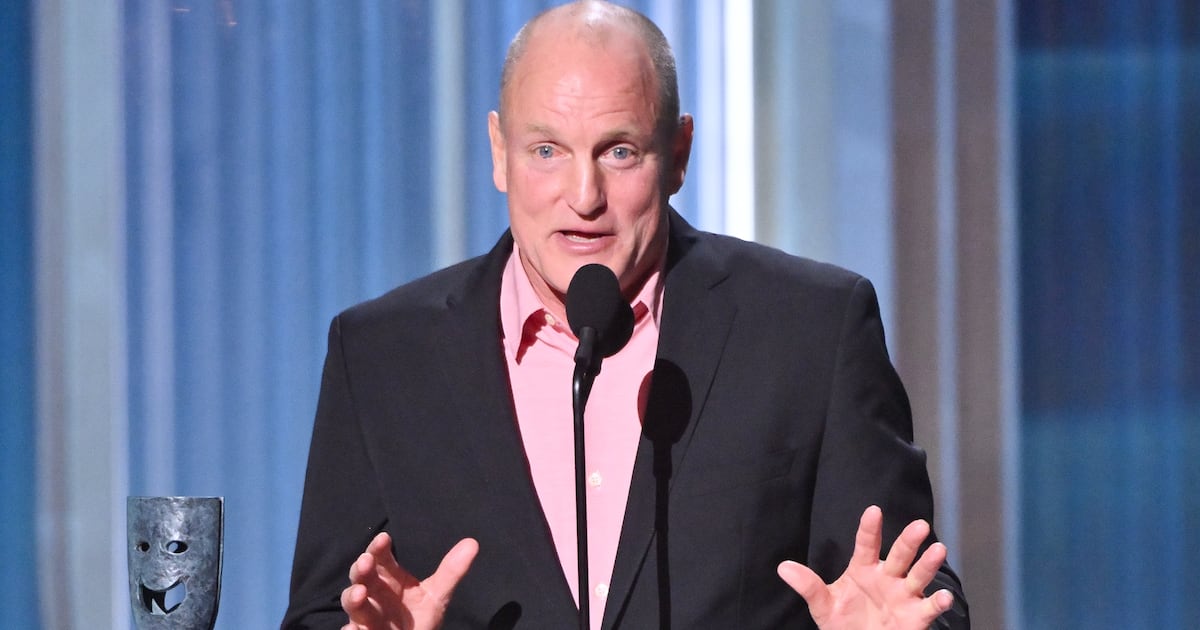

Maika Monroe in Longlegs.

NEON/NEONLonglegs affects a procedural pose but its mysteries are more profane, and its destination more insane, than its early going intimates. Harker’s sleuthing turns up archaic symbols and calendar-related patterns that, when put together, point toward ritualistic Satanic ugliness, all of which stands in stark contrast to the reminders by Harker’s mother Ruth (Alicia Witt) to steadfastly pray.

By their second phone call, it’s clear that something is amiss with Ruth, and a trip home—its interiors cramped by stacks of domestic detritus—reinforces that notion. Still, Harker has more pressing issues than her relative, such as a weird conversation with Longlegs’ lone survivor (Kiernan Shipka) and a preceding visit to the girl’s farm, where she and Carter discover a buried doll with one of the killer’s trademark missives.

The more Harker uncovers, the less she grasps, and Longlegs plays a similarly canny game, introducing a variety of familiar elements and then warping them into something strange and incomprehensible. Nothing makes total sense in the best way possible, with Perkins unnerving through opacity. Things don’t become lucid even once Harker and Carter get their hands on Longlegs and sit him down for an interview under the glaring fluorescent light of an interrogation room.

Melding the fragmentary lunacy (and trifurcated structure) of The Blackcoat’s Daughter with the fairy tale wickedness of Gretel & Hansel, the director embraces the darkness—which, it turns out, is where Longlegs claims his partner, “Mr. Downstairs,” dwells.

Perkins smartly implies more than he explains, and that’s doubly true of Cage’s performance as the title character, whose face is hidden from view for the film’s first half and resembles an apparent mask that feels designed to conceal a truly unspeakable and unfathomable reality.

Whether shrilly singing a recognizable ditty, sitting silently in his grungy workshop lair, or praising his great master of deception, Longlegs is less a child of this Earth than a creature of malicious myth, and Cage strikes an ideally unhinged cord as the specter, whose motives and machinations remain frightfully difficult to decipher. Equally indebted to the work of Conrad Veidt, Bela Lugosi, and Ted Levine, and yet emblazoned with a delirium that’s wholly its own, it’s a terrifying tour de force.

Longlegs’ concluding revelations cast it as a story of maternal sacrifice and sin, and the fine line separating selflessness and monstrousness. It contends that to protect often means to destroy, and that even in the best of circumstances, doing either results in doom.