A single effective jolt scare may be the byproduct of luck, but multiple successful shock tactics are evidence of genuine talent. Such is the case with Oddity, which hits theaters July 19, a thriller that proves so adept at rattling the nerves that its quiet moments are almost unbearably tense. Writer/director Damian Mc Carthy demonstrates an impressive ability to keep viewers on their toes, conjuring a mood of oppressive menace that more than compensates for any minor narrative shortcomings. It’s a feature debut that portends big things for the up-and-coming filmmaker.

In rural County Cork, Ireland, Dani (Carolyn Bracken) is restoring an old castle (with a square courtyard in its center) into a home for herself and her husband Ted (Gwilym Lee), who works as a doctor at a nearby facility for criminally insane convicts. This abode is more or less the last place in which any sane person would want to spend time, and that impression is exacerbated by the fact that, during this renovation period, Dani is sleeping in a lantern-lit tent on the floor of the unfinished main entrance area. Compounding the generally creepy mood, cell service is weak, although Dani does manage to reach Ted, who agrees to her request to invite her sister Darcy to dinner the following evening.

Once off the phone, Dani plans to drive into town for a meal. That trip never materializes because, after leaving Darcy a voicemail (“We are connected”), she goes to her car and hears a strange noise. Retreating inside, Dani becomes convinced that someone is on the other side of her locked door. When she opens the sliding peephole, she’s greeted by a bearded man with two different colored eyes who warns her that, while she was at her vehicle, someone snuck into the house behind her. “They’re in there now!” he pleads.

This sounds like a ploy to make Dani grant him entry, and yet faint sounds from a distant interior location give her pause, as does this stranger’s willingness to have her call the police. The question of what Dani should do hangs in the air, and Mc Carthy leaves it suspended, cutting sharply to the film’s title card and then to a hospital ward where a man discovers a fellow patient murdered in his room, his head smashed to pieces so that all that remains is a single glass eye.

Oddity

Colm Hogan/IFC Films/ShudderIn the nearby town, Ted visits an antiques shop run by Darcy (also Bracken), who turns out to be the blind, white-haired twin of Dani, who’s been dead for almost a year. Darcy explains to Ted that, despite her sightlessness, shoplifting isn’t a problem because everything in the establishment—which she inherited from her mother—is cursed, and most items have a way of finding their way back to her. Ted is a man of “science and logic,” and he humors his former sister-in-law as she tells him a story about her latest acquisition: a haunted bell that conjures the spirit of a dead bellboy.

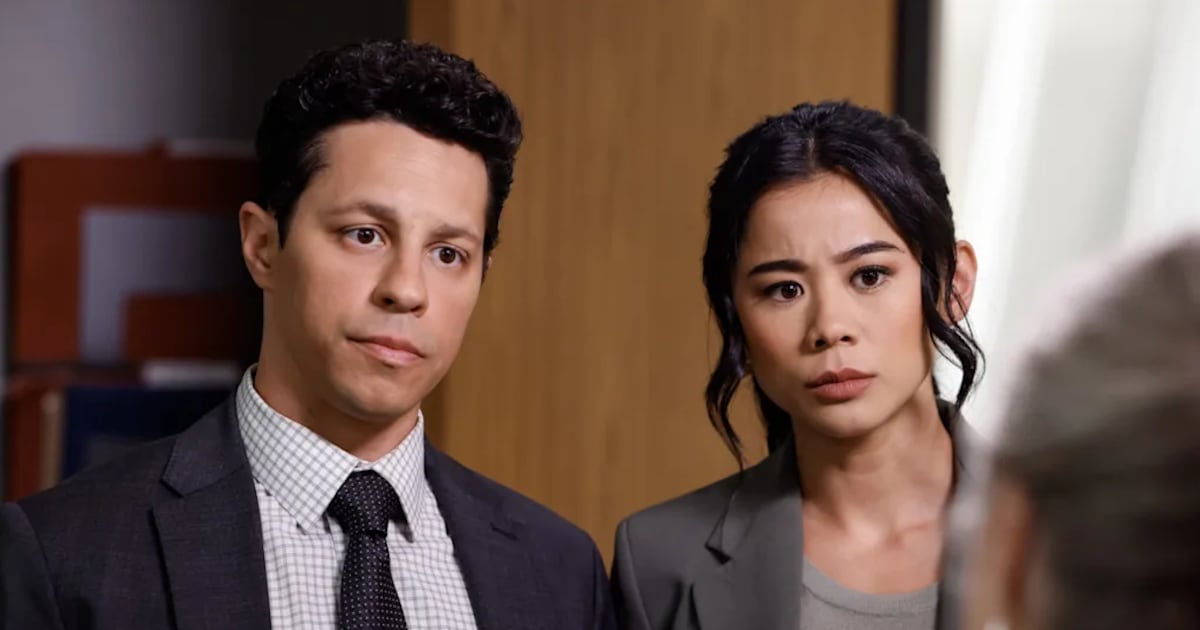

Because he knows that Darcy is a practitioner of the occult who fancies herself a psychic, Ted has brought her a fitting gift: the aforementioned fake eye, which belonged to Olin Boole (Tadhg Murphy), the mystery man who visited Dani on that fateful evening, and who was later convicted of her murder. Darcy wants to use it to see what went through his mind before he perished. Ted, not believing any of this, simply invites her to his home—which he now shares with new girlfriend Yana (Caroline Menton)—and bolts.

Even so, Ted and Yana are surprised when, on the anniversary of Dani’s death, Darcy appears, ready to take Ted up on his offer. Ahead of her arrival, Darcy has shipped a large crate (with a giant padlock) that contains a human-sized wooden mannequin with blank eyes, lined skin, a gaping maw for a mouth, and five holes in the back of its skull, out of which Yana eventually removes various ritualistic knickknacks.

Oddity

Colm Hogan/IFC Films/ShudderIt’s not long before this inanimate figure is sitting at their kitchen table, and shifting positions, in a thoroughly unnatural manner, and its presence is central to the film’s unnerving tone. Resembling an unholy demon that crawled out of the pits of Hell, the dummy is a watchful specter, if not the only malevolent force in Oddity, since the visions Darcy receives from touching Olin’s eye include the image of an even more terrifying madman in a white porcelain mask.

This fiend is the catalyst for one of the most startling jump scares in recent memory, and he looms large over the entirety of Oddity, which utilizes consuming darkness and patient rhythms to keep things ominous. Given that it boasts merely a few main characters (some of whom aren’t introduced until after the midway point), it’s not impossible to guess the identity of Dani’s killer, and a couple of climactic twists are a tad too convenient for their own good. Still, Mc Carthy’s plotting is by and large assured, highlighted by a canny (and fatal) trick played by one person on another which suggests a Machiavellian mind hiding behind a placid façade. Moreover, the writer/director has another sterling jolt in store for audiences—the result of slyly using repetition to create false expectations.

Oddity

Colm Hogan/IFC Films/ShudderWhile Darcy’s wooden buddy isn’t destined to just sit around, the material’s horror doesn’t solely hinge on the lifeless (or is he?) creature; rather, it builds eerie momentum from its opening passages so that when things finally turn monstrous, it feels less like a preordained payoff than the culmination of a slowly dawning nightmare.

Mc Carthy doesn’t skimp on the unsettling, whether it’s the sight of mutilated corpses or a close-up of a man biting another individual’s extremities. Nonetheless, his maiden directorial effort prioritizes unreal atmosphere and, in particular, the unseen forces that bind us to others—whether they’re living, dead, or something else entirely. It may exist in a familiar macabre universe of ghostly faces, puppet masters, menacing pawns, and vengeful spirits intent on punishing those who did them wrong, but what makes Oddity so pleasurably peculiar is its excellent use of those conventions for heart-stopping frights.