The last time the director Paul Schrader filmed Richard Gere’s body, it was a picture of virility. As Julian in 1980’s American Gigolo, Gere is an example of the ideal male form, whether in his Armani suits or undressed. He’s a man who works out hanging upside down.

Now Gere and Schrader have reunited for Oh, Canada, which premiered at the Cannes Film Festival, and the image of the star is very different. Playing a man on the verge of death, Gere (intentionally) looks terrible, his face drained and full of stubble. We hear how his body is failing him, about the cancer eating away at his insides, and the dried feces in his ass.

Oh, Canada can be a clunky film at times—with some awkward performances and labored dialogue—but it’s also an often fascinating match of director and actor, in which both seem to be trying to exorcize the demons of aging through art.

Based on the novel by Russell Banks, Oh, Canada centers on Leonard Fife, played as an older man by Gere and as a younger one by tall heartthrob Jacob Elordi. Leonard has spent his life being revered as a documentarian who fled the U.S. to avoid the draft, a move that his followers have deemed heroic.

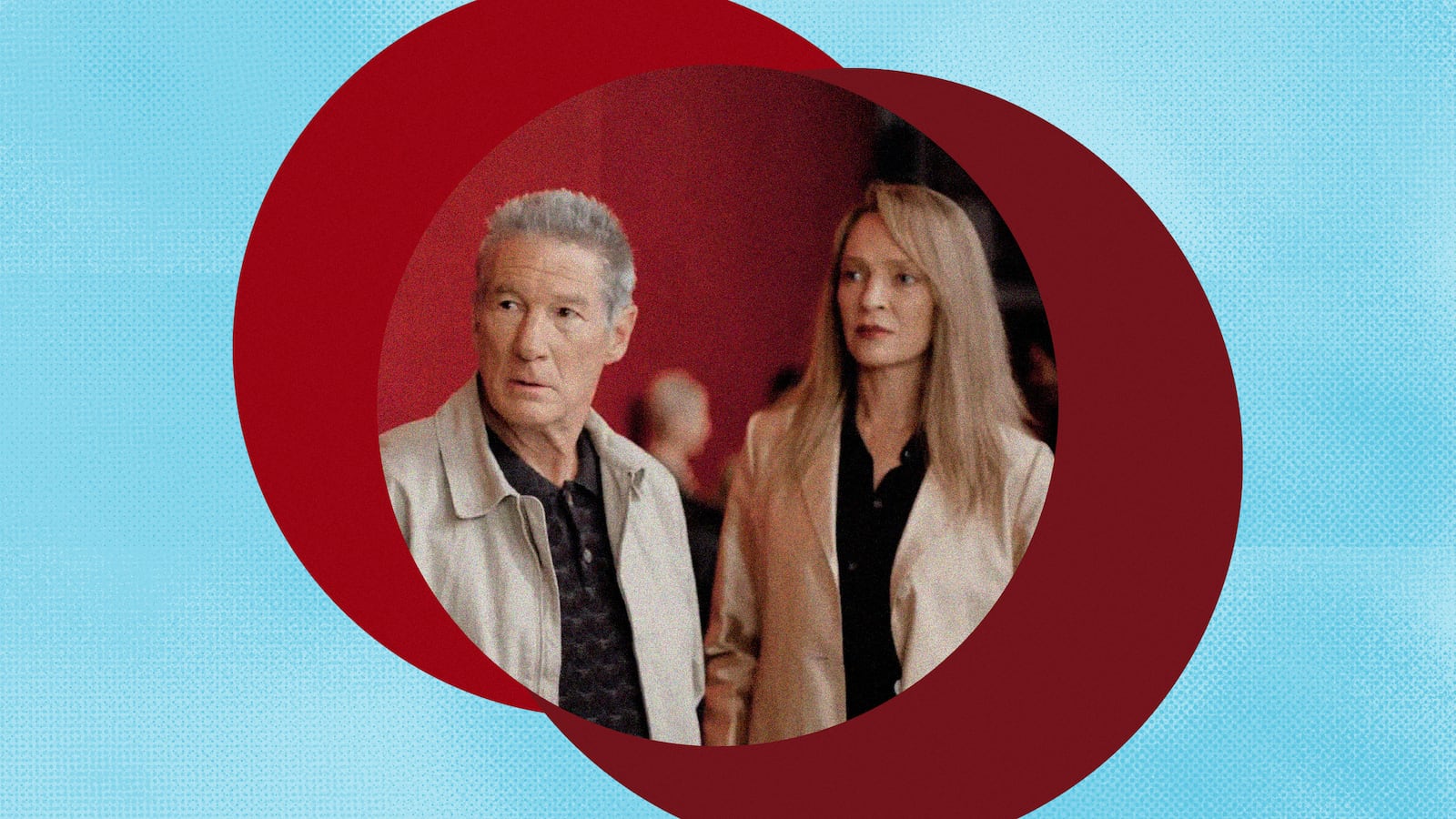

As the film opens we see a documentary crew, led by Leonard’s former students (Michael Imperioli and Victoria Hill), setting up in Leonard’s stately Montreal mansion. He has agreed to sit for one last interview. The filmmakers assume this will be a proud moment for Leonard—and for themselves as his acolytes—a tour of his accomplishments. He sees it as a chance to confess, specifically to his wife Emma (Uma Thurman), who was also a former student, which immediately signals the way he views women in his life.

Uma Thurman in Oh, Canada.

Oh Canada LLCThe narrative flits back and forth between the sickly Leonard’s telling of events and the illustration of those moments, in which Elordi steps in. The narrative the elder Leonard weaves is rendered in color, but memories within memories are in black and white. Occasionally, Gere himself, out of the old age makeup, stands in for Elordi or watches him act out these scenes. This can lead to extremely uncomfortable moments, like the 74-year-old Gere sidling up to the 20-something Kristine Froseth as Leonard's pregnant wife in 1968. Other moments are narrated by Leonard's son, Cornel (Zach Shaffer), as a postmortem after Leonard's death.

If this sounds confusing and perhaps muddled—it is, sometimes intentionally so. The story Leonard is telling is not linear. It’s the work of a mind addled by time and his medications. Emma pleads that what he is saying—about his multiple prior marriages and dalliances with women—is not true, and it’s hard to know what to believe. Is this his imagination? Or his last word?

Regardless of what is the actual fact, Leonard’s life, as he tells it, is marked by near constant betrayal of everyone around him. He cheats, he lies, and he leaves. In Leonard’s mind, he is a piece of dirt, and he wants to unburden himself of his personal crimes before he goes. His journey to Canada was not one of heroic defiance but one of avoidance.

The trouble is as Leonard rambles so does the movie. Elordi, who has proved himself an intriguing screen presence in Elvis and Saltburn, is hamstrung by playing this cipher of a man existing in a potentially fictional past. Thurman, meanwhile, is the weakest link in the cast, not entirely through her own fault. Emma’s devotion to Leonard remains under-developed, which in turn makes the desperation of Thurman’s line readings seem particularly forced. (She is also wrangled into a truly unfortunate wig in one sequence.) Gere, however, is captivating, especially when he's playing Leonard at his most ailing, frustrated at his inability to get across what he so desires. He cuts a decrepit figure and it’s hard to look away.

Schrader has spent his career telling stories of men who do bad things—from Taxi Driver to last year’s The Master Gardener, the third in a spiritual trilogy that included First Reformer and The Card Counter. Unlike those most recent efforts, there is no hope for salvation for Leonard Fife. He is embittered until the end, hanging on to his sins. Schrader’s protagonists usually write their innermost thoughts in composition books almost as a form of prayer. (One of his greatest inspirations is Robert Bresson’s film Diary of a Country Priest.) Leonard doesn’t have that outlet. He can only speak honestly if he’s in front of a camera. Or at least that’s what he says.

As a person who has spent most of his life engineering scenes for film, it is telling that Schrader gives Leonard this trait, and similarly significant that it is being embodied by an actor with whom he has such a storied relationship. In its depiction of a man trying to bare his soul, Oh, Canada feels like an offering to the audience and an act of self-laceration. I don’t think Schrader is saying that he is a fraud, but like the Calvinist he was raised as, he’s letting his guilt reverberate through his characters.

This doesn’t always make for satisfying viewing. Oh, Canada is unwieldy and sometimes hamfisted, including a closing music cue that will have you rolling your eyes. (I bet you can guess what it is.) And yet it’s hard to look away from how Schrader has taken his most beautiful troubled hero in Gere and forced him to wither away. Aging is a nasty business.