The only thing more unnecessary than remaking a great film is redoing a decidedly unique one. Such is the case with director Doug Liman and star Jake Gyllenhaal’s Road House, a modernized version of 1989’s Patrick Swayze-headlined cult classic, whose every fiber is so weirdly, extravagantly and inimitably ’80s that removing it from its time period is to court disaster. When this second iteration was first announced, it seemed like an endeavor doomed to fail if for no other reason than recapturing the original’s lightning-in-a-bottle style and spirit was impossible, and trying to replicate it with 2024 attitude was almost as futile. Now that the finished product has arrived, that prediction has come true, even if Liman’s latest does—at least in its final passages—tap into a gonzo vein that suggests the better movie this might have been.

Written by Anthony Bagarozzi and Charles Mondry with a surprising shortage of eclectic verve, Road House, which hit Prime Video on March 21, is the type of leaden affair that spells out its predecessor’s subtext and resorts to lame role-reversals and dull additions while doing away with most of its wackadoo elements. In a nowhere New York bar where men throw punches for cash, a tattooed fighter dispenses an adversary, and the fact that this roughneck individual is played by Post Malone turns out to be a hilariously incongruous bit of casting. Still, despite his camera swinging and swaying in tune with his subjects (and occasionally assuming the POV of his pugilists), Liman mainly opts for a dispiriting tone of gritty, grungy realism. When Dalton (Gyllenhaal) shows up and Post Malone’s tough guy balks at standing toe-to-toe with him, the protagonist’s imposing reputation is immediately established, as is his stoutness when, in the parking lot, he takes a stabbing (courtesy of a disgruntled better) in stride.

Tending to that wound, Dalton is approached by Frankie (Jessica Williams) with a proposition that she initially intended for another fighter: She’ll pay him $5,000/week to clean up her dive bar in Key West. Dalton declines, but, following a brush with death, he changes his mind and heads to the Sunshine State, where he discovers that Frankie’s roadhouse is called “The Road House.” A later joke about this name does little to offset its lack of originality, which is further heightened by Dalton’s discussion at a local bookstore with precocious young Charlie (Hannah Lanier), who remarks that Dalton’s tale—i.e., a stranger is hired to defend a small-town outpost from wealthy scoundrels—sounds “like a Western.” That Bagarozzi and Mondry’s script feels compelled to say what director Rowdy Herrington and Swayze’s Road House wordlessly suggested is one of many contrasts that do this film few favors.

Replicating its ancestor, Road House’s central location features musicians playing behind a mesh cage, a quirky female employee who brings Dalton breakfast after his first night on the job, and some underlings who improve their bouncer skills under Dalton’s tutelage. In these and other regards, Liman duplicates wanly, his derivativeness drained of any life. Moreover, he stages his initial introductions and action with moderate robustness but little hilarity, save for the sight of Dalton literally slapping around a group of biker-gang thugs causing trouble at Frankie’s establishment. Gyllenhaal speaks amusingly softly as he dispatches his foes with extreme prejudice, and to his credit, the actor’s exhausted and sarcastic retorts and wry facial expressions prevent his Dalton from being a totally faded photocopy.

Road House’s big alteration is that whereas Swayze’s Dalton was a suave, mulleted, martial arts-employing, tai chi-loving Zen desperado romance-novel hunk who was “the best” at his bouncer trade, Gyllenhaal’s hero is a disgraced and disheveled hoodie-wearing hobo who used to be a UFC heavyweight (i.e., he’s the worst). As before, Dalton is haunted by a past that involves killing a man. Yet here, that simply means he’s a psycho iteration of the Incredible Hulk whose sole fear is losing control of his rage—an overtly articulated point that simplifies what was implied by the prior film. After getting injured in a scuffle, Dalton visits a hospital where, per tradition, he meets a nurse, Ellie (Daniela Melchior), who patches him up and falls for him, presumably because he states things like, “No one ever wins a fight.” Their chemistry, however, is zero, because Liman spends virtually no time trying to develop it, just as he expends minimal effort fleshing out his peripheral characters, including Frankie and Charlie.

Dalton eventually learns that the root of The Road House’s problem is Ben Brandt (Billy Magnussen), the son of an imprisoned drug runner who wants Frankie’s bar for his own mysterious reasons. Magnussen does a passable job exuding wannabe-kingpin entitlement, but Road House mainly strives to generate electricity via real-life UFC icon Conor McGregor, who struts about and smashes everything in sight as a henchman named Knox who’s hired by Ben’s dad to finish the job his kid started. McGregor is a formidable presence and his prolonged battles with Gyllenhaal are the proceedings’ highlights. Nonetheless, even with a perpetually mad grin on his face, he’s no crazier than the first Road House’s gay-baiting right-hand-madman Jimmy (Marshall Teague), and the longer he’s on-screen, the more his wild-card energy proves repetitive.

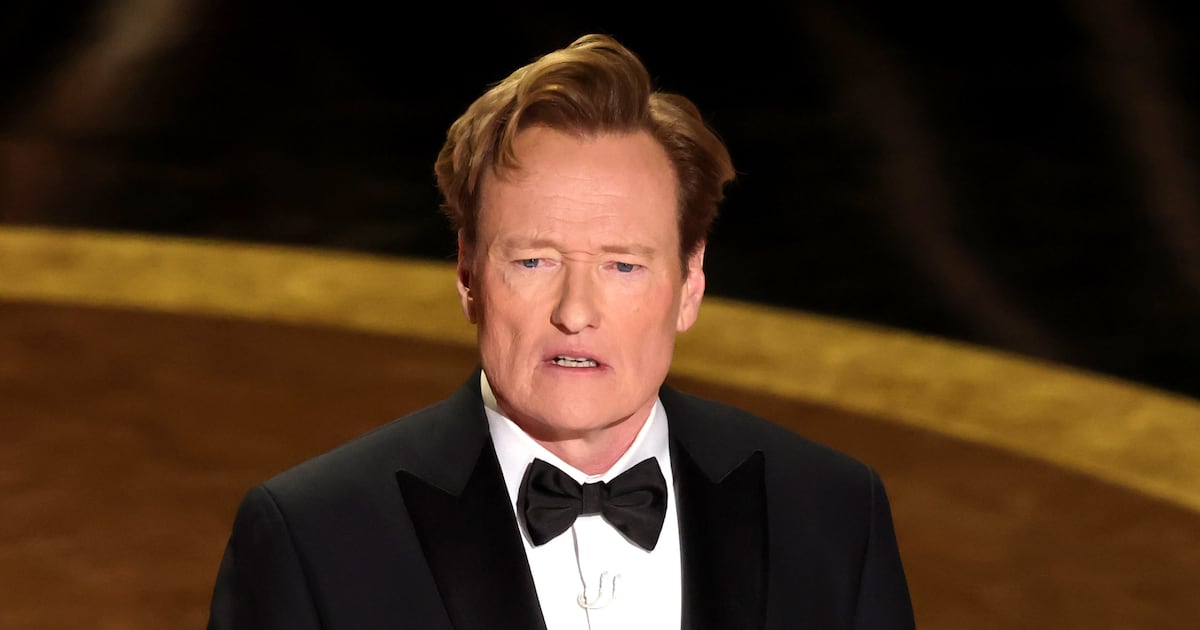

Jake Gyllenhaal

Amazon Prime VideoIn virtually every respect, Road House is a downgrade: Melchior is a bland nothing compared to the alluring Kelly Lynch (and her big hair and bigger glasses); Magnussen is a sniveling dweeb who can’t hold a candle to Ben Gazzara’s criminal bigwig; the acts playing at the Road House are no The Jeff Healey Band; and there isn’t even a counterpart for Sam Elliott’s intensely macho mentor figure Wade Garrett. Where are the locals who are cowed by the underworld enterprise that’s taken over their community, and ultimately learn to fight back? Where is the lovemaking against a brick farmhouse wall? And where is a climactic location as hilariously strange as Gazzara’s taxidermy trophy room? The director at least gets in a gratuitous butt shot, yet he mainly eschews truly bizarre touches.

Conor McGregor

Amazon Prime VideoOnly as it nears its conclusion does Liman’s film flirt with the sort of over-the-top absurdity its premise warrants, be it Gyllenhaal committing homicide with brazen impunity, getting tossed through the air between racing speedboats, or felling McGregor’s baddie in insanely violent fashion. When Knox remarks that the duo, squaring off on a tiny inflatable boat, now have their own private octagon, and Dalton replies, “What? Who taught you shapes?”, Road House partakes in the quippy lunacy that it needed from the start. Unfortunately, it’s too little, too late for a venture that largely retreads with minimal peculiarity.

Swayze’s Road House remains an enduring genre favorite precisely because it embraces the 1980s’ gung-ho excesses (Clothes! Hair! Women! Sexism! Brutality! Brooding!) with unabashed, unironic love and pride. Meanwhile, like the limp rendition of Metallica’s “Enter Sandman” that plays during its final fight, Liman’s adaptation is an uninspired cover song in desperate need of its forerunner’s fire and flair.