The Knick is one of the great television triumphs of the past decade, so word that its showrunners Jack Amiel and Michael Begler were taking over Perry Mason was exciting—especially in light of that HBO series’ severely underwhelming first season. Alas, different stewardship can’t right this reboot’s wayward course, as its second go-round, which premieres Mar. 6, is as pedestrian and lackluster as its first. “At some point, Mr. Mason, you must find all of your righteousness just a bit exhausting,” says a judge to the title character. He doesn’t, but viewers likely will.

Perry Mason’s problems begin with the ill-fitting ways it’s chosen to reimagine its source material. While its hero (played with compelling sullenness by Matthew Rhys) continues to be a noble-at-heart 1930s crusader dedicated to unearthing the truth, upholding justice, and protecting the innocent—and despite pairing him with his right-hand compatriots Della Street (Juliet Rylance) and Paul Drake (Chris Chalk)—the show reconfigures just about every other aspect of author Erle Stanley Gardner’s work in pointless and unsatisfying fashion.

Of those alterations, the most egregious is the fact that it’s far less of a legal drama than a hardboiled detective story, with private eye-turned-defense attorney Perry spending infinitely more time and energy searching for clues than arguing in court.

As envisioned by Amiel and Begler, Perry is a downbeat WWI vet and quasi-deadbeat dad who drinks and fights as much as he elicits confessions from witnesses on the stand. Conceptualizing the iconic lawyer as an idealist who battles for his beliefs in a corrupt city, and against a rigged system, feels reasonably faithful to the Perry Mason template. Yet ultimately, the action’s noir-ish attitude and affectations don’t fit their source material; regardless of the qualified nature of the character’s season-one victory, Perry Mason couldn’t muster anything approaching authentic fatalism. No matter his glumness, and the messiness of his case’s resolution, Perry himself came out on top.

Six months after we last saw him, Perry has turned his practice with Della—who’s studying to be a lawyer and demands a seat at the table as Perry’s equal—into one that only handles civil clients. This shift is due to Perry’s lingering shame and remorse over his prior defense of Emily Dodson (Gayle Rankin), but it doesn’t last when a Mexican family appears on his doorstep asking him to help their relatives, Mateo (Peter Mendoza) and Rafael Gallardo (Fabrizio Guido), who have been arrested and charged with the murder of Brooks McCutcheon (Tommy Dewey), the reckless, enterprising wheeler-dealer son of local magnate Lydell McCutcheon (Paul Raci).

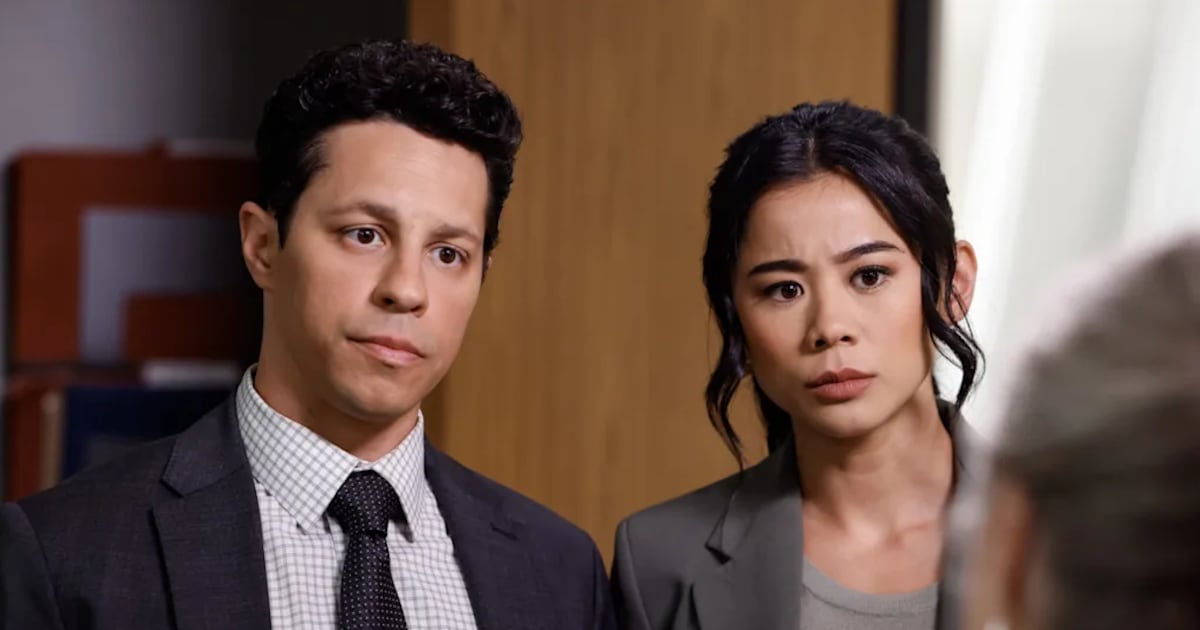

At the conclusion of a premiere episode that details Brooks’ kinky sexual proclivities, act of catastrophic sabotage aboard a gambling ship, and tensions with his father over his dreams of bringing a baseball team to Los Angeles, Brooks is shot dead in his car, and assistant district attorney Hamilton Burger (Justin Kirk) and his prosecutor Thomas Milligan (Mark O’Brien) are sure they have the culprits. Disillusioned Perry is initially happy to pass up this case, but it’s not long before he and Della—bolstered by news gleaned from former colleague-turned-DA-lackey Pete Strickland (Shea Whigham)—change their tune and accept the underdog assignment.

Ho-hum sleuthing follows, all as Perry Mason introduces a raft of characters who function as possible alternative suspects. Chief among them are Brooks’ dad Lydell, who was disgusted by his son’s immaturity and thoughtlessness; crooked LAPD detective Holcomb (Eric Lange), who was working with Brooks on his gambling boat; and oil barren Camilla Nygaard (Hope Davis), a polished and poised single bigwig who, at one of her gala events, winds up charming Della, even as the wannabe-lawyer enters into a clandestine lesbian affair with Anita St. Pierre (Jen Tullock)—a thread almost as superfluous and inert as Perry’s budding relationship with schoolteacher Ginny Aimes (Katherine Waterston).

Perry’s fraught bond with his son and Paul’s bitterness over being duped by Pete into screwing over a Black entrepreneur—which makes him rethink his allegiances—are additional decorative facets of Perry Mason, and somewhat necessary ones, considering that the season’s central mystery is a painfully easy one to unravel.

There’s no spark to this whodunit, irrespective of early bombshell revelations that cause Perry to question his commitment to Mateo and Rafael and to engage in laughably wrongheaded conduct. More frustrating than his foolish behavior (and attendant rationalizations), though, is the sheer dearth of energy to this entire endeavor, which shuffles along while striking a mournfully cynical pose—epitomized by the score’s incessant somber solo trumpet—that’s both affected and contradicted by its protagonist’s indefatigable (if world-weary) optimism.

Perry Mason plays noir dress-up without wholeheartedly embracing its bleakness, just as it uses the skeleton of Gardner’s books for yet another period piece retrofitted with decidedly modern viewpoints about race, sex, class, and society’s real villains. At the same time, it saddles everyone with so much guilt that the show repeatedly grinds to a halt in order to let Perry and company lament their mistakes and the (unintended) consequences of their actions. There’s no reason (or need) for a tale like this to be upbeat, but neither is there cause for such lethargy, and that extends to the show’s muted aesthetics, which have a low-lit, brown-gray drabness that’s only occasionally offset by a gem of a shadowy composition (usually featuring a solitary figure in silhouette).

Unlike Rylance and Chalk, who are functional at best, Rhys is magnetic enough to keep the series from sliding into complete torpor. He’s aided, intermittently, by Whigham, who exudes the sort of genuine ragamuffin despondence and moral ambiguity and conflict that the show desperately requires. Both, however, are powerless to consistently enliven a saga that’s narratively, psychologically and politically transparent. There’s too little here, all of it taking place too listlessly, to warrant one’s undivided attention, much less elicit enthusiastic anticipation.

Filled with numerous superficial details, subplots and talk about the possibility of true justice in a fundamentally unfair world populated by the criminal and compromised, Perry Mason pads itself to the point of distension on the way to a finale that most will have seen coming weeks earlier. It's difficult not to think that the original Perry Mason would have wrapped this mystery up in two hours, tops.

Sign up for our See Skip newsletter here to find out which new shows and movies are worth watching, and which aren’t.