Peter Dinklage isn’t one to repeat himself, and he’s proving that once again in Cyrano, a musical adaptation of Edmond Rostand’s classic 1897 play Cyrano de Bergerac. The new version boasts songs by The National and the actor in the title role as a crooning poet who expresses his love for fair Roxanne (Haley Bennett) by writing letters to her on behalf of soldier Christian (Kelvin Harrison Jr.). It is, on the one hand, a clear departure from Dinklage’s acclaimed performance as the scheming Tyrion on Game of Thrones. Yet it’s perhaps not as different as it might first appear, since both are underestimated men with cagey instincts and fundamentally romantic souls. Having originated the part (alongside Bennett) in a 2018 stage production that was conceived, written and directed by his wife Erica Schmidt, Dinklage is an ideal Cyrano, his lyrical yearning and misguided cunning serving as the engines that drive this tale toward tragedy. He’s the magnetic center of this swooning if melancholy affair, even without the elongated nose that has long been the character’s trademark.

Following an awards-qualifying run in late December, Cyrano is garnering awards attention for its headliner, a well-deserved accolade for an actor who’s elevated every work with which he’s been associated, be it Tom McCarthy’s The Station Agent, Jon Favreau’s Elf, Marvel’s Avengers: Infinity War, J Blakeson’s I Care A Lot, or—of course—HBO’s epic fantasy series, which earned him four Emmys, a Golden Globe and a Screen Actors Guild Award. In the wake of that global hit’s conclusion, Dinklage has been an exceedingly busy man, with numerous projects in the pipeline. His immediate focus, however, has been on this retelling of Cyrano de Bergerac, first as a play and now as a big-screen feature helmed by Joe Wright (Darkest Hour, Atonement). For the actor, it’s an opportunity to step out as a bona fide leading man, as well as to demonstrate his singing prowess—something he admits was a challenge.

With captivating panache befitting his protagonist, he delivers a turn that’s at once suave and insecure, dashing and timid, and in the process he gives the film the very beating heart it demands. In advance of its theatrical debut, we spoke with the candid Dinklage about his vocal prowess, his love of guerrilla-style artistry, and his feelings about the backlash to the Game of Thrones finale.

Was Cyrano—in both its incarnations—made possible, to some extent, by the success of Game of Thrones? And did you feel like now is the time to do something bold and different?

That’s a good question. Especially with something like Game of Thrones, I’m so happy to use any modicum of success from that show and carry it into putting the spotlight, if I need to, onto something that I enjoy and love being a part of. Happy to oblige. I think the way Cyrano came about didn’t really require my Game of Thrones credentials, because Erica Schmidt, our adapter and original theatrical director, was commissioned by a company, and I sort of hitched my pony to that wagon. I never really considered playing the role of Cyrano until I read Erica Schmidt’s adaptation and talked to her about her ideas for it. Then I was really hooked. But it was going to happen with or without me. I really just petitioned for the role, and that was in the stage development of it all. When Joe Wright, the director of the film version, came to see the stage version, he was inspired by what Erica had done to make the film, and I personally took a back seat. I mean, yeah, sure, people probably came to see the play because they wanted to see the guy from Game of Thrones, and that’s totally fine. But hopefully, what they walked away with is the experience of the whole piece. That’s separate.

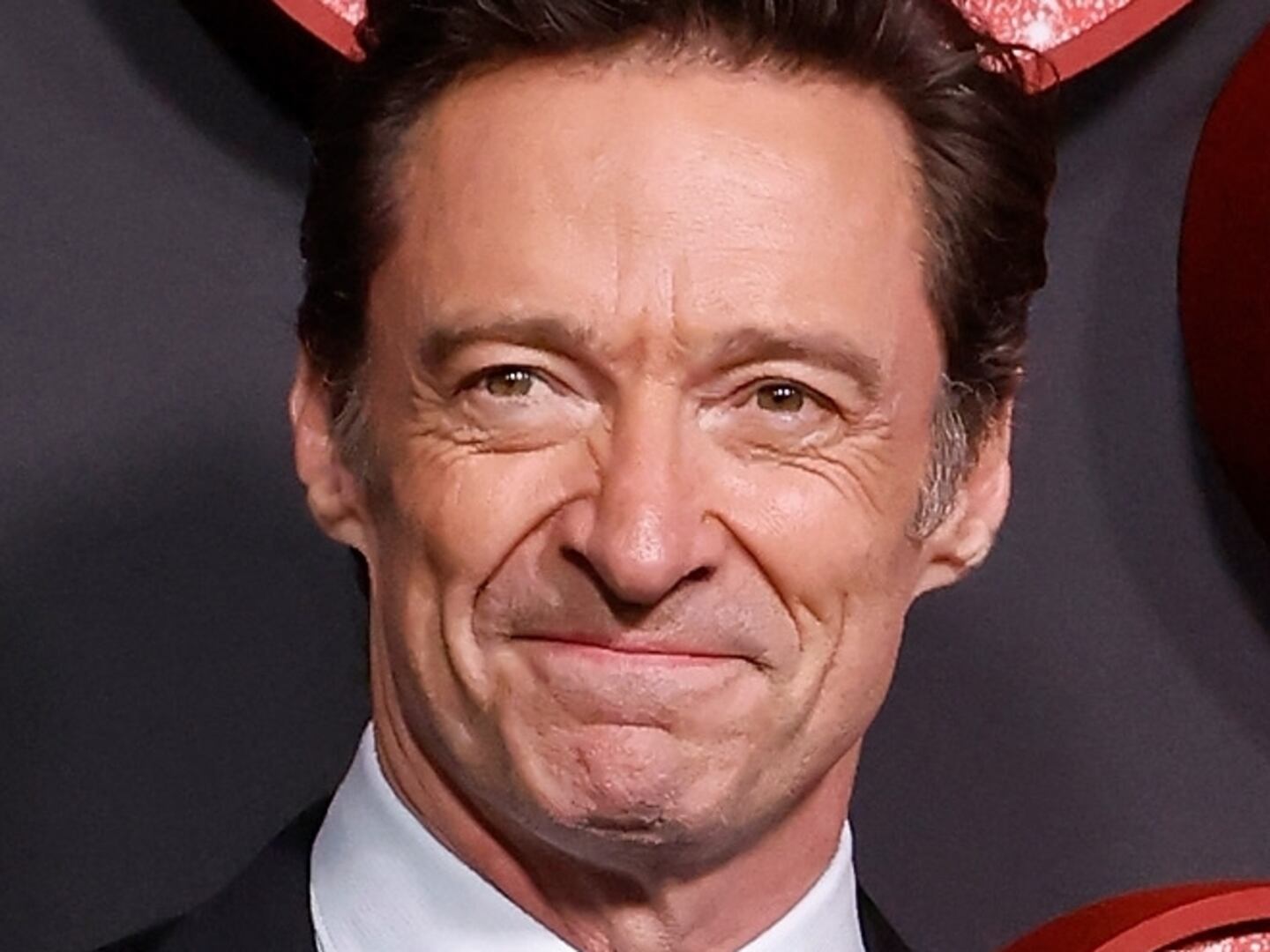

Haley Bennett as Roxanne and Peter Dinklage as Cyrano in Joe Wright’s Cyrano

Peter Mountain/MGMThe play debuted as Game of Thrones was ending, and there was a notably divisive reaction to the show’s conclusion. And as Cyrano is now premiering, there’s a lot of awards buzz building, around you in particular. In both instances, do those outside voices affect you in some way, or do you completely tune them out?

For me, it’s pretty easy, because all that stuff happens about a year after you’ve made the movie or you’ve wrapped on a TV show. We have the advantage of having some distance from it, especially as actors. By the time the reaction to Game of Thrones came out, I had done a movie, I’d started working on this production of the Cyrano stage adaptation, and between wrapping on Cyrano and talking to you now and what you’ve just referenced, it’s been a busy year. I’ve done four films this year, and Cyrano, which I’ve thrown myself fully into. Now that this Cyrano is coming up again, it’s lovely—it’s like looking through an old photo album of something you’re proud of. But yeah, I don’t digest any of that. It’s all fun.

I’ve got to say, the Game of Thrones backlash, for me, personally, people probably had issues with it. But I think they were just angry that we were ending. I think it was sort of like we were breaking up with the world, and they didn’t want to be broken up with yet. Because if you watch that show, from the beginning, that was the point of the whole show—how characters change. If you look at Jaime Lannister, for example, he pushes a kid out a window at the end of the first episode, and by the end of the show he’s like a hero in so many people’s minds. Did you forget that he pushed a kid out the window? Maybe, maybe not. That’s what I loved about that show—the complexity of character. And with Daenerys, she was viciously brought down, repeatedly, from the beginning, and something was going to happen. There’s corruption in the world. There are tyrants in the world. And those tyrants weren’t always tyrants. They were schooled and trained into being tyrants. That’s what I loved about our show. And so I say to our fans, it really shouldn’t have been that surprising.

Between you and me, I liked the way it ended.

Me too, Nick! Basically, wait until the show is over before you name your puppy after a character.

In Cyrano, you play a romantic lead—albeit a frustrated and imperfect one. Was that part of the appeal, given that those aren’t usually the parts you’ve tackled?

Tyrion was romantic, and I’ve done a number of roles that, even if they don’t run off into the sunset with the leading lady, I like to bring love and affection and romance to all the characters I play. I don’t think that’s always the case on the paper, but I like to bring a little dance-step of romance to everything I do. Because that’s how I see my way into characters—who they’re attracted to, and all of that, because that’s what leads a lot of us, as people.

Why have we been raised by Hollywood films where beautiful white people have cornered the market on romantic leads? I think we live in a much more complicated time right now. The world is so diverse, and everybody has a love story, and I want to know those love stories—not the love stories that we’re spoon-fed that just seem a repetition on a theme. I want to unearth. I want a love story that I’ve never seen before, with characters and people that I’ve never seen before. Unlikely lovers. Cyrano certainly is a variation on the love story. It’s a tragic love story, because he’s basically using another person, and is complicit, and has created this lie—he’s lying to the woman he loves. So, I don’t think Cyrano fully understands what love is, because if you love someone, love is the opposite of lying to them.

Have you always wanted to do a musical?

I definitely wasn’t looking to do a musical, because I never considered myself a singer. That’s not being humble, that’s just the truth, because that’s not what I do for a living. There are amazing singers out there who have inspired me. But I just wanted to try something new, challenge myself, scare myself, see if I could even do it—and if it failed, then okay, I’d be the first to walk away from it. There’s an old Beckett quote talking about how there are no mistakes, you’ve just got to fail, and fail better. It just sort of came about. Then, The National, for years, were one of my favorite bands; Matt Berninger in particular, his voice is just incredible. So when Erica Schmidt had the idea to make all the long monologues of love into love songs that they had written, that was what really hooked me, because they blended so beautifully with what Erica had written on the page.

I think of musicals as lavish chorus numbers, and West Side Story, and a skill set that I really don’t have. You go see a Broadway musical, and I just go, wow, that is something I could never do: singing and dancing and back-flipping, and you’re not out of breath while you’re singing this beautiful song? But this was very different. This seemed more like a play with songs. To me, it seems like a movie with songs, because the songs are very intimate and personal, and there are occasionally only one or two people singing at the same time. That was a version of the musical I could find my way into.

What was the biggest challenge in transforming the stage show into a film?

There’s a number of challenges, but that’s part of the thrill and the fun. They’re such different art forms, theater and film, and you have to embrace their differences. It’s the same thing with a film version of a book. You have to change and adapt and not do a carbon copy of the book. Because why not just read the book instead, if they’re so much alike? Cinema has its advantages and disadvantages; everything does. There’s nothing better for performers than a live audience, for example. It’s the same reason why bands go on tour. They record their albums in the studio, but the thrill of the live audience, and playing for them and getting that response and love, and having it change and alter for every single performance, with every single show you do—which it does for the stage; every performance is different, mostly based on the audience’s response—that’s a thrill. But with a film, you get to be much more intimate, especially with songs like this. Like, I didn’t have to sing out to the back row. I can sing much more quietly, because the camera is inches from my face. With a piece like this, I thought it was really nice to explore that side of it all.

Peter Dinklage as Tyrion Lannister on Game of Thrones

Helen Sloan/HBOGiven that you starred with her on the stage, was Haley Bennett’s participation key to you signing up for the film?

It all came about very serendipitously and out of the blue. Erica Schmidt hired Haley to play Roxanne and hired me to play Cyrano, and we did a workshop production up in Chester, Connecticut, and Haley at the time was partners with Joe [Wright], personally. So Joe came to the show to support his partner, and in doing so, he fell in love with what Erica had created, and was inspired to make the film version of it with Erica as writer, and myself and Haley as the leads. He basically wanted to take what she had created and make this cinematic version of it.

You spoke earlier about your musical skill set, and despite Cyrano being a musical, it doesn’t feature any traditional dance numbers. Were you disappointed you didn’t get to show off your moves?

Dancing? Oh no. The only people who are going to see me dancing are my kids. I just dance to make them laugh. No, that’s something I’d have to seriously take a look at [laughs]. Christopher Walken brings a dance to every one of his performances because he’s a brilliant dancer. I try to find out how I cannot dance.

As you said, you’ve been exceedingly busy of late. Do you have a guiding strategy for mapping out your career’s path?

I wish I had a guiding strategy. My only guiding strategy is to never repeat myself. Like, the last thing I want to do is make a musical about heartbreak right now. I just did a comedy heist film, and the last thing I want to do next is a comedy heist film. It’s just the art of not boring myself, or feeling repetitive.

You’re reportedly involved in a remake of one of my childhood favorites, The Toxic Avenger. Is that still happening?

Oh yeah, it’s done and dusted, man. It’s in post-production now. We shot it in Bulgaria this summer, and it was a thrill. Macon Blair, one of the most creative people working today—he wrote and directed it. I don’t know if you saw his film I Don't Feel at Home in This World Anymore…

Actually, it was one of my favorites from that year.

The combination of Toxic Avenger and Macon Blair, that was a no-brainer. I was there, wherever you need me. We had a lot of fun. It’s not necessarily a remake, but it’s his version of that story. And that’s just guerrilla filmmaking, man! Troma films, they just did it because they loved making movies. They had such enthusiasm, and it shows. They’re B-level films—of course they are—but it’s the joy behind the camera and what you see on film that just infuses those films. If B-level means brilliant-level, then for sure, man, those are great. It’s what I love to do: guerrilla-style filmmaking, anarchy, messy. Everything nowadays, with Hollywood movies, they’re so clean around the edges. There’s nothing wrong with roughing them up around the edges.