The influence of Pee-wee Herman—née Paul Reubens—can’t be understated. And in the wake of Reubens’ passing on Sunday night, at the age of 70, it’s an appropriate, if saddening, time to emphatically remind everyone of it. While Reubens’ and Pee-wee’s ubiquity waned following the character’s late-’80s and early-’90s heights, the impact that they left reverberates today in all matters of subversively sweet, cross-generational comedy.

Originating in the late-’70s as part of Reubens’ stand-up act, Pee-wee went on to become an offbeat late-night guest; leading man of an iconically strange, funny, endlessly quotable film; and, most importantly to me, the host of one of the most unique children’s shows ever made.

Premiering on CBS in 1987, Pee-wee’s Playhouse capitalized on the character’s childlike energy to make him enjoyable for children. The result was a colorful, boisterous, surreal, absurd, and completely delightful television show—one whose influence can still be felt in the many children’s shows and cartoons that followed in its footsteps.

It’s important to remember that Pee-wee was not intended to be a kid-friendly character. Despite his ambiguous age and asexual persona, he still played into Reubens’ more adult comic sensibilities; just watch Herman’s early Cheech and Chong appearance, repeat Letterman visits, and stage show, The Pee-wee Herman Show. Even Pee-wee’s Big Adventure, his breakout role, played as much to the adults in the room as the kids that watched along with them.

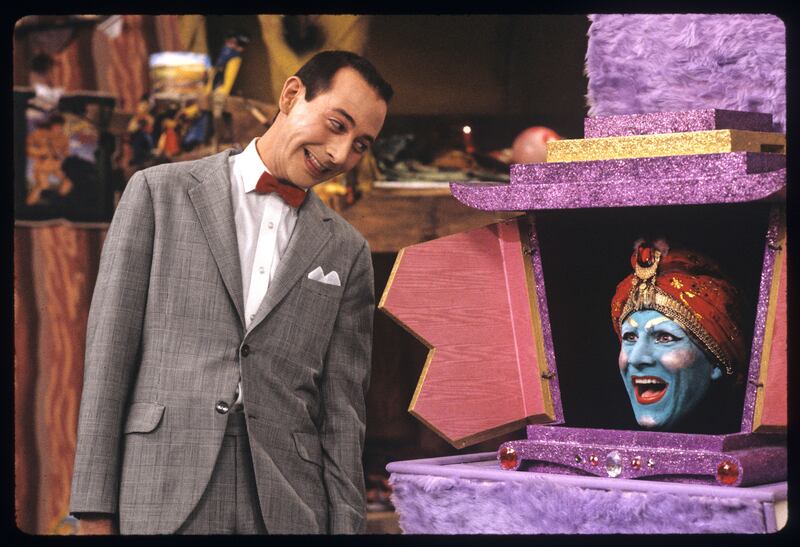

But following Big Adventure’s success, Playhouse gave Reubens a chance to develop and indulge in the character’s high-energy, cross-demographic appeal. Every aspect of the show was a marvel of character-building, the kind that kids find joyfully fun and adults find admirably creative. The show took place in Pee-wee’s house, which was full of sentient furniture, kitschy wallpaper, genies in cupboards, and a machine that spat out a “secret word” every day. (If someone unknowingly says the secret word, you better start yelling.)

Every element of Pee-wee’s house was a marvel of design—a veritable dream for a child with an overactive imagination. It looked as though a child had scribbled it on pieces of paper, using every crayon from the box: Pee-wee’s red door was shaped like a zig zag. He had a secret compartment designed in the shape of his beloved bike. There were lightbulbs the size of his head and smiley faces cut out into the walls. The coolest of all was his video phone, whose receiver was a can with a cord attached; it was in a phone booth shaped like an abstract face, replete with giant red lips.

And then there was his revolving door of wacky neighbors. A young Laurence Fishburne notably appeared as Pee-wee’s very cool friend Cowboy Curtis, sporting a Jheri curl as a modern-twist on his Wild West archetype. Phil Hartman of rising Saturday Night Live fame played Captain Carl, whose patience for Pee-wee was limited. Miss Yvonne (Lynne Marie Stewart), who sported an over-the-top wig and garish makeup, had the hots for all the guys. There was a lifeguard, a man who introduced the random cartoon that appeared in each episode, and Reba the Mail Lady (S. Epatha Merkerson), who offered a tenuous connection to the real world, entering the house to find every little part of it confusing—a self-aware nod to Pee-wee’s weirdness for the parents in the room. Sandra Bernhard appeared on the show too, as did a young Natasha Lyonne. And in the show’s Christmas special, guests included Magic Johnson, Joan Rivers, Oprah Winfrey, Cher, Whoopi Goldberg, Grace Jones, and more.

While my parents could appreciate all the fun cameos and human characters, I loved the various puppets, like Chairy, Mr. Window, Pteri, Conky, Clockey, and Globey, whose names are self-explanatory. That these were Pee-wee’s real best friends, and that they all lived in this house together was the stuff of my childhood playroom games come to life. I couldn’t articulate it then, but I was watching the manifestation of my dreams: talking objects; a disregard for rules of logic, physics, or human behavior; and exuberant color in every corner. Guided by a silly-voiced oddball like Pee-wee, watching Pee-wee’s Playhouse was like taking a class called “Intro to the Avant-Garde.”

What made it especially cool was that it was an inspired work that most kids’ programming lacks. Playhouse did not moralize or pander to children, instead focusing on how to be a decent human. The message of Pee-wee’s Playhouse was that you should embrace your deepest, weirdest, most surreal thoughts, while still treating others with respect and kindness—much as Pee-wee, for all his weird voices and spontaneous yelling, did. That a mainstream network aired this every week for children (and their parents, who could appreciate the familiar faces, non-pedantic humor, and occasional innuendos) was especially meaningful.

Its prominence also opened the doors for more creative kids television to come, following in Playhouse’s footsteps. CBS reportedly invested heavily in the show, allowing for its high-quality production design and usage of mixed media. In some cases, Playhouse even paved the way for shows in a similarly idiosyncratic mold directly. Craig Bartlett, who went on to create similarly stylish Hey Arnold!, was one of the show’s creative designers; Arnold appeared in Playhouse’s claymation “Penny” shorts, directed by Bartlett. Working alongside Bartlett and the other artists was Wallace and Gromit co-creator Nick Park, whose innocently subversive cartoons feel indebted to Playhouse.

The show also used one of the more famous stock music tracks known to children: “Tomfoolery,” an instantly recognizable song to anyone who watches SpongeBob SquarePants. SpongeBob creator Stephen Hillenburg later cited Pee-wee as one of the biggest influences on the cartoon. Mark Mothersbaugh of Devo, meanwhile, wrote Playhouse’s score, which paved the way for a wildly successful career in children’s television. If you were too young for “Whip It,” you were definitely old enough for his other most famous creation: the theme song for Rugrats. Another fun fact: Playhouse’s theme song, composed by Mothersbaugh and Reubens, was performed by Cyndi Lauper.)

But most of all, it instilled in a generation of kids like me, who was born a few years after the show ended but watched it religiously on video tapes, a love for the unfettered creative spirit. Its intoxicating silliness played a large part in many budding senses of humor, giving us a love for jokes as predicated on visual expansiveness as on the words themselves. We came to love irony as much as we did sincerity, for Playhouse trafficked perfectly in both. When Adult Swim licensed Playhouse for reruns in 2006, it actually made sense: The network clearly took inspiration from Pee-wee’s out-there, colorful, charming, completely original spirit. If there’s any brand that built a reputation on all the creative tenets of Pee-wee’s Playhouse, Adult Swim is it. (Also, both Pee-wee’s Playhouse and Adult Swim are very popular with stoners.)

Reubens did so much more than just be Pee-wee Herman, of course. But his most indelible mark is the one he left as this unmatched character, and Pee-wee’s Playhouse is arguably the greatest distillation of both Reubens’ comedic ethos and the potential of kids’ TV. Playhouse’s cancellation in 1990 was already a great loss; the death of Reubens is another, even greater one.

Keep obsessing! Sign up for the Daily Beast’s Obsessed newsletter and follow us on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and TikTok.