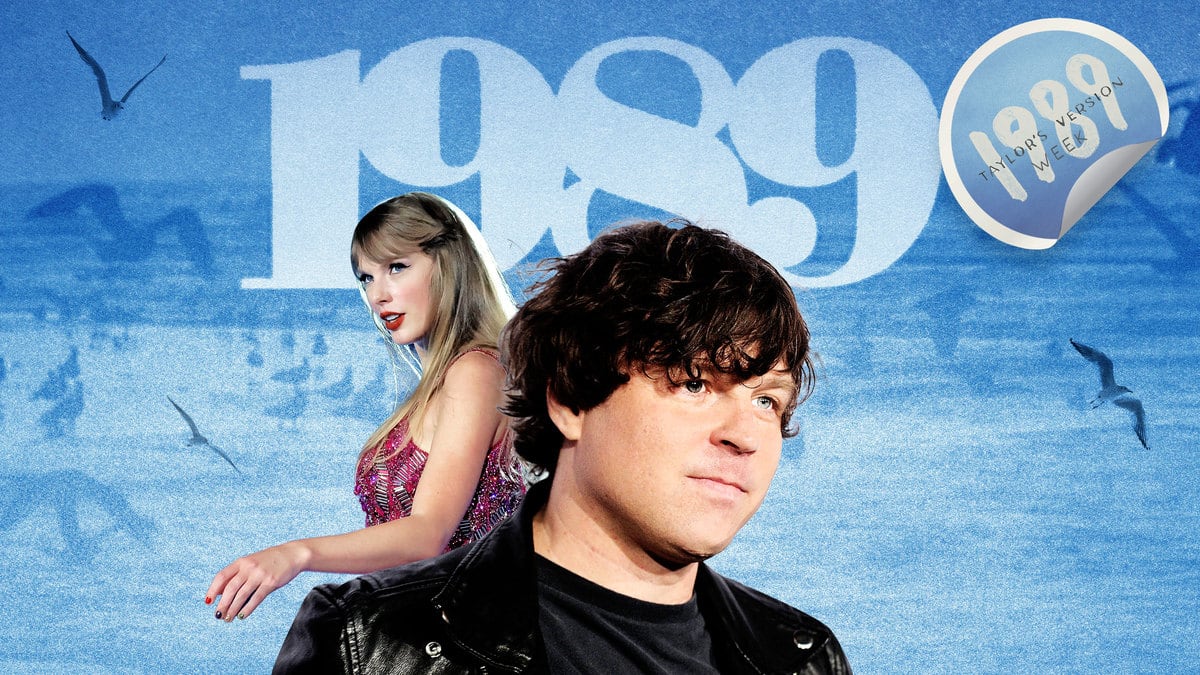

Remember When Ryan Adams Covered Taylor Swift’s ‘1989’? Ew.

1989 (TAYLOR’S VERSION) WEEK

“Serious” music critics didn’t even bother covering Swift’s blockbuster album at the time. Instead, they celebrated this ridiculous reinterpretation.

Trending Now