From Gravity and Interstellar to The Martian, Ad Astra, and High Life, the sad-astronaut sci-fi movie has lately become a subgenre unto itself, and Johan Renck’s Spaceman now joins its weepy ranks. A tediously maudlin saga about a Czech cosmonaut on a mission to the far reaches of the galaxy who really misses his wife and can’t get over his dad’s mistakes—and finds a way to cope with both courtesy of an unexpected new alien pal—it’s a star vehicle for Adam Sandler that strives for stratospheric emotional heights and yet proves so self-seriously somber and saccharine that it plays like a leaden parody.

Jakub (Sandler) moves about his spaceship with sunken cheeks, exhausted body language and a haggard look in his eyes. This is nominally due to the fact that his toilet won’t stop making horrible noises that are keeping him up at night and slowly driving him insane. Mostly, though, it’s because he’s sad. In case this wasn’t immediately obvious, Chernobyl director Renck’s film (on Netflix March 1), adapted from Jaroslav Kalfař’s book, has Jakub make a PR phone call down to Earth, during which a young sixth-grader tells him that she read that he’s “the loneliest man in the world.” Jakub denies this but he’s unconvincing, and his spirits aren’t lifted by the notion that he’s on the cusp of saving the universe from a big purple mass of particles on the outskirts of Jupiter dubbed the Chopra Cloud that he’s been sent to investigate, all by himself, on a year-long solo mission.

Five-hundred million kilometers from home, Jakub’s only real contact is with Peter (The Big Bang Theory’s Kunal Nayyar), his mission control buddy, whose job it is to keep Jakub in good mental and physical shape. Alas, that’s difficult because Jakub is so sad, and the present cause of his sadness is his inability to use his video phone to reach his wife Lenka (Carey Mulligan). Peter makes excuses about why Jakub can’t connect with his spouse but Spaceman makes clear that it’s because Lenka, who is pregnant, is also sad, and her sadness has to do with her husband. Having once again been abandoned by Jakub, Lenka is akin to the loneliest woman in the world, and as her cosmonaut baby daddy approaches Chopra Cloud, she sends him a recorded message notifying him that she’s ending their marriage. Yet unfortunately for her, Jakub’s boss (Isabella Rossellini) blocks that transmission from getting to the cosmonaut because she recognizes that he’s already sad enough and making him sadder still will simply further jeopardize their venture.

Spaceman exists in an alternate reality in which the space race is led by the Czech Republic and South Korea (whose emissaries are hot on Jakub’s tail), and its scant contextual details are mostly puzzling, such as Lenka’s eventual relocation to a rural convent for single mothers. Instead, the primary emphasis is on Jakub’s visage, which segues from forlorn to scared when, one morning, he awakens to discover that his ship has a surprise second inhabitant: a giant extraterrestrial spider that speaks in the calmly curious and wise voice of Paul Dano. Beset by nightmares about his father as well as wistful dreams about Lenka, Jakub assumes that this creature is an additional figment of his imagination, especially since it doesn’t register on any of Peter’s sensors. However, once he gets over his initial alarm (exacerbated by a recent reverie about a spider crawling under his skin), Jakub slowly befriends the beast, and even gives him a name: Hanus.

Adam Sandler

NetflixWhile Hanus doesn’t reveal how he boarded Jakub’s vessel, he does explain why he’s there: “Your loneliness intrigued me.” This makes Hanus the cosmonaut’s de facto marriage counselor, there to plumb the depths of his malaise, and Spaceman soon has the creature invading Jakub’s mind, forcing him to revisit his memories about his dad and his wife, all of them shot with a fish-eye-lensed smeariness that’s as affected as the material’s overarching air of solemnity—here exacerbated by director Renck’s decision to shroud virtually everything on the ground and in the stars in murky darkness. What they reveal is that, despite loving Lenka, Jakub has a habit of constantly leaving her for space, and that he thinks becoming a global hero will somehow absolve him of his father’s prior communist-treachery sins. “You go where I go, and I go where you go,” says Lenka in recurring flashbacks, and the fact that Jakub has reneged on this deal is central to his (and her) discontent.

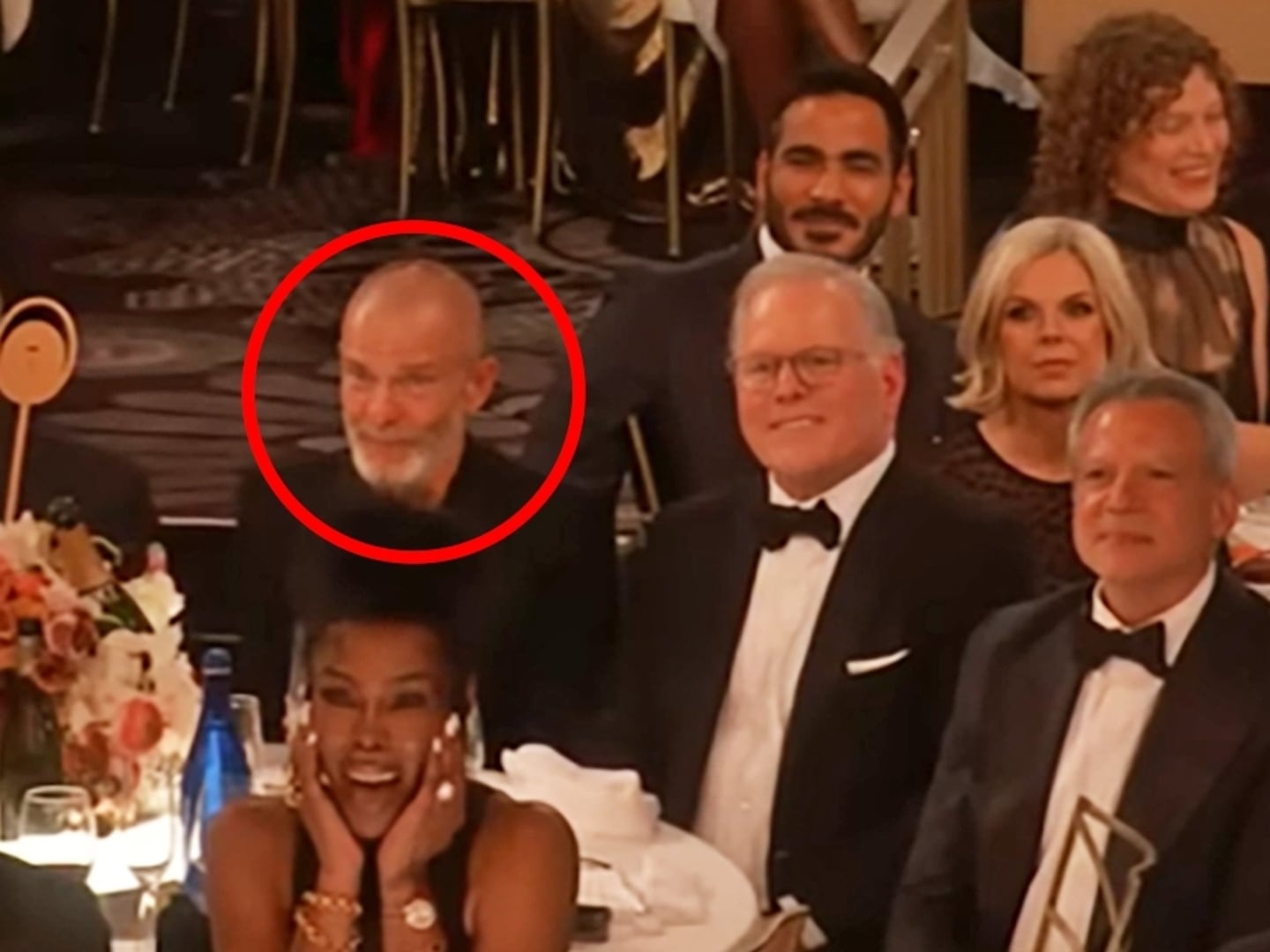

Hanus (voiced by Paul Dano)

NetflixInterpreting Jakub’s condition isn’t tricky because Spaceman both wears its heart on its sleeve and says precisely what it’s thinking, the latter to the point of exasperation. “If I only saw her like I saw her then,” Jakub laments. “If I had known then what I know now, I never would have left,” he bemoans. “You were right there in front of me and I didn’t see you,” he opines. Sandler’s protagonist never stops articulating the film’s main points, and neither does Hanus, who tells his human compatriot, “You need to come back with a very different discovery, but all you can see is yourself.” This is far more irritating than Hanus’ goofy fondness for calling Jakub “skinny human,” and it grows more pronounced as Spaceman nears the Chopra Cloud, whose ancient particles are, per Hanus, from “The Beginning” and, therefore, destined to help Jakub get in touch with the origins of his own feelings for Lenka. Cue uncontrollable groaning.

Adam Sandler

NetflixRenck vainly reaches for operatic grandeur by cutting away to CGI vistas of the Chopra Cloud (and, also, by peppering his soundtrack with opera), and with a late sequence, he provides his own weak 2001: A Space Odyssey-esque voyage through cosmic time and space. Those gestures, however, are as mechanical as the film’s melodramatic maneuvers. Even with Sandler doing a serviceable downbeat-loner routine and Mulligan matching his every gloomy look, nothing about Spaceman is enchanting and even less resonates as moving. It’s a sad space trip that so desperately wants you to know that it's sad, and to feel its sadness, that it just winds up being the absolute wrong kind of sad.