Of The Boys’ many viscerally upsetting scenes starring its sadistic superhuman protagonist Homelander (Antony Starr)—pressuring a suicidal woman into jumping off a building; abandoning a nosediving plane full of passengers to their deaths; threatening to harvest his captive teammate’s eggs—one of the most jarring in Season 4 achieves that same unsettling effect precisely because of how utterly powerless it renders him.

“Why am I not good enough for you?” the supe asks his young son Ryan (Cameron Crovetti) at the end of Episode 3. His mouth is downturned, eyes watery, anger giving way to deep hurt. It’s a display of pained vulnerability so primal, your first instinct is to assume it’s a well-calibrated performance meant to manipulate the child’s emotions. But that isn’t the case; this is a genuine moment of vulnerability. While decades of corporate control and celebrity image management have taught the superhero to mask his barely restrained rage, he’s increasingly beginning to erupt with it. Open displays of needy petulance, though? Those are rare.

So far this season, Homelander has been needled by his graying hair, a betrayal of the lab-manufactured peak physical status he’s long taken for granted. Now, his churning insecurities—his lack of control over his son exacerbated by the loss of control over his own body—have finally come to a boil. He’s upset that, despite ensconcing Ryan in Vought Tower’s chrome cage, plying him with all the comforts a teenage boy could want and systematically poisoning his mind, the boy still seeks out the company of his surrogate father William Butcher (Karl Urban).

Homelander’s pleading (to a child, no less) is a change of pace for The Boys, a show populated by closed-off, hardhearted parents who perpetuate cycles of cruelty and violence. Think of Sam Butcher (John Noble), who credits the abuse of his children with making William tougher, never mind that it drove his other son Lenny (Jack Fulton) to suicide. Then there’s Homelander’s surrogate dad, Jonah Vogelbaum (John Doman). “When he was a little boy, 5 or 6, he was quite sweet,” the Vought scientist said of training Homelander. “I needed him to be the strongest man in the world…so I went to work on him.” (He never stood a chance, did he?).

And what of Homelander’s biological dad, Soldier Boy (Jensen Ackles)? Confronted with the son he never knew begging for them to finally unite as a family, all Soldier Boy can do is sneeringly call him “weak”, “sniveling,” and, ultimately, “a fucking disappointment.” In doing so, Soldier Boy echoes his own father, whose cruelly impossible standards and subsequent, incessant disappointment meant he grew up crushed by the weight of toxic masculinity. Years later, he’s unable to acknowledge his PTSD, since this would mean piercing his armor of cultivated stoicism.

In The Boys, even well-intentioned, protective parental actions are couched in the language of physical violence. Take the scene of Victoria Neuman (Claudia Doumit) injecting her daughter with Compound V in Season 3, inducing superpowers in her to make her stronger; to do so, Victoria holds her down, as her body painfully contorts with the effects of the serum. And in Season 3, Homelander abruptly shoves his son off a roof to get him to fly—not quite the actions of a loving father.

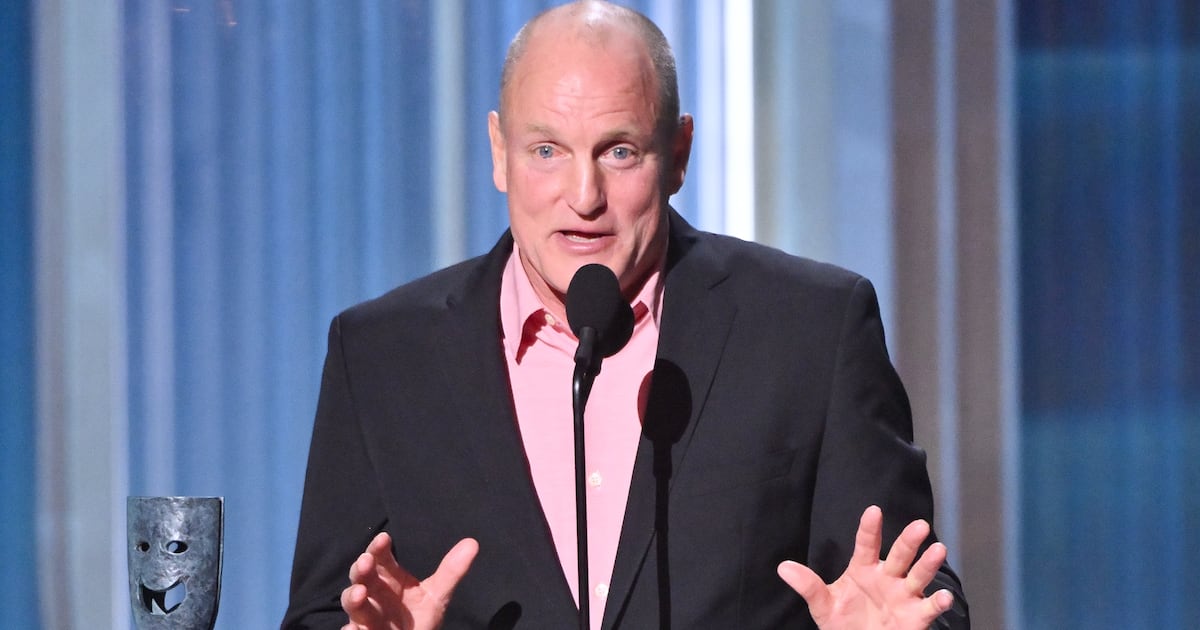

Homelander and Ryan.

Jan ThijsThe spinoff series Gen V continues this trend too, framing its parents as more obsessed with the image that their children project than the collateral damage it causes them. Little Cricket’s (Lizzie Broadway) mother not only controls her caloric intake, but also teaches her how to purge, leading to her subsequent struggles with bulimia. And when it’s revealed that the prolonged use of Andre Anderson’s (Chance Perdomo) powers will eventually kill him, his father Polarity (Sean Patrick Thomas) is still insistent that he take over his superhero mantle.

Season 4’s third episode, however, makes room for warmth over unrelenting psychological warfare. The cocksure Butcher finally admits to Ryan that he’s terrified of his impending death, even though he does try to bluster through the conversation with a show of bravado first. “Lost me bruv, your mum, and I could be leaving without making things right with the one part of her that’s still alive. And that scares me more than anything,” he eventually confesses. It’s a moving speech about legacy that just might cause Ryan to consider his own. At the end of Season 3, as he watched Homelander laser through a man’s head in broad daylight, his slow-creeping smile suggested he was open to the allure of violence. But Ryan is now wavering from that path the longer he spends under Homelander’s death-grip control, and with Butcher’s contrasting gentleness. Episode 3 also grants Hughie (Jack Quaid) closure for his parental trauma, in the form of a conversation with his mother who abandoned their family when he was young. Years later, he now knows why she had to leave: an all-consuming period of depression.

That’s not to say that flashes of vulnerability don’t otherwise peek through The Boys, though this is a show in which gut-spilling is more literal than figurative. In subverting what we’ve come to expect from the show’s parents and making some of its fiercest characters more open this time around, the results are surprising, mature, and incredibly affecting. In a season that so far has found itself retreading old themes and ideas about corporate politics, American fascism, and the manufactured nature of celebrity, what a relief to spend time with characters who can finally take the mask off.