Alzheimer’s disease is a curse that robs people of themselves and those they cherish, and The Eternal Memory is a heartbreaking account of one couple’s ordeal with the ruinous condition. If an inevitable tragedy, however, Maite Alberdi’s documentary—winner of the Grand Jury Prize at this year’s Sundance Film Festival—is not simply a record of pain and sorrow, given that it doubles as a portrait of true love in all its unbreakable, indefatigable glory. It’s a testament to the vitality and fragility of memory that itself serves as an act of preservation—of a prized past, a fraught present and an everlasting devotion.

The Eternal Memory (in theaters Aug. 11) opens with Paulina Urrutia in bed beside her slumbering husband, Augusto Góngora, who wakes and with good humor asks, “What happened?”, “What are we doing here?” and “Who are you?” Laughing, they shake hands while introducing themselves to each other. At this point, Augusto appears to know himself—or at least, enough of himself to state, “That’s me. I’m Augusto.”

Yet how much more he discerns about his life remains unanswerable, so director Alberdi fills in key gaps through quick glimpses of Augusto’s work as a journalist in his native Chile, reporting on strikes, protests, and other hot-button sociopolitical topics during Augusto Pinochet’s dictatorial reign. On camera as a young man, Augusto praises “democracy, freedom, justice, and solidarity” as the soul of Chile and all Chileans, although the ensuing film suggests that, in his case, love— embodied by Paulina—is truly at the center of everything.

An actress who served as state culture minister, Paulina is Augusto’s wife of three years and partner of more than two decades and it’s clear from the start that she’s his caretaker and surrogate memory, coaxing him to recall his job, his two children, and his siblings. Discussing the length of their relationship, and the fact that they’re in the house they built together, is Paulina’s means of both maintaining what Augusto still has and trying to rebuild what he’s slowly losing.

Since Alzheimer’s is irreversible, her efforts are destined to end in failure. Nonetheless, that doesn’t mean they’re without practical purpose in the here and now; Augusto, after all, is still with her, and wants to be whole, just as she wants him to be capable of functioning as best as possible. Moreover, they’re gestures of grace, providing him with the comfort and reassurance that, in his deteriorating state, he desperately needs.

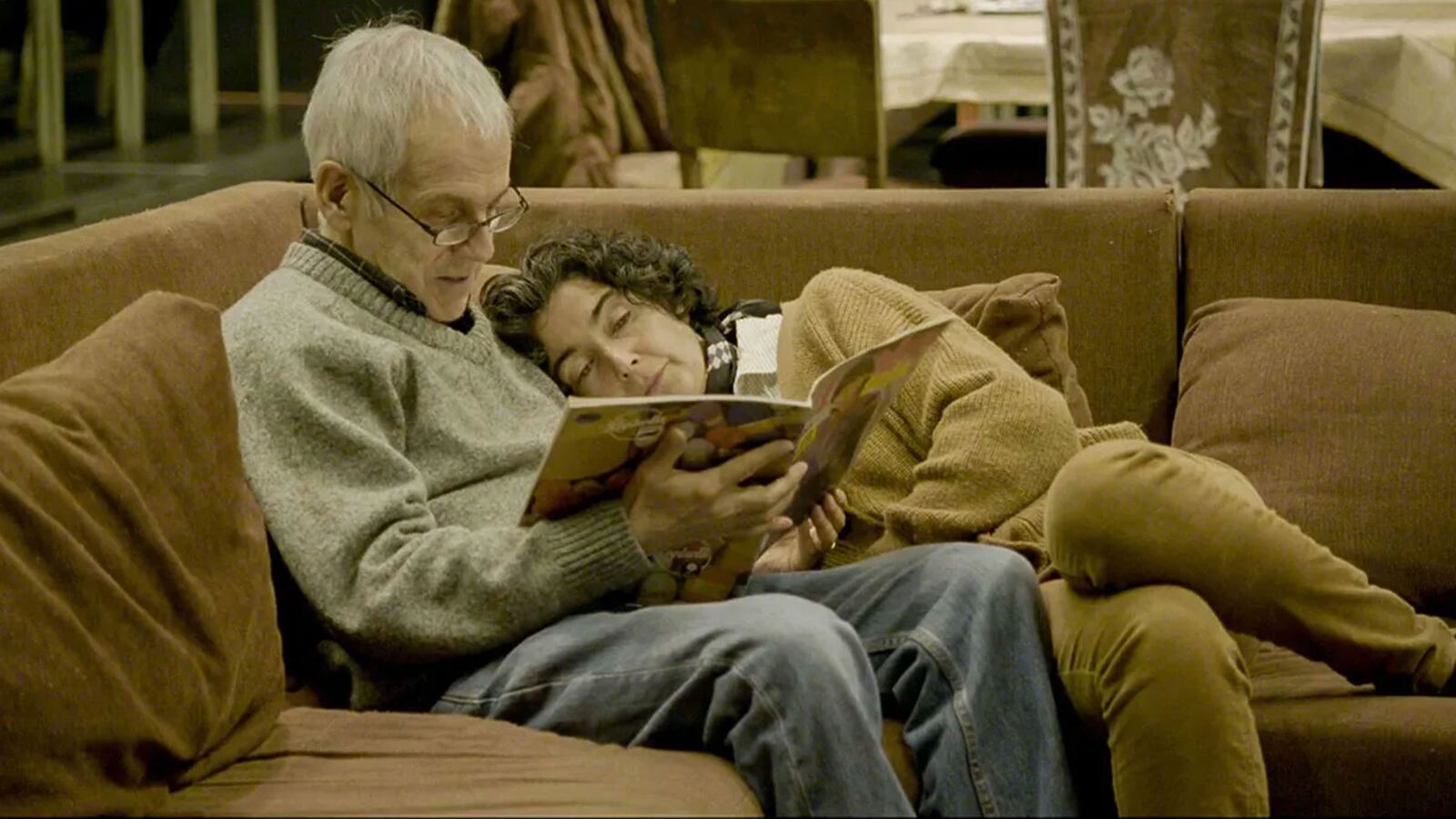

The Eternal Memory is a movie made up of small incidents and interactions, following the duo as they try to proceed forward even as Augusto slowly recedes within. On a walk through their quiet neighborhood, they hold hands as Paulina reads a book about a king and a knight (“One must be alone to be able to drop one’s armor”). At a rehearsal for her latest play, she recites lines as he sits nearby asking, “What’s going on here?” On stage, she muses (in character), “My memories are in music. In my garden, everything around me takes me to the past. Tomorrow will be a memory,” and Augusto watches and chuckles from the audience. Later, she asks her husband if he wants to die. “No, I don’t want to die,” he responds. “I love life,” and, despite having some problems, “What can you do?”

The specter of who Augusto was is ever-present in The Eternal Memory. A clip of Augusto acting for director Raúl Ruiz in Litoral is followed by an interview between the two, during which Augusto opines that the dead aren’t allowed to be dead in Pinochet’s Chile because they’re always missing or misidentified. Solace is in short supply in Alberdi’s documentary, so that when it does arrive—say, in the sight of Paulina helping Augusto shower or shave—it lands with overwhelming force.

Via snippets from his television program Teleanálisis, Augusto emerges as a man dedicated to bringing the lost, the hidden, and the forgotten to light, no matter the torment wrought by that process. Even today, some anguish never dissipates; watching old episodes of his program, Augusto is brought to tears when Paulina brings up his friend José Manuel Parada, who he learned had been brutally killed by reading it in the newspaper.

As he explains in an old television appearance, Teleanálisis was a chronicle of nearly 20 years of Chilean culture and society. The Eternal Memory bridges the gap between then and now, the political and the personal, to function as a complementary document of a man robbed of the very thing (memory) he viewed as essential. Yet simultaneously, the film recognizes remembrance as not only an individual but also a communal undertaking—a notion conveyed by Paulina’s tiresome (and, at times, tired) efforts to be there for her beloved.

It’s not an easy endeavor, especially as COVID traps them in their home and cuts them off from friends and relatives, and as Augusto’s condition worsens, stranding him in a mental fugue from which there is no respite or escape. In its concluding passages, Alberdi and Paulina present unvarnished views of Alzheimer’s nightmarishness: confused questions about fundamental aspects of reality; conversations with mirror reflections; and agonized laments (“What is happening to me?”; “I’m not well;” “I’m alone”) that can’t be satisfactorily consoled.

No matter the toll this takes on her, Paulina stays staunchly by Augusto’s side, soothing him during moments of perplexed distress with embraces and reminders “that Augusto is loved.” She’s the calm in the middle of their very intimate, insular storm, and Alberdi’s cutaways to home movies of happier, healthier times underscore the foundation of their bond. The Eternal Memory ends with visions of moving tenderness and grief, from the spouses standing head-to-head in foliage as Augusto tells Paulina that she’s pretty and thanks her for everything, to the couple caressing each other’s faces with their fingers as if to commit each contour, each wrinkle to memory.

Before that, though, it finds an ideal closing note courtesy of an inscription Augusto wrote to Paulina in his book about the Pinochet era, Chile: The Forbidden Memory: “There is pain here, the horrors are denounced, but there is also a lot of nobility. Memory is still forbidden, but this book is stubborn. Those who have memory, have courage, and are sowers, like you. You know about memory, you have courage, and are a sower.”

Liked this review? Sign up to get our weekly See Skip newsletter every Tuesday and find out what new shows and movies are worth watching, and which aren’t.