Jeremy Pope doesn’t so much reflect about his experience making The Inspection as preach about it. The film, which is out on Friday, is the first leading role for the actor, whose recent hot streak on Broadway (in the play Choir Boy and the musical Ain’t Too Proud) and on Netflix (Ryan Murphy’s Hollywood) earned him two Tony nominations and an Emmy nod in the span of two years.

He’s the kind of person who believes in moments, and this one—with this film and this role—feels just right. “For this to be my debut is an affirmation for me to continue to walk in step, because these things can and will happen,” Pope tells The Daily Beast’s Obsessed. “I talk about having to have an unbelievable amount of faith in yourself as an artist, and believing in things you can’t see. But it’s more so believing in things that the world isn’t ready to see for you yet.”

We’re talking in Georgia at the SCAD Savannah Film Festival, where Pope won the Distinguished Performance Award for The Inspection.

The film is written and directed by Elegance Bratton. It’s based on his experience as a young man who became homeless 20 years ago when his mother kicked him out for being gay. He enlisted with the Marines to find structure and meaning in his life, despite it being the era of “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell.” Pope plays Ellis French, an avatar for Bratton, who struggles through the unforgiving, Full Metal Jacket intensity of boot camp, all while attempting to reconcile his sexuality and feeling desperate to forge a connection again with his mother, played by a nearly unrecognizable Gabrielle Union.

Pope came out as gay in 2013, when he was starring in Choir Boy, the play by Moonlight Oscar-winner Tarell Alvin McRaney about a member of a gospel choir at a preparatory school for Black students struggling with his sexuality. As Pope made phone calls to his family, friends, and collaborators, he referred to the process as inviting others to “come in” to his identity and experience, rather than coming out.

There were people over the course of his career who warned him against being public about his queerness.

“Graduating college years ago, it was that thing of, like, ‘Don’t be out,” he says. “Don’t, because you won’t get jobs. You won’t work. If people know that piece about you, there’s no success. I didn’t grow up seeing Black queer movie stars. It’s not a thing.”

If Pope’s work in The Inspection suggests anything, it’s that now it is.

There’s an incredible scene in The Inspection in which French and the closest thing he has to a confidant at boot camp, Raúl Castillo’s drill instructor Rosales, are in a van. French has just suffered an explosive breakdown. Rosales asks him why, given the tough time he’s been having, he wants to be a Marine.

French’s eyes immediately fill with tears. His mom won’t talk to him, he says. His friends are dead or in jail. He’s out of options in his life. “But if I die in this uniform, I’m a hero to somebody.” His life would have meant something after all.

“Elegance was homeless for many years and had reached such a desperate place that he believed that the world had showed him that ‘because I’m Black and queer, I die,’” Pope says. “But having that uniform, he could say, ‘When I die, I’ll at least matter to someone.’ That’s really tough to know, that that’s where his brain went. That [this option] felt more promising than the street that he had been living on for so many years.”

The scene is an emotional high point of the film. And, though the circumstances may be specific to Bratton’s life, which inspired the storyline, the sentiment is a powerful thing to understand: As Pope says, “To want to matter.” Getting to channel that desire and articulate those words was one of the most cathartic moments of his career so far.

“I’ve spent so many years being an artist and trying to navigate the business of Hollywood denying my Blackness and denying my queerness, because it didn’t feel like there was space for me,” he says. “And if there is space, it’s only a little bit. You can’t take up too much. So you adapt.”

But delivering that monologue in The Inspection connected him to something personal. “It’s about loving myself and respecting myself enough to realize there are certain relationships that I have that don’t serve that [love]. And because of that, I have to be willing to let them go. Because I need to continue to walk into my purpose. When I walk in my purpose, good things happen.”

That particular scene is a turning point for French, one that Pope recognizes, in some ways, from his own life and experience. “That is him stepping in his purpose,” he says. “Once I stepped into owning my Blackness and stopped being ashamed of owning my queerness, things began to happen that are very singular and tailored for me in my experience in my journey as an artist.”

Roles like the one he played in Choir Boy, for example, or the one he played in Hollywood—a gay, Black aspiring screenwriter in a fictionalized version of the Golden Age of Hollywood—didn’t exist before. A show like Pose, which he joined for its final season, didn’t exist before. The industry is changing and opportunity is expanding, but it also requires artists brave enough to be “firsts” at the forefront of that change. They face the unknown of what could happen, but also the thrilling possibility.

“I feel very grateful because I couldn’t see this when I had my head down,” he says. “I think about, if only I had seen something like Choir Boy or The Inspection, how I would have been able to just open my eyes a bit sooner. And maybe I wouldn’t have spent so many years hiding and shape-shifting to be some version that isn’t me for some other person who doesn’t ultimately serve me, isn’t going to protect me, and doesn’t ultimately love me.”

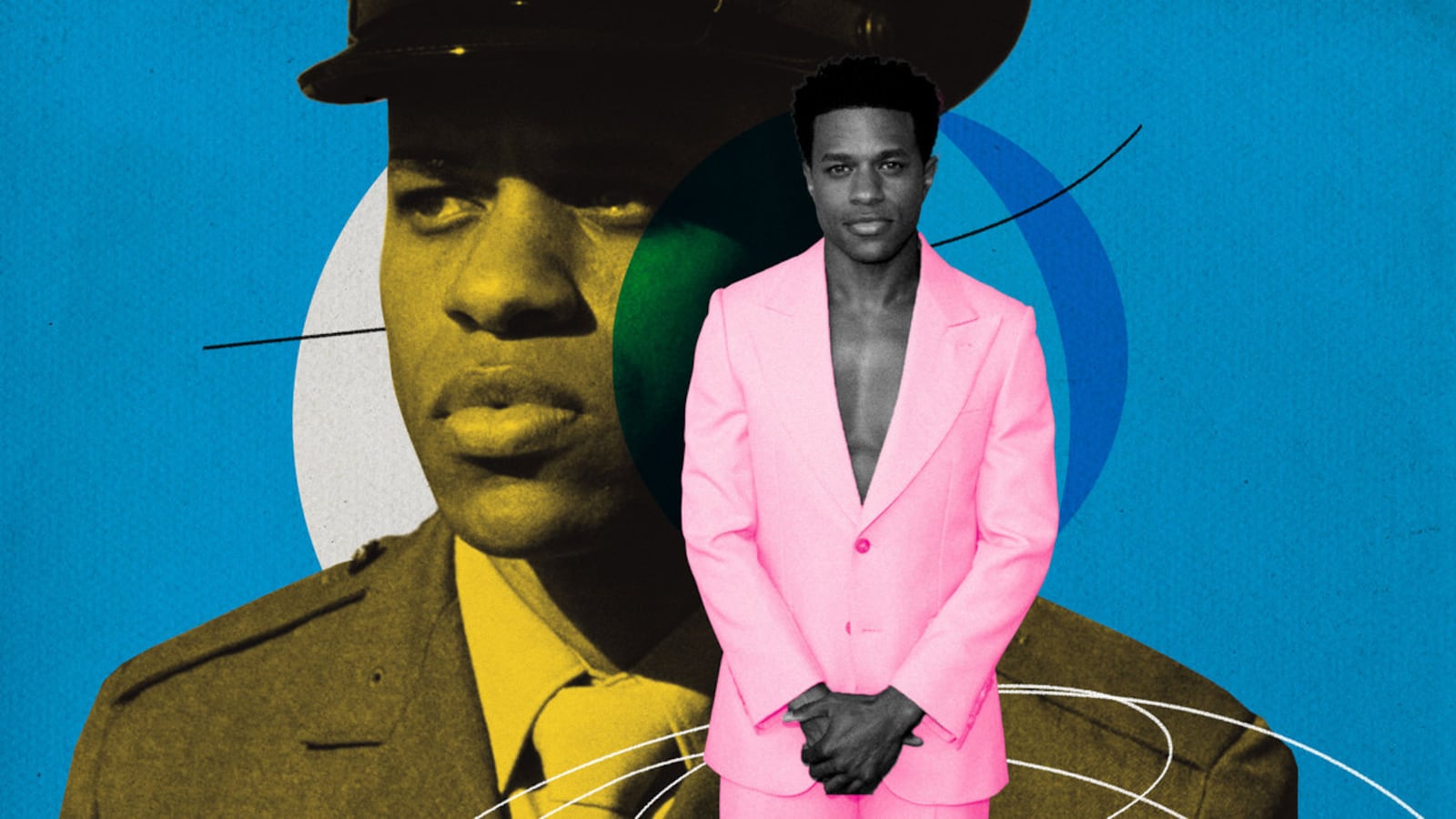

And what those people all those years ago had warned him about—that if he took public pride in all aspects of his identity, that he would limit his career—has proven demonstrably false. In 2019, for example, Pope didn’t just star in Choir Boy. He played a member of The Temptations in Ain’t Too Proud, and was Tony-nominated for both. He co-starred as Jackie Wilson in 2020’s One Night in Miami. He’s about to star as artist Jean-Michel Basquiat in a stage and upcoming film production, The Collaboration.

“It’s showing me that both can exist, that I can do both,” he says. “That your queerness isn’t your only identity. There were people who were like, ‘Don’t let them know about that [part of yourself]. Because then you’ll only be that.’ I’m not only that. That’s just a layer to my experience.”