Osgood Perkins has made a beast of a film with Longlegs, which stars Maika Monroe, Blair Underwood, and Nicolas Cage. The horror thriller is a procedural in the vein of The Silence of the Lambs, but offers up a singularly chilling experience. You’ve likely heard about the movie for months, thanks to distributor Neon’s extensive and creepy promotional campaign. Now, it’s finally in theaters. It’s one of those special films that’s best to go into blind, without learning too much about the plot. And Longlegs sets you up for 101 minutes of sheer terror right from the jump, with its nerve-shredding opening scene.

(Warning: Spoilers ahead!)

Longlegs begins in a 4:3 ratio, which conveys an immediate claustrophobic feeling, the negative space of the black bars on either side of the image threatening to swallow it whole. We start with a shot of a car’s front window as it makes its way through a quiet street. There’s an unsettling stillness to the image, as if you can’t quite tell if the car is moving or not. The footage sepia-toned, like an old photograph—a relic from the past. Slowly and steadily, the shot is saturated from that sepia coloring into the cool, icy winter that sets the scene.

The film then cuts to a young girl standing outside on a snowy front lawn. She’s in front of a towering white farmhouse; if the mood wasn’t already so unsettling, it certainly becomes so at this, what should be a charming, picturesque sight. There’s an eerie silence—nobody else seems to be around. If you’re familiar with the horror genre, you’ll know that a solitary child is usually a really bad omen, to put it lightly. But director Osgood Perkins enjoys toying with his audience’s expectations, and it turns out that a girl on her own will prove to be the least creepy part of this chilling scene.

The girl notices a car has appeared in the driveway. Realizing it’s not a car she recognizes, she takes stock of her surroundings, which are mostly dwarfed by giant evergreen trees which feel especially intimidating in the limiting 4:3 image. The camera shows us her perspective, and the shots of the trees—a typically relaxing sight—are accompanied by loud, threatening bursts of music, like a blowing horn. Everything feels off as the music plays— even the sounds of the horn feel distorted, like a warning siren that this girl should run for her life before it’s too late.

The warning was certainly warranted: A voice begins to stir behind her. It’s difficult to process; there’s a shaky breathlessness to the words, and their tone is pitched uneasily high as if the person is forcing themselves to speak in a different register than what comes naturally. The tension is at a fever pitch as you can’t help but fear for this girl's life—but perhaps more importantly, there’s a need to see who, or what, exactly, is speaking to her.

Just when you think you can’t grip the armrests any tighter, Perkins masterfully manipulates our expectations, refusing to reveal the person’s face. We see a close-up of this person from nose to knee, just off-center in the frame.

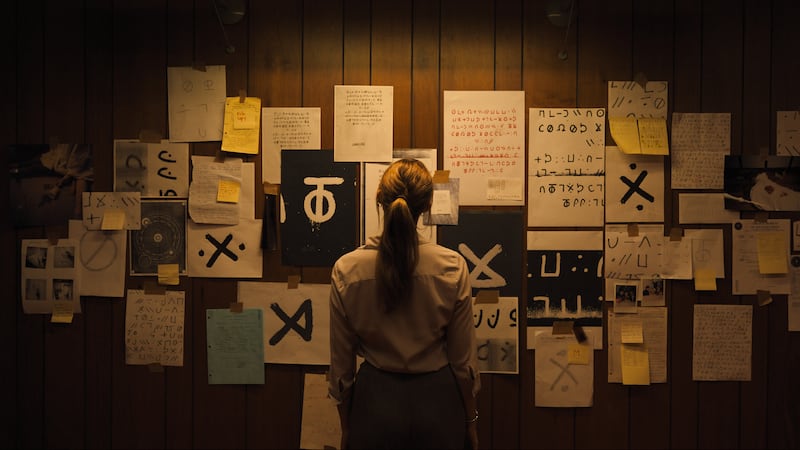

Maika Monroe in Longlegs.

NEONUp until this point, Perkins has shown us everything we could possibly want—we were about to see everything the girl could see. Suddenly, the stakes have risen from uneasy tension to an unbearable one, as the thing we want to see the most—the face of the person speaking to the young girl—is completely hidden from us. Longlegs gives the viewer a certain level of freedom and access in its opening minutes, and then yanks it away at the moment we crave it most. Visibility turns to obfuscation, and the effect is maddening.

Even what we can see feels off. The girl’s face is one of confusion and discomfort, as she tries to keep those feelings at bay to not upset this person speaking to her. What we can see of this person is even stranger. Their clothes don’t seem to fit properly. They’re tight and suffocating like the 4:3 aspect ratio. The colors—pinks and blues—have faded, as if the jacket was first worn many years ago and was outgrown by the person wearing it before this girl was even born.

What we can see of the person’s face doesn’t exactly instill comfort. It’s hard to discern their gender, as their face seems bulbous and inhuman, as if it’s been poked and prodded by needles and injections to create an unnervingly unnatural shape. Their voice too, is inexplicable, like a man deliberately trying to sound lighter and more feminine to give an air of calmness and comfort. It comes off as a performance, perhaps meant to convince their prey that they are in safe hands before it’s too late to get away.

“I wore my longlegs today,” the person says, suddenly jumping down to meet the girl's eyeline, mouth ajar, contorting into an open-mouth smile. It’s then that Perkins’ camera finally reveals this person’s face. They stare her, and the camera, straight in the eye, but only for a second before the scene ends. It’s just enough for a chill to tear down your spine—it’s abundantly clear that something is seriously askew here. There’s not enough time to take in the details, but it’s a face that hardly seems human, and, combined with the ill-fitting and faded clothes, it’s suddenly obvious that this is an incredibly threatening person. This is Longlegs, and he’s terrifying.

It’s one of those setups that so effectively rips through the screen, telegraphing straight-up evil. I had fallen under the spell of Neon’s singular and intense marketing campaign, and I’d seen and enjoyed all of Perkins’ previous films. But this first scene in Longlegs is scarier than anything in his last three films. After mere minutes, I was left with a pit in my stomach and an overwhelming thought: “Am I brave enough for this?” Either way, Longlegs was just getting started.