As one character opines in The Offer, you don’t need to know how art works to enjoy it, and yet Paramount+’s series about the making of The Godfather—timed to coincide with the film’s 50th anniversary—believes the exact opposite. Akin to the studio giving itself a big sopping wet-tongue kiss in the mirror, this 10-episode streaming affair (premiering April 28) is a cinema-loving counterpart to HBO’s recent Winning Time, operating as a cartoony behind-the-scenes look at a pop-culture sensation that articulates everything in bursts of groan-worthy exposition delivered by cornball caricatures. Early on, its protagonist remarks about the unparalleled power of the movies, “You can’t get that experience in television—you’re just in your living room looking at a small fucking box.” These proceedings prove that to a tee, imparting infinitely less than one could glean from spending the same amount of time simply watching The Godfather trilogy instead.

Fashioned as a flattering The Little Engine That Could-style narrative, The Offer is obsessed with both leadenly explaining The Godfather (and various other ’70s classics) to its audience—be it the importance of their scenes, the reasons for their production choices, or their overarching themes—and drawing parallels between Francis Ford Coppola’s masterpiece and those who made it. It’s children’s book-grade cinema history and criticism, and at its center is Albert S. Ruddy (Miles Teller). Dissatisfied with his job at the Rand Corporation, Ruddy decides to try his hand at producing, and immediately strikes gold with TV’s Hogan’s Heroes. He has silver-screen dreams, though, which we understand because he tells his girlfriend Francoise Glazer (Nora Arnezeder), “I need to be in the movies.” Those aspirations come true when he gets a gig at Paramount working for Robert Evans (Matthew Goode), who no matter Ruddy’s failure with Robert Redford’s Little Fauss and Big Halsy, gives him a shot at adapting Mario Puzo’s (Patrick Gallo) bestseller The Godfather, because as Evans states about the project, it could become a “cultural phenomenon” that’s “Rosemary’s Baby, but bigger!”

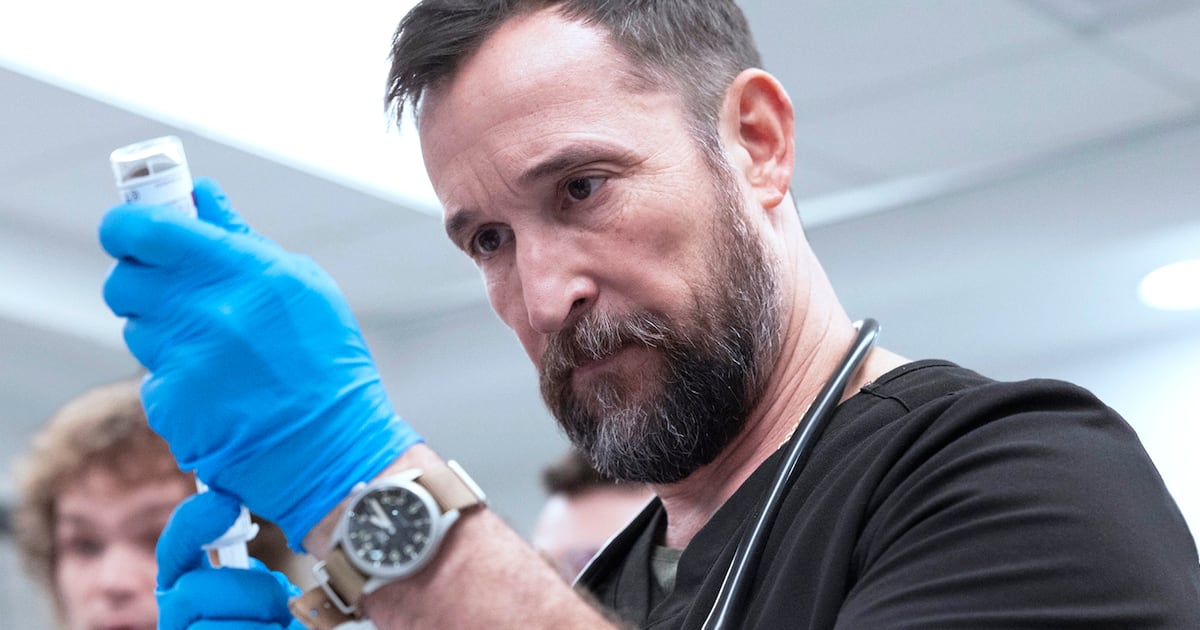

The Godfather may be a hit with readers, but it’s viewed as a dicey proposition by the studio, which is run by imperious Gulf & Western bigwig Charles Bluhdorn (Burn Gorman) and his corporate minion Barry Lapidus (Colin Hanks), the latter of whom eventually devolves into such an anti-art, bottom line-driven clown that he actually utters things like, “We should be making what the people want to see!” and “I’m not greenlighting anything I don’t understand!” The system is against this upstart endeavor, but Ruddy is so calm, cool and confident that he won’t be deterred, and he’s aided in his quest by secretary Bettye McCartt (Juno Temple), who knows everyone and everything going on in the industry. Together, they concoct a plan that must be fought for at every step, beginning with the hiring of writer/director Francis Ford Coppola (Dan Fogler), enlisting Puzo to co-pen the screenplay, casting untested Al Pacino (Anthony Ippolito) as Michael Corleone and wild card Marlon Brando (Justin Chambers) as Don Corleone, shooting with deep Caravaggio-inspired shadows with cinematographer Gordon Willis (T.J. Thyne), and filming key scenes in Sicily.

The Offer knows its lore and packs tons of details, anecdotes and analysis into its 10 installments. However, it does so in an absurdly blunt and cheesy manner, such that it resembles a parody of prestige awards bait—and thus the exact opposite of The Godfather, no matter how doggedly it tries to ape that epic’s aesthetics and connect its principals to its subject’s fictional characters. Ruddy, Evans, McCartt, and Coppola are all “family,” Evans is literally called “The godfather of The Godfather,” and at a premiere screening of the film, the camera pans to a close-up of Ruddy as we hear someone intone, “Don Corleone.” It’s embarrassing connect-the-dots plotting, and it extends to the fact that its four main characters are also constantly portrayed as kindred spirits with similar backstories, against-the-grain attitudes, and holy appreciation for the magic of the movies.

To further illustrate how The Godfather’s story and origins were alike, The Offer details Ruddy’s relationship with gangster Joe Colombo (Giovanni Ribisi), which develops due to objections to the book by Italian-Americans and, in particular, Frank Sinatra (Frank John Hughes), who doesn’t take kindly to its thinly veiled shots at him via the character of Johnny Fontane. Colombo’s war with Joe Gallo (Zack Schor), as well as his demands on—and funding of—The Godfather, pad the material but do little more than provide token, second-rate gangster drama. Moreover, by painting Ruddy as a genuine friend of the mob—to the point that he ultimately tells them that their approval of the film is what matters most—the show contends that The Godfather was designed to please and glorify organized crime. Still, for all the effort it expends on explicating The Godfather’s core ideas and controversies, Michael Tolkin’s series steers conspicuously clear of seriously investigating that topic.

Everyone involved in The Offer is in full hambone mode: Teller’s Ruddy is a guy who gets the job done and has balls (something referenced on at least three occasions); Goode’s Evans is a nasally wunderkind who’s as smart and smooth as he is volatile (especially once his marriage to Meredith Garretson’s Ali McGraw disintegrates); Ribisi’s Colombo is a growly facsimile of a mob boss; and Fogler’s Coppola is a dedicated filmmaker who comes across as far too goofy and lightweight to be a genuine artist. References to notable movies of the era are unremitting, and yet regardless of its familiarity with the decade, it all feels like pantomime, full of threadbare impersonations and over-cooked declarations about the significance of hit titles, the intersection of art and commerce, and the go-getter spirit necessary to turn fantasies into reality.

Even more grating than its creaky performances, its tell-don’t-show storytelling, its Film Studies 101 insights, and its enervating faux-conflicts (which are neutered by our knowledge of how the movie turns out), however, is the absence of a meaningful point to The Offer. Despite fixating on the minutia of Ruddy and company’s enterprise, Tolkin says nothing of import about it other than that it was tough to make, was often a lot like The Godfather itself, and defied the odds to become a timeless triumph. By the time it gets around to reveling in the film’s Oscar wins, the entire thing feels like a pointless act of self-congratulation on Paramount’s part.