With their new documentary The Space Race (premiering on National Geographic Feb. 12 and streaming on Disney+ and Hulu Feb. 13), directors Diego Hurtado de Mendoza and Lisa Cortés have a specific, admirable goal: to spotlight the under-discussed stories of Black astronauts during the height of NASA’s space program.

Through archival footage and contemporary interviews with principal figures, The Space Race traces a historical lineage from the early 1960s through the present day of Black pilots and engineers whose contributions to space exploration have been systemically marginalized for more than half a century. But while the film broadly achieves its aim of correcting a biased historical record by allowing primary historical actors to control their respective narratives, it falters structurally and tonally by adopting too broad a scope of inquiry.

The Space Race gets the most mileage from the extraordinary stories of two men, former test pilot Edward Dwight and former astronaut Guion Bluford. As he tells it, Dwight was selected to join the U.S. Air Force Aerospace Research Pilot School in 1961 largely because of political pressure from National Urban League’s Whitney Young, who pressed upon the recently elected President John F. Kennedy to find a Black astronaut. Dwight subsequently became both a political pawn of the government, as his selection into the program became international news, and a genuine pioneer who faced severe prejudice from within the program, including from commandant Chuck Yeager, who reportedly told the school’s staff and participants that “Washington is trying to cram a n----- down our throats.”

Sadly, Dwight was not selected by NASA to be an astronaut despite proceeding to Phase II of the program. After Kennedy’s assassination, his advancement was no longer a NASA priority. It would take another 20 years before the first African American would go to space; the man in question was Guion Buford, who was selected to be a member of NASA Astronaut Group 8, the first to include women and people of color, many of whom were recruited by Star Trek co-star and NASA volunteer Nichelle Nichols. He, along with other Black recruits Ron McNair and Fred Gregory, were in the program together and became icons. Buford, who states he didn’t particularly want to be “the first Black astronaut,” was chosen to go up with the Space Shuttle because of his prior flying experience, which set him apart from McNair and Gregory.

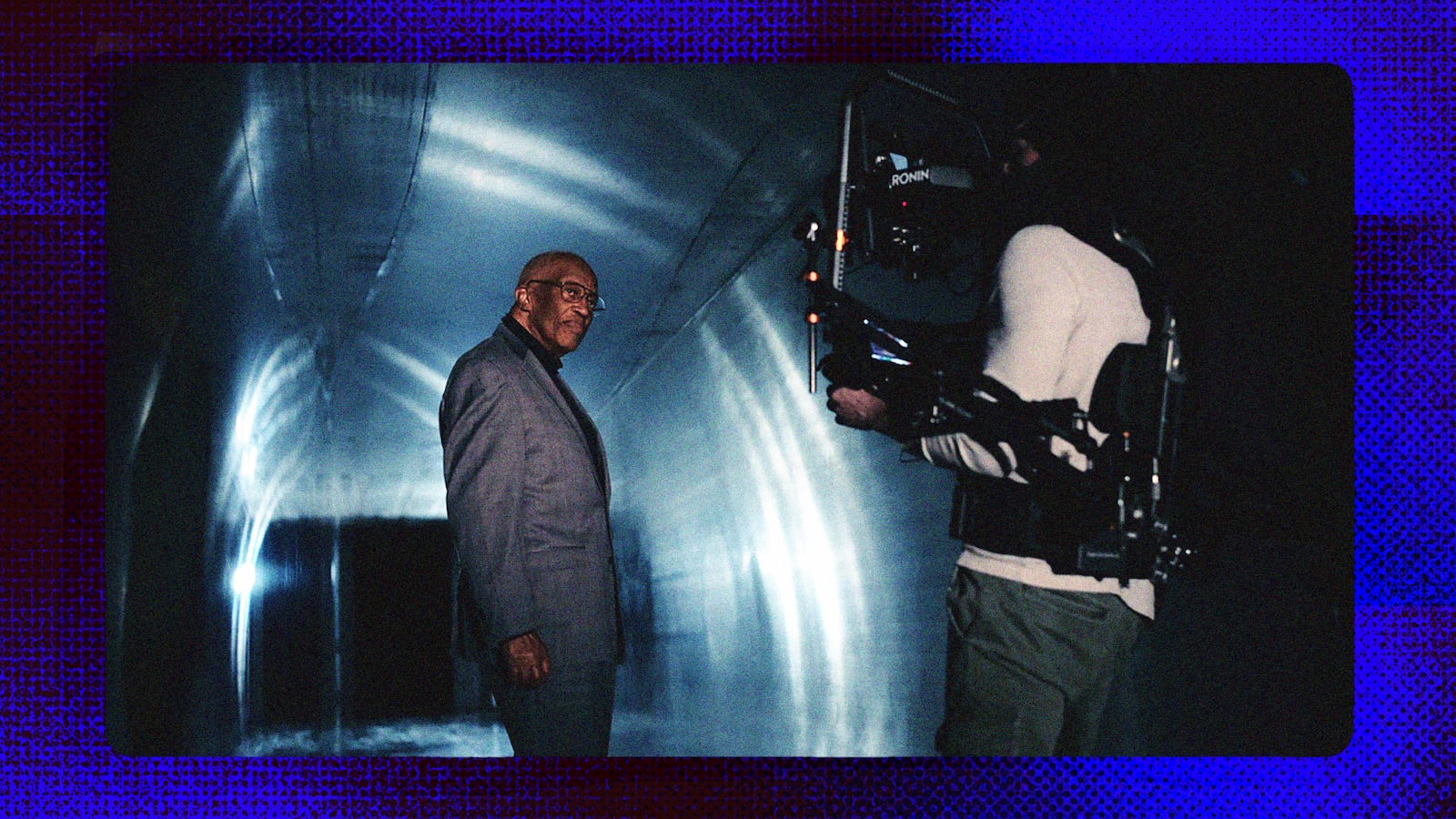

A self-described introvert and “average guy,” Buford comes across as a charming, grounded figure in The Space Race, someone who is well aware of his notable accomplishments while also feeling entirely indifferent to the spotlight. (“Sometimes I need to be reminded that I am better than I think I am,” he remarks at one point, humbly and affectingly.) Dwight—who, at age 90, has lived multiple impressive lifetimes and currently works as an accomplished sculptor—is a similarly compelling interview subject, complete with a remarkable memory. He accepts his belated recognition as a trailblazer with good humor and without an ounce of apparent bitterness, despite being well within his rights to express contempt towards a system that denied his shot at history.

Although The Space Race neatly incorporates other voices into the fold, such as former Administrator of NASA Charles Bolden, it struggles to maintain focus. Its brief digressions into ancillary topics, like Afrofuturism, feel like paltry, compulsory inclusions. These occasional detours suggest that the filmmakers felt an anxious pressure to incorporate every story of Black excellence, and ended up checking boxes.

The mid-narrative insertions of Robert Lawrence, who would have become the first African American in space if he hadn’t been killed in a plane crash in 1967, and Arnaldo Tamayo Méndez, technically the first person of African descent to enter space through the Soviet Union’s Intercosmos program, ideally should have been expanded upon and weaved throughout the film, especially since they both neatly dovetail (or contrast) with Dwight’s experiences as an arm of the government’s propaganda machine. Instead, The Space Race gestures towards the connection but doesn’t explore it, ironically treating both men’s stories like footnotes on a larger narrative.

Astronaut Ed Dwight is interviewed in The Space Race.

National GeographicThe choices The Space Race makes with editing, writing, and direction are political in their own right. The film’s directors and participants allude to the Black Power movement and inter-community opposition to space travel on economic grounds in the ’60s (best embodied by Gil Scott-Heron’s spoken-word poem “Whitey on the Moon,” which goes curiously unmentioned), but the acknowledgment feels obligatory, and the absence of any substantive commentary about it can’t help but look glaring considering that the film places so much weight on the power of symbolic representation. (It’s unclear whether NASA’s participation in the film’s production influenced these decisions.)

When The Space Race reaches the present day, the film recognizes the weight of George Floyd’s murder and subsequent protests, mostly via the words of Victor Glover, who was stationed on the International Space Station in 2020. He responds earnestly about his feelings of anger and sadness while being millions of miles away from the situation, but within the context of the film—which has detailed the Challenger disaster and truncated the contributions of other Black astronauts into a montage—it can’t help but feel like another belated illustration of how NASA engaged with civil rights.

One could argue that a feature-length film can’t possibly be expected to give all these stories their proper due, and their inclusion, however brief, gives viewers an introduction for their own personal research. But in order to effectively highlight the stories of these pioneers, and the larger systemic context from which they arose, the medium has to properly support the message. The Space Race’s alternately plodding and discursive structure doesn’t do them many favors, and though it might succeed as a modest primer and tribute, its ambition to reach so much higher only emphasizes its flaws.