(Warning: Spoilers ahead for the current season of The Traitors.)

Television has never seen a social experiment quite like The Traitors. In Peacock’s hit reality competition series, stars from TV franchises as varied as Survivor, The Real World, Big Brother, Love Island, and The Real Housewives gather in a Scottish castle to partake in a modified Werewolf, a party game in which villagers must seek out the monster among them before they are picked off one by one. Because the contestants are given no clues as to the titular tricksters among them, misinformation and groupthink run rampant. Although the players fancy themselves astute judges of character, the delight of watching The Traitors is that the series reveals that people are rarely as smart as they think they are. Almost every Faithful, the show’s preferred sobriquet for its helpless innocents, join the show thinking they will very easily detect the liars among them. Most are pretty terrible at this, with a notable exception being the contestants from the show’s New Zealand offshoot, who are all so good it makes the show dull.

But among the maelstrom of buffoonery and hysteria, The Traitors has carved out a unique space for its LGBTQ+ cast members, who are subtly challenging the unwritten rules of queer media representation. If The Traitors thrives on treachery and deception, few seem more up to the mission than its LGBTQ+ hopefuls, who are more than ready to engage in some playful backstabbing in pursuit of outrageous fortune. The series’ willingness to let queer people get a bit nasty and dirty—but in a wholly low-stakes manner—is so enormously appealing because it offers something rarely seen on television: LGBTQ+ villains we can actually root for. We are allowed to love them and despise them (or perhaps feel a mixture of the two) without it being a comment on all queer people or a referendum on whether an entire community deserves rights, as has been the case too often in the past. Straight, cisgender people—particularly white men—have gotten to break bad for as long as popular media has existed, and The Traitors shows that queer people are ready for their chance.

Parvati Shallow

PEACOCK/Euan Cherry/PeacockNo person in recorded history has relished the opportunity to play the heel more than Parvati Shallow, the Survivor alum who came out as queer shortly before the second U.S. season of The Traitors (which currently counts 21 international franchises, including two competing versions in both Canada and Belgium). Shallow was once named by Survivor host Jeff Probst as his favorite winner in all 45 seasons of the show, so it perhaps goes without saying that she is tapped to be a Traitor. Practically licking her lips the evening of the first murder, she would be entirely wasted as a Faithful. The others in her wicked clique are Big Brother winner Dan Gheesling, whose truncated tenure on the show was defined by overestimating his dexterity with deception, and Real Housewives of Atlanta legend Phaedra Parks, the G.O.A.T. of Season 2 and a human pull-quote machine. (Her ice-cold delivery of “not my Bergalicious” is one for the reality TV record books.)

Shallow is routinely outclassed in manipulation by Parks, who proves that mere mortals shall never put one over on a Housewife, but our dear Shallow makes up for in sheer chutzpah what she lacks in Bravo basic training. She is just having so much fun on this show, whether it’s christening a beloved circlet as her “predatory headband” or slipping Love Island winner Ekin-Su Cülcüloğlu a poisoned chalice to eliminate her from the game. (The latter move inspired another all-timer from Parks: “Not Ekin-Su. Lord, not Ekin-Su.) Shallow was sadly eliminated in the show’s most recent installment, having lost the trust of the castle’s other inhabitants several episodes back. How could they ever believe she was anything but a Traitor when this was the part she was so clearly born to play? But with her Medusa squint and Machiavellian desire to banish faithfuls, Shallow succeeded at something much more important than winning a $250,000 jackpot. She was fully aware that she was there to produce not only good television but also great camp. By that count, every frame that she graced the screen should be hung in the Louvre—long may she live.

Most international editions of The Traitors feature at least one queer villain, to admittedly varying degrees of quality. It’s clear right away that Miles Asteri, a lovely nurse who appears in the second U.K. season, isn’t long for this show because he commits a cardinal sin: He is too nice. (The RuPaul’s Drag Race alum Peppermint, a Faithful eliminated first in season two of the U.S. edition, suffers from a similar predicament.) Conversely, Alexandra Duggan is one of the best Traitors the show has ever seen. A lesbian model recruited late in Australia’s inaugural season, she takes duplicity like a hot knife through a pad of clueless butter. Her secret to being such a smooth operator, as Duggan herself remarks, is that no one around her sees it coming. She’s a beautiful girl with a sweet disposition, and people have underestimated Duggan her entire life, thinking her innocent and simple. They haven’t grasped what she is capable of, and in her 11th-hour turn to the dark side, she is only too happy to demonstrate what everyone has been missing.

If the thrill of seeing someone like Duggan deceive cishets to win herself a giant pile of money has a Saltburn air about it, its appeal explains why LGBTQ+ viewers have been so drawn to the recent wave of queer villains in film and TV: We know there’s so much more to us than the restricted view others see. Representation has long been a critical vehicle for equality, but that kind of power comes with great stakes. For instance, Mitchell (Jesse Tyler Ferguson) and Cam (Eric Stonestreet), Modern Family’s lovably bickering gay couple, were widely credited with changing America’s hearts and minds regarding same-sex marriage. When the long-running sitcom premiered in 2009, just 40 percent of households supported marriage equality, and by the time its final episode aired in 2020, 67 percent did. But even as the couple was helping to make America’s living rooms marginally more progressive, the ways in which their love could be portrayed was nonetheless limited. They didn’t share a kiss on screen until the second season, and whether the two men actually hate each other remained an open question among fans for the entirety of Modern Family’s run.

With so much pressure to be seen the right way by a public who decides what rights we get, the LGBTQ+ community still has a reasonable fear of being seen in a way that might set back our hard-won progress. Because of that anxiety, our representation can sometimes trend toward the safe and—dare I even say—boring. Our characters have to not only be good but they have to also be better than those around them: upstanding citizens and the world’s moral arbiters. Glee was groundbreaking in its depiction of the everyday life of the once-closeted Kurt Hummel, played by Chris Colfer in an Emmy-winning performance, but the show tended to portray him as cartoonishly perfect, as if he were auditioning for the lead role in 16 Going on Sainthood. Queer characters are rarely afforded the opportunity to be anything less than an aspirational ideal, seldom allowed to be as beautifully messy as LGBTQ+ people are in our real lives. We should surely get the chance to be heroes and champions, but we should be permitted to be everything else, too.

Tom Hollander as Truman Capote

FXAnother key reason that we, for a very long time, saw so few great queer villains is that they have often been done so poorly—exploited as a tool to scare a public that knew virtually nothing about our lives. The uneasy and unfamiliar is the backbone of horror, after all. Whereas the queer villainy in the thrillers of Alfred Hitchcock was always coded, Brian de Palma’s Dressed to Kill made those themes overt, casting Michael Caine as a murderous transgender psychopath. When conceiving of the seven-foot tall Xerxes (Rodrigo Santoro) in 300 several decades later, director Zack Snyder said his intention was to repulse his straight male viewers: “What's more scary to a 20-year-old boy than a giant god-king who wants to have his way with you?” Queer villains have been similarly used to shock and titillate in films and TV shows ranging from Silence of the Lambs, Mr. Robot, Sleepaway Camp, Basic Instinct, Pretty Little Liars, and Ace Ventura: Pet Detective, and even to frighten children in Disney classics.

The queer symbiosis of The Traitors suggests that LGBTQ+ people are ready for representation that’s more complicated and depicts our flaws as individuals with nuance and respect. We’re getting there, even if progress is slow. The universe of Breaking Bad exhibited enormous care in establishing Gus Fring (Giancarlo Esposito) as a full individual before confirming that he is gay, waiting until Season 6 of its spinoff, Better Call Saul. While Killing Eve ultimately fumbled the bag of its central Sapphic romance, the joy is in Jodie Comer’s masterful performance as the aptly named Villanelle—at turns coy, vulnerable, and heartbreaking. Despite every horrible thing she’s done, the lives she’s ruined, Comer lets viewers fall in love with Villanelle anyway. If a psychopathic, murderous fashionista can’t find a little gay happiness, what good is this project of living? The memed embrace of The White Lotus’ famed “evil gays,” gruesomely slaughtered in a Season 2 shoot-out with doomed Tanya (Jennifer Coolidge), suggests that we are owning our queer villains in the cultural present, rather than needing to reclaim problematic characters decades later.

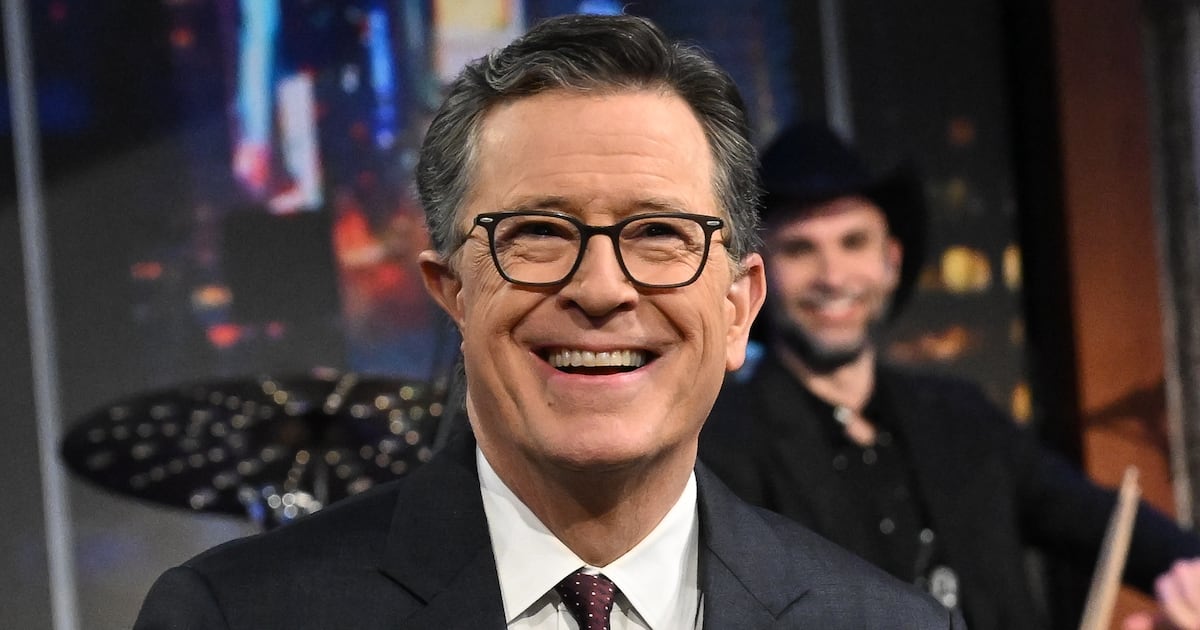

These characters succeed whether others have fallen short because they do not have to shoulder the burden of representation alone, not when we also have Darren Criss’ slinky killer in American Crime Story, Tom Hollander’s poison-penned Truman Capote in Feud: Capote vs. the Swans, and Andrew Scott’s conniving grifter in the upcoming Ripley. And the same is true of The Traitors. The sprawling cast makes room not merely for queer antagonists but a wide variety of archetypes that I’ve never seen on television before. The U.S. branch gave us Andie Thurmond, a winsome nonbinary jock, while Australia brought to the world stage Mark Norman, a leather jacket-loving twink slash walking lie detector. The U.K. edition features an utter embarrassment of queerness, with special mention going to Aubrey Emerson, an eagle-eyed retiree with a bottomless collection of fedoras and ascots. But towering above them all is the inimitable Alan Cumming, who lords over the American version as if Willy Wonka had just escaped an explosion at the tartan factory. In a choice Season 2 scene, the host informs his cast he won’t be helping them: “Don’t ask me, I’m just here to say cryptic things and look absolutely spectacular.”

In the Netflix documentary Disclosure, an excavation of the history of transness on screen, the actress and writer Jen Richards comments that every problem of LGBTQ+ representation is simply “more.” If few shows in recent memory have embodied the concept of “more” as much as The Traitors—where the Olympian Ryan Lochte once spent an entire episode searching for a secret door, apropos of who even knows—that very muchness gives its view of queer life a surprising depth. Duggan, our Australian Keyser Soze, is open about the fact that she joined The Traitors not out of a thirst for blood but because she and her partner hope to conceive a child; in-vitro fertilization is expensive, and they wouldn’t be able to afford the treatments otherwise. That backstory is crucial because it’s what so many queer antagonists have lacked: depth and humanity, the understanding that they are people, not sentient jump scares. What makes Duggan such a great villain is that, like many who came before her, she’s not really a villain at all. She’s just a girl playing a game, and for once, it was designed for her to win.