After 12 years, The Walking Dead has finally trudged its last step. On Sunday night, the series comes to a close after 11 seasons—and leading into the finale, the popular questions appeared to be the same as they’ve been for years: Who would die, which alumni might return, and would there actually be any closure?

Sunday’s finale brought to a close one of TV’s biggest contemporary sensations—the zombie drama to end all zombie dramas and a ratings juggernaut. Even as it’s dropped from 17 million same-day viewers for its Season 7 premiere to 2.2 million for last year’s Season 11 premiere (per Variety), the show has remained among the most-watched cable shows on television for same-day viewing—that is, when it’s not No. 1. But in spite of its continued cable supremacy, The Walking Dead has felt like a putrefying version of its former self for years. What, exactly, caused this slow death? One might blame cynical writing, the death of cable television as monoculture, or both.

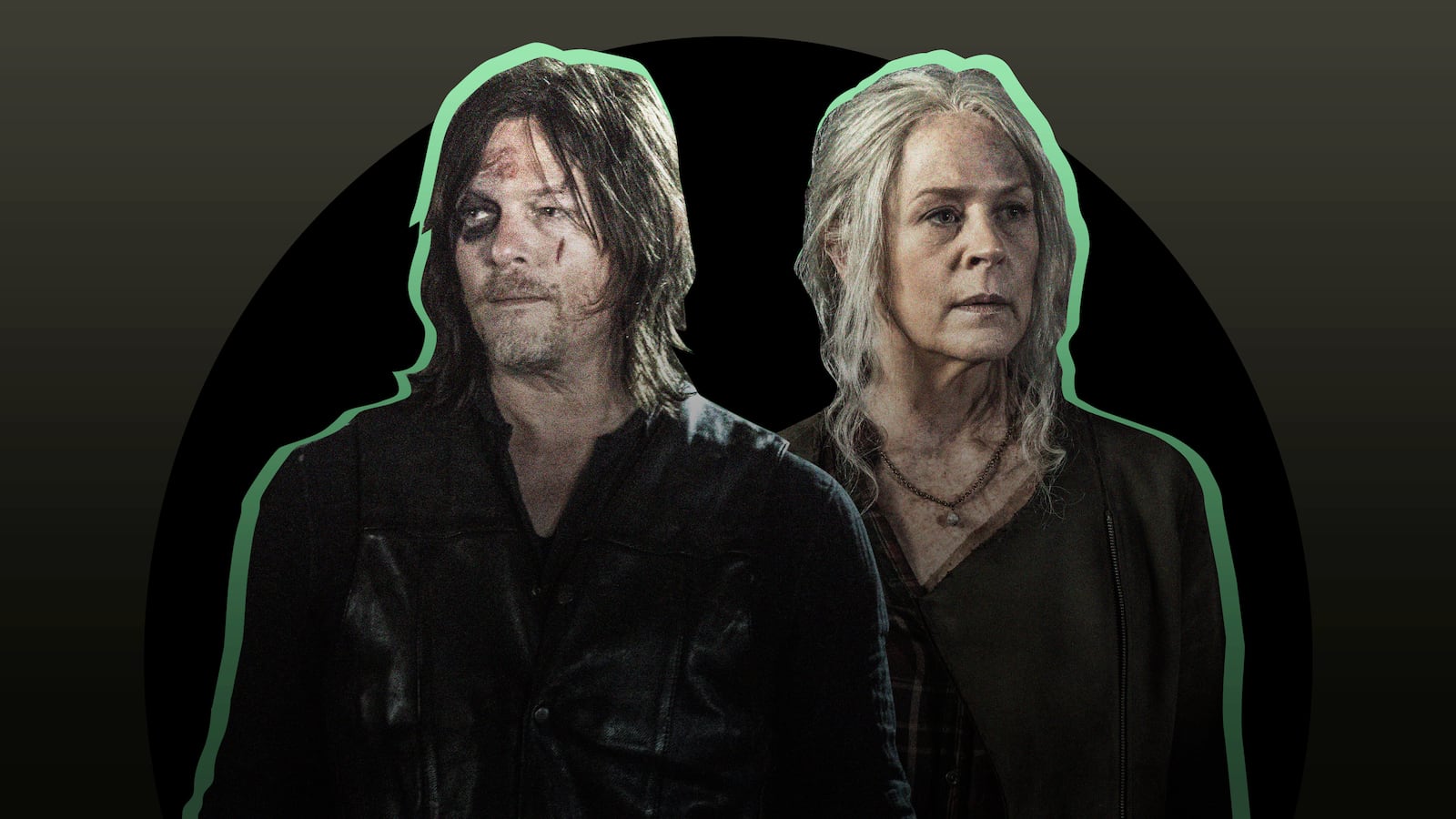

Norman Reedus as Daryl Dixon, Melissa McBride as Carol Peletier in The Walking Dead, Season 11, Episode 24.

Jace Downs/AMCBy the time The Walking Dead made its modest six-episode debut on Halloween in 2010, the TV-watching public was ravenous for zombie content. Books like The Zombie Survival Guide and World War Z lined the shelves of Barnes and Noble, and the undead had overrun the movies, too, with releases like 28 Days Later, Zack Snyder’s Dawn of the Dead remake, Resident Evil, and Zombieland. “Humans vs. Zombies” games were an epidemic on the nerdy corners of college campuses (I say this as someone who not only played but moderated these games, thankyouverymuch!), and watching TV while also feverishly chatting about the minute-by-minute drama online was still a relatively novel concept. And streaming had only just begun eating cable television’s lunch.

In stumbled The Walking Dead, which premiered one year after the H1N1 pandemic. (Remember swine flu?) The series became a massive hit, even in spite of a dismal second season, and for a while, TWD was inescapable. Spoiler blogs abounded, and the show—like its contemporary, Game of Thrones—was monitored so closely that it (like Game of Thrones) wound up shooting alternative endings for what became Steven Yeun’s now notorious death scene just to prevent it from getting spoiled.

Comic readers have known one ending to The Walking Dead’s story since 2019, when Robert Kirkman’s comic upon which the show is based came to a close. As always, however, AMC’s Scott Gimple has promised that The Walking Dead show will not take all its cues from the comics; the show’s ending, he told Entertainment Weekly, will be a “remix” of the original. (It would have to, given that Carl—who ends the comics by reading a book to his daughter, Andrea—has been dead on the show since Season 8.)

For all the years The Walking Dead has been on air, its producers have been forced to come up with endless synonyms for the “remix” to keep comic-reading fans from getting bored. In Season 6, fans were worried about Glenn—the character Yeun made a fan favorite, who died around that time in the comics’ story—but Gimple promised a “hard left turn” from his source material. That vow would later seem cynical when Glenn got his skull bashed in anyway.

In truth, however, the cynicism in the show’s writing had begun to show much earlier than that. One could say it was there from the very beginning, as the series seemed to kill off a seemingly endless stream of Black actors whose white peers often seemed to emerge unscathed. One could say it started around Season 2, when fans spent almost a full season bored out of our minds waiting for Rick Grimes and the gang to find a little girl named Sophia—only to find her zombified in a barn.

And one could say it became exceedingly obvious in Season 5, when we spent half a season trying to find Beth Greene—whose rescue went awry at the very last minute in excruciatingly stupid fashion and ended with Beth getting shot in the head. An episode later, when the show killed off another popular character, Tyreese, was the moment this longtime fan finally got bored with the show’s deadly game of musical chairs.

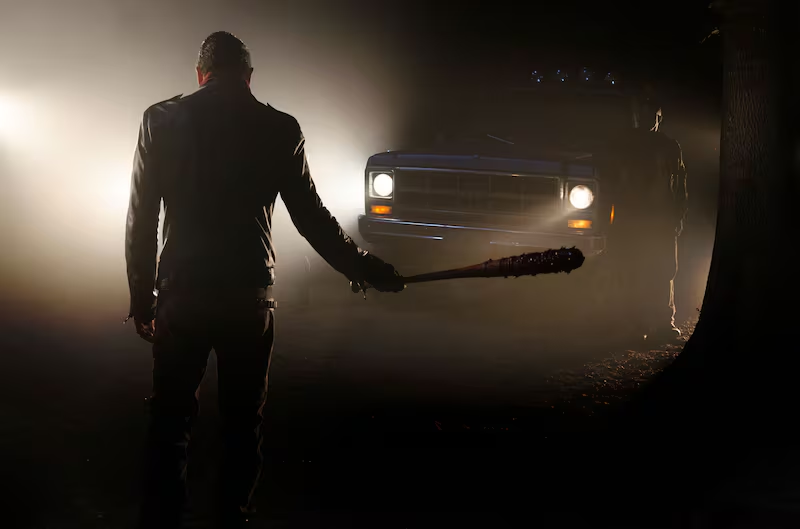

Jeffrey Dean Morgan as Negan in The Walking Dead, Season 7, Episode 1.

Gene Page/AMCBut it was that moment in the Season 7 premiere, when Negan brutalized Steven Yeun’s Glenn Rhee and Michael Cudlitz’s Abraham Ford with a baseball bat after a season of build-up, that seemed to cannibalize the goodwill many fans had for the series in record time.

It didn’t help that most fans expected the scene to happen during The Walking Dead’s Season 6 finale. Instead, after a season’s worth of teasing, the show punted the gory scene to the next year—a forced cliffhanger that seemed to signal that the show did not trust its fans to show up without a guarantee of blood sacrifice. There was also the fact that Gimple had promised (though with careful wording) that the events of the comics (that is, Negan killing Glenn) would not happen exactly as they originally had. This did not turn out to mean Glenn was safe; instead, he died alongside Abraham—a character whose own death had already been delayed by burying a gay character instead.

Season 6 itself had already tricked viewers into thinking Glenn died before his time; early in the season, fans spent weeks thinking Glenn had been ravaged by zombies when in fact, the show eventually revealed he’d hidden under a dumpster. That tease, combined with his death in spite of the “hard left turn” promise, seemed to demonstrate at least a slightly sadistic streak on the part of the writer’s room.

To top it all off, the manner in which Glenn and Abraham died on screen was genuinely grotesque—as in, the scene included a shot of Abraham’s concave skull and a prolonged look at Glenn’s eye popping out after repeated beatings. Even diehard fans found themselves repulsed; some went so far as to complain to the FCC.

The Walking Dead was never a critical darling, but its reputation nonetheless took an indisputable nosedive post-Glenn-gate. The show now feels like a shambolic shadow of its old self—a gruesome game in which new characters stick around just long enough to form an emotional attachment with the audience before they’re summarily executed. (There are too few originals still alive to kill any more of them.) Negan’s gotten a bit more interesting ever since the show decided to let him have some shred of a soul (largely through his relationship with Rick’s spunky daughter, Judith “Ass Kicker” Grimes), but the memory of the cartoonish baddie he once was still lingers. The deaths in more recent seasons have felt less impactful, and its plots more forced.

The slow real-life death of The Walking Dead has, at times, been exaggerated. The show’s viewership has dropped precipitously, but that’s true for all series on cable—in which TWD remains a dominant ratings force. Still, it’s hard not to look at a drop from 17 to 2.2 million same-day premiere viewers in five years, and the show’s gradual retreat from the center of pop-culture attention, without recognizing that its glory days are well behind us.

Even now, however, the show’s producers are not about to let their golden goose die; the franchise now has six spin-off series, four of which are on their way in the next two years. Some fans worry the powers that be will cannibalize all the dramatic moments that could give the finale closure, saving them instead as fodder for these offshoots. They have every right to suspect as much, because time and time again, that’s how this franchise has operated—right down to the forced cliffhanger that ended its heyday.

In the early days of The Walking Dead, it was hard not to wonder how it would end. (Especially after the CDC literally exploded.) The longer the series endured, and the more deaths that piled up, the harder it became to imagine what kind of ending could provide even a sliver of insight into what it all “meant.” If one thing’s been proven, however, it’s that anyone who kills off Steven Yeun does so at their peril.